/ Blog

August 19, 2020

This is the House that Bawlf Built: 11 Kennedy Street

On the prairies, in a city, on a street, at the corner, once stood the house that Nicolas Bawlf built. A mansion in the style of a queen, the house was built for the king of Winnipeg’s grain exchange. Standing proudly on a street steeped with history, the beautiful home did not even last 100 years. It was a castle that no knight in shining armor was able to save. But it is an important story that deserves to be told, to remind us of what has been lost and to take better care of our precious heritage treasures that remain!

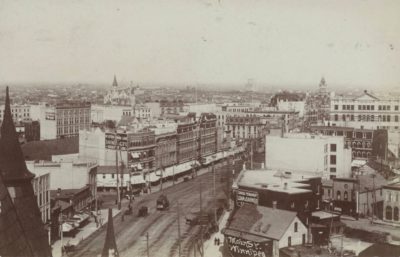

By the end of the 19th century, the young City of Winnipeg was in good form. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) surrendered its land in 1870, paving the way for the creation of the Province of Manitoba in 1870. This was followed by the incorporation of the City of Winnipeg in 1873. The transcontinental railway had arrived, the initial real estate boom and bust had passed, the economy was being bolstered by the flourishing grain trade and growing warehouse district, while people were flooding in from all over the world. What was once dirt roads and small wooden buildings had become a bona fide modern city.

Main Street in Winnipeg, looking north from the roof of the Manitoba Hotel (where the Federal Building now stands) at the end of the 19th century.

Source: PastForward

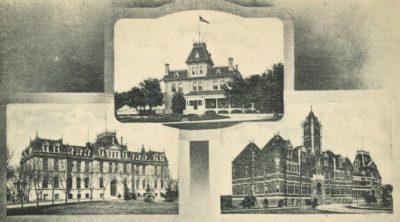

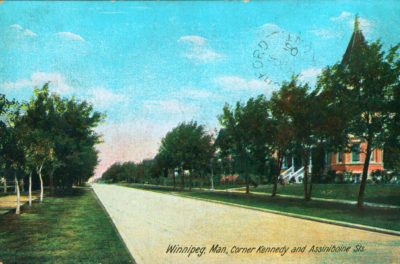

Kennedy Street, named after Winnipeg mayor William Kennedy, was a 1.7 kilometre stretch of road running south from Cumberland Avenue down to the Assiniboine River. It seems to have attracted a particularly large number of grand buildings, although most were built in the early 20th century. A large parcel of land in the southwest corner, running along the west side of Kennedy Street, became the home of the provincial government. The Government erected three splendid buildings, Government House (1882), the Manitoba Legislative Building (1884) and the Court House (1882).

The Manitoba Legislative Building (left), Government House (center) and the Court House (right) were all located on Kennedy Street at the end of the 19th century.

Source: PastForward

The presence of these palatial government buildings no doubt made the real estate on the east side of Kennedy Street a valuable commodity. So it is not surprising that in 1897, Nicholas Bawlf, a wealthy grain merchant, set about building his own castle at the corner of Kennedy Street and Assiniboine Avenue. Born in Ontario in 1849, Bawlf married Katherine (Catherine) Madden in 1877 and together they had nine children, three daughters and six sons. Bawlf made his fortune from grain and was one of the founders of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange. He also dabbled in politics, serving on the Winnipeg School Board and as City Alderman for a single year (1883-1884). By the turn of the century, Bawlf had become one of 19 millionaires in Winnipeg, so undoubtedly no expense was spared when he built his new home at 11 Kennedy Street.

Bawlf’s new house was designed by Samuel Hooper, a prolific Englishman who went on to become Manitoba’s Provincial Architect in 1904. Originally trained in stone carving and monument design, Bawlf’s house seems to have only been Samuel’s fifth foray into architecture. Construction of the house cost around $12,000, which would be about $350,000 in 2020. P. Burnett served as the mason and J.A. Girvin as the carpenter.

The 1886 Volunteer Monument is the first work credited to Samuel Hooper. It originally stood in front of Winnipeg’s City Hall, commemorating those of the 90th Winnipeg Battalion killed in various battles.

