/ Blog

December 22, 2022

Tunneling Into History: The Amy Street Steam Heating Plant

When the weather outside is frightful, turning up the heat inside can be so delightful! For over 65 years, hundreds of Winnipeggers were kept warm thanks to the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant. Constructed as a backup source of electricity, it was also used to keep many buildings downtown nice and toasty. Although the plant was demolished over 20 years ago, the tunnels it left behind have been an endless source of mystery and intrigue. Is there any truth to the stories of secret passages running beneath Winnipeg’s streets or is it all just a lot of hot air?

On May 10th, 1922, a “cyclone” wreaked havoc north east of Winnipeg, just east of Beausejour. Today we would call this weather event a tornado, as cyclones are defined as tropical storms that develop over the ocean – not really conditions found in southern Manitoba! The storm struck at 12:45 pm and lasted for ten minutes, destroying buildings and infrastructure while injuring several people. Most notably, the storm blew down 34 transmission towers that brought electricity to Winnipeg, cutting off all power and bringing the city to a complete standstill for two hours. The Winnipeg Electric Company, operators of Winnipeg’s streetcars, quickly fired up their auxiliary steam plant to deliver power to customers until their lines were repaired. But for the many served by the City of Winnipeg Hydro Electric System, which lost 22 transmission towers in the storm, it was nearly 24 hours without power, waiting for a temporary line to be built to bring power to the city.

“Suddenly a great black funnel-shaped cloud appeared in the sky and almost simultaneously the mighty wind smote the district. In ten minutes the storm had passed, leaving in its trail wrecked dwelling houses and barns and shattered towers of the electrical power systems of Winnipeg.” Manitoba Free Press – May 11, 1922, page 1

In the aftermath of the event, it was decided that Winnipeg Hydro should also have a standby plant, a backup source of power for the streetlights, waterworks system, essential services and commercial customers, ready for when the transmission lines went down. Winnipeg Hydro approached the city to purchase half of Victoria Park at the end of Rupert Avenue in the Exchange District, wanting the land to build its new plant. Located at the heart of the city since 1883, Victoria Park served as “breathing space” for the working class, the centre for labor activities including the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, a rallying point for parades, a site of athletic contests and concerts, while also being used by the police and military. Small to begin with, the bustling park had already lost some of its real estate to the 1906 James Avenue Pumping Station, so it was not surprising that the community saw the further loss as “criminal.”

Crowds gather at Victoria Park during the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike.

Source: City of Winnipeg Archives

Despite strong public opposition to the location and the offer of several other properties by private individuals, city council thought Victoria Park would be an ideal, both cheap and convenient, especially if the standby plant was coupled with a central steam heating plant. Steam heating plants were a growing trend in the 1920s, and was seen as a way to help offset the high cost of the new standby plant in Winnipeg. Disregarding outcry from the public, on February 19th, 1923, city council approved Victoria Park as the location for Winnipeg Hydro’s standby plant without a single objection. Though only half the park was initially purchased, the second half was bought by Winnipeg Hydro in 1924, replaced by the city with Norquay Park (now Michaelle Jean Park), further north along the Red River on Beaconsfield Street.

Once the location was secured, no time was wasted in building the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant. Under the direction of Winnipeg Hydro’s manager John Glassco, from sod turning to opening banquet took only 13 months, proclaimed to be the “greatest plant in the world of its kind” when it opened on June 18th, 1924 with a capacity of 10 megawatts. Glassco was an electric enthusiast, even using an electric car – which made him seem ahead of his time until you realized the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant was a coal burning plant, replacing a vibrant green space with smoke stacks. Despite this, he hailed the steam plant as a cheap, clean and efficient means of heating a city, which should be embraced as a standard public utility, just like electricity. Despite upgrades to the plant in 1953 and 1954 that brought its total capacity to 50 megawatts, steam was never the utility of the future Glassco purported it to be. The plant could have been converted to gas in the 1960s, but continued burning coal, becoming poorly maintained and a heavy polluter.

The Prince of Wales visiting the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant in 1927.

Source: Archives of Manitoba (The Year Past 1990)

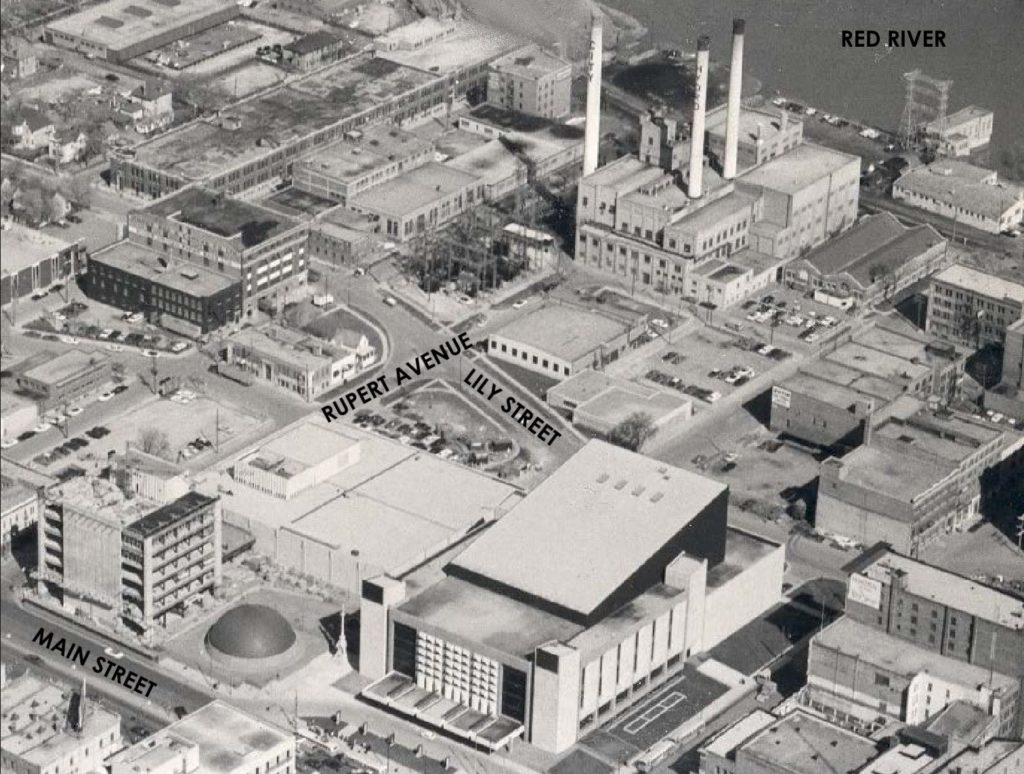

Costing approximately $1.9 million to build, the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant was an industrial interpretation of Art Deco architecture. A robust brick building, it emphasized the smooth cubes, hard edges and geometric ornamentation of the modern, jazz-age style. Above the building would eventually tower three great smoke stacks, becoming a landmark in the Exchange District for many years. Beyond the bounds of the building extended a network of underground pipes, used to transport the steam to buildings throughout the downtown. It heated Winnipeg’s City Hall and Administration Building, the demolished Public Safety Building, the Manitoba Museum, the Centennial Concert Hall, the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, Metropolitan Entertainment Centre, Union Bank Building and Birt’s Saddlery to name a few.

The tunnels dug to accommodate these pipes have become part of Winnipeg’s lore, with rumors of secret passages downtown being used for all kinds of nefarious activities. While there are actually tunnels under the city, the stories that rise up from them might be a bit exaggerated! Tunnels under the Manitoba Legislative Building were supposedly installed so politicians could escape should an angry mob descend on the building. The tunnels are really there, but they are used to supply heat from the Central Power House at 219 Memorial Boulevard, which is also connected to the Vaughan Street Jail, the Winnipeg Civic Auditorium, the Norquay Building, the Woodsworth Building, the Old Law Courts Building and more. And as soon as you have tunnels connected to a jail, you have stories of daring escapes, which may or may not be true. Today, these tunnels are still used by the Central Power House system – keeping Winnipeg warm for 107 years!

A tunnel at the Manitoba Legislative Building under construction on October 14th, 1916.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

Along with tunnels for the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant – tunnels probably being a generous description for the spaces housing pipes – there were also hollows under the sidewalks in the Exchange District. These tunnels provided extra space for the warehouses and in some rare cases, allowed goods to be moved between buildings without going outside, like the tunnel between the Great West Saddlery Building and the Great West Saddlery Warehouse (closed in the late 1980s). The tunnel under what was once the Bijou Theatre also held several jail cells, left over from when the building above was Manitoba’s courthouse, jail and part-time legislature. Today only one sidewalk tunnels remains, located in front of the Woodbine Hotel, it is used for beer deliveries. The last time one of the subterranean jail cells was seen was in the 1970s, before the Bijou Theatre burned down in 1979. It is also rumored that these tunnels in the Exchange District were used by bootleggers to smuggle alcohol during Prohibition, which lasted from 1916 to 1923. Cheers, anyone?

A mythical tunnel was said to have connected Winnipeg’s gingerbread City Hall (demolished in 1962) and the Leland Hotel at 218 William Avenue (lost to a suspicious fire in 1999), used by city councillors to visit their mistresses at the hotel during the lunch hour. If someone tells you this story, know that they are just blowing smoke! Finally, there is supposedly a haunted tunnel connecting the steam plant at the Forks (now CityTV) to Union Station, the Manitoba Club and the Fort Garry Hotel. Was it used for heating? Transporting laundry? Carting luggage? Sneaking people into the Manitoba Club? Urban legends claim the tunnel housed a barber shop, restaurant and tailor, and is haunted by someone that died there. Those more familiar with the buildings say the tunnel never existed, it was just a trench for a heating pipe, which collapsed over 35 years ago. There was a tunnel connecting a train station and hotel in Winnipeg – only it was the Canadian Pacific Railway Station and the Royal Alexandra Hotel (demolished in 1971) on Higgins Avenue. Perhaps someone’s story got a little hazy over time?

The Royal Alexandra Hotel (left) and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station (right) on Higgins Avenue were connected by a tunnel.

Source: Winnipeg Public Library PastForward

At its peak, the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant kept about 700 customers warm during Winnipeg’s frosty winters. But by the end of the 1950s, buildings began to disconnect from the steam plant, installing their own gas heating systems, which were far more affordable over time. Maintaining underground pipes carrying steam and upgrading the plant were costly, with only older properties in the Exchange District connected to the steam plant during its final years. Due to rising costs and new pollution regulations, the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant was closed in June 1990, with the final 100+ customers taken offline, leaving 4.3 million square feet of buildings without heat. It then cost another $4 million to abate the asbestos from the building. Interestingly, the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant was never once used for emergency power – the main reason it was originally built!

Amy Street Steam Heating Plant with it three smoke stacks towering over the East Exchange District, with the James Avenue Pumping Station to the right, circa 1974.

Source: City of Winnipeg (City of Winnipeg Report)

A year and a half after the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant closed, about 35 buildings in the Exchange District were still left out in the cold. For building owners already struggling to make ends meet, spending tens of thousands of dollars on a new heating system was impossible. Although the heritage community agreed the plant needed to close, it was a real setback for the built heritage of Winnipeg’s Exchange District, causing necessary vacancies and decay instead of revitalization.

Over time, there were a variety of proposals for what to do with the defunct Amy Street Steam Heating Plant. In 1976 a study was done on the feasibility of burning the city’s garbage at the plant to produce hot water that could then be used to heat buildings. In 1990, Unitel Communications of Toronto offered to purchase 13,320 metres of pipes along with 120 manholes, once used to carry steam from the plant to customers, they could instead be used to run communication lines. Then, in 1999, there was a grand plan to spend $49.5 million converting the building into a film studio. While the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant was once on the city’s inventory of historical buildings, all of these plans vaporized and the building was eventually demolished in 2001, replaced with condominiums.

Other than the tunnels hidden under our feet, the only thing left from the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant is the Amy Street Pump House, built in 1951 to provide water for the plant. This little brick building did not suffer the same fate as the plant, being adaptively reused instead of demolished, first as the city’s Harbourmaster Building used by the Winnipeg Police River Patrol and later becoming the trendy Cibo Waterfront Cafe. While the Amy Street Steam Heating Plant has vanished into thin air, people still go full steam ahead searching dark corners in the basements of Winnipeg’s heritage buildings, hoping to uncover a hidden entrance to our city’s buried past!

❄️ Stay warm and HAPPY HOLIDAYS from EVERYONE AT HERITAGE WINNIPEG! ❄️

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

333 Waterfront Drive - Harbour Master Hotel | Christian Cassidy - Winnipeg Places - October 12, 2011

1990: The Year Past | City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings Committee

The Amy St Steam Plant: Winnipeg’s Era of Steam Heat | George Siamandas - The Winnipeg Time Machine

Architectural Styles | Heritage Manitoba

The beast is coming down: Demolition of ugly steam plant will open window to Main Street | David O’Brien - Winnipeg Free Press - December 5, 2002, page 1

Closing steams owner: core area businesses irked by costs to switch from steam heat to gas | Nick Martin - Winnipeg Free Press - December 17, 1989, page 3

Communication firm eyes city’s steam pipe network | Aldo Santin - Winnipeg Free Press - November 19, 1990, page 3

Cyclone Damages Power Plants and Wrecks Building East of Winnipeg: Electric Utilities Suddenly Crippled | Manitoba Free Press - May 11, 1922, page 1

Cyclone Damages Power Plants and Wrecks Building East of Winnipeg: Fearful Havoc in Lydiatt and Sinnot | Manitoba Free Press - May 11, 1922, page 1

Cyclone Damages Power Plants and Wrecks Building East of Winnipeg: Summary of Damage Done By Yesterday’s Big Storm | Manitoba Free Press - May 11, 1922, page 1

Cyclone Vs. Tornado | ScienceStruck

Garbage could heat the Civic Centre | Debbie Sproat - Winnipeg Free Press - October 28, 1976

Historic buildings sit as ‘ghosts in the urban landscape’ following steam plant shut-down | Teresa Crellin - Winnipeg Free Press - December 3, 1991, page 131

A History of Electric Power in Manitoba | Manitoba Hydro

Hydro System City’s Greatest Resource: Mighty Power Plants On Winnipeg River Serbe Vast District | J.G. Glassco - Winnipeg Evening Tribune - November 13, 1923, page 6

Manitoba Hydro - Facebook - June 22, 2020

New light shed on tunnels | Bruce Owen - Winnipeg Free Press - October 18, 2012

A surfeit of movie studios | Nicholas Hirst - Winnipeg Free Press - September 25, 1999, page 19

Timeline of Winnipeg Historical Events 1670-2012 | City of Winnipeg - May 20, 2021

Winnipeg eyes $40M waterfront development | CBC News - July 9, 2008