Source: PastForward

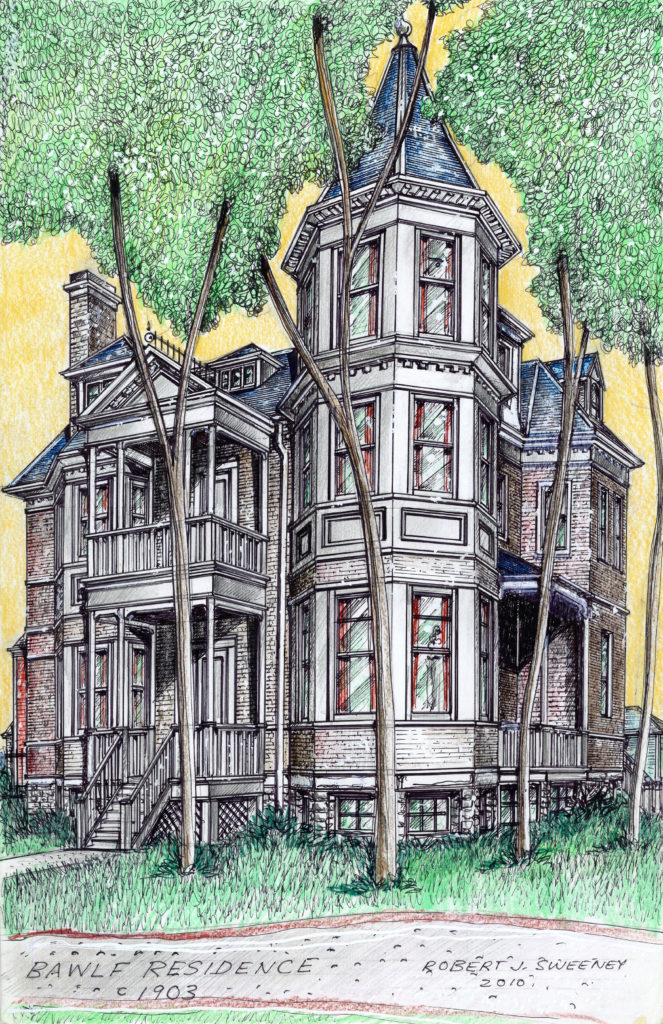

Interestingly, Bawlf’s house seems to have been Hooper’s only use of the Queen Anne Revival style of architecture. It is the style most closely associated with the Victorian era, although it only rose to popularity in Canada during the last decade of Queen Victoria’s rule. Today such homes are often referred to as “painted ladies” because they are brightly coloured and draped in lacy woodwork.

At the corner of Kennedy Street and Assiniboine Avenue, the location of Bawlf’s new home was perfect for displaying Queen Anne Revival architecture, providing two facades to advertise his wealth to the public. A buff brick facade was set atop a rough-cut stone foundation, further accented with horizontal bands of rough-cut stone, decorative brickwork and dentil cornices. A two-story bow window on the west facade and a two-story bay window on the south facade were bridged by what appears to be an octagonal tower looking out over the intersection. The west facade also featured a two-storey porch supported by columns and topped with a front-facing gable, which served as a grand entrance to the house. A single-storey version of the porch without steps was placed on the south facade of the house, which provided some balance in the house’s appearance, although symmetrical it was certainly not. The top level of the two and a half storey home would have provided an interesting space, with all manner of dormers and roof lines. This level of the tower appears to have been clad in something other than buff brick, which is not surprising as all types of decorative wooden shingles were used in Queen Anne Revival architecture. The roof of the tower rose high above that of the rest of the roof, topped with a finial, the finishing touch on an opulent home.

The interior of Bawlf’s home at 11 Kennedy Street was not less magnificent than the exterior. The finest materials and highest quality craftsmanship were used to ensure no space was without decoration. From the multiple stained glass windows to the extremely detailed woodwork, the interior of Bawlf’s house was luxury at its finest.

Glorious stained glass at the entrance, the sidelights and transom showing urns overflowing with greenery and flowers, the sunset catching every leaded petal. Golden oak panelling marched up the square staircase. Double round arches supported slender oak pillars. Plaster ornamented ceilings revealed cherubs sporting amid garlands and even torches. The bronze lamps with amber glass carried on the mellow tones.

Source: Winnipeg in Focus

It would appear that Bawlf was pleased with the design of his house, as he then hired Hooper to design the Grain Exchange Building at 156-160 Princess Street in 1898. This was a departure for Bawlf, who had used architect Charles Arnold Barber for is previous two buildings, the 1882 Bawlf Block at 150 Princes Street and the 1892 Bawlf Grain Exchange II at 164 Princess Street. While the two Exchange buildings were both used for the grain trade which Bawlf was heavily involved in, the Bawlf Block was more of an investment property, rented out as commercial office space. In 2003 all of Bawlf’s buildings on Princess Street were demolished except for their facades, which were saved, restored and beautifully integrated into Red River College’s downtown campus. The excellence in saving the historic facades was recognized by Heritage Winnipeg with a Heritage Conservation Award at the 2004 Annual Preservation Awards.

After construction of the house at 11 Kennedy Street was complete, a number of tragedies befell the Bawlf family in the first part of the 20th century. First, Bawlf himself suddenly passed away from a heart attack on Boxing Day in 1914. This caused the remainder of the family to move out of the grand house. World War I saw four of their sons to enlist and one, Sub-Flight Lieutenant David Leland Bawlf (known as Barney) became of causality of war on April 21, 1918, in Pas-de-Calais, France. The third and final tragedy for the family came only seven months after the death of Barney. Bawlf’s wife, Katherine, passed away on November 26, 1918, in Los Angeles, California.

The elder sons carried on their father’s legacy until the stock market crash of 1929. Due to the Great Depression, the Bawlf wealth almost disappeared overnight. The Bawlf Grain Exchange II was repossessed by the City of Winnipeg for back taxes. But the Bawlf’s legacy lives on with the village of Bawlf, Alberta, which was named after the family. Many of Bawlf’s extended family members also served in the Canadian Forces, including Lieutenant William Fredrick Bawlf, Bawlf’s grandson, who became a causality of the Second World War.

After the Bawlf’s, 11 Kennedy Street had numerous residents, though none that stayed for very long. This appears to be a re-occurring theme for these grand old homes. It is likely due to the size of the homes and the cost of upkeep. The second resident of 11 Kennedy Street was a Samuel H. Montgomery, who lived there in 1916. The third resident was the Archbishop of Winnipeg, Alfred Arthur Sinnott, who lived in the home from late 1916-1918. As the first Archbishop of Winnipeg, he served the Roman Catholic churches of the city from 1916-1952.

In 1919, a member of the Bawlf family returned to the home at 11 Kennedy Street. Bawlf’s youngest daughter, Kathleen Esther Bawlf, married Geoffrey Cameron Griffin on January 7, 1919. Together they moved into Kathleen’s childhood home for roughly a year. Findlay W. A. Young then briefly lived in the house from 1920-1921. He was involved with the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad (GTPR) and served in provincial politics. His allegiance was to the Liberal Party and he served as Speaker in 1895. He was friends with Nicholas Bawlf due to the important role the railway played in transporting grain. He also ran in the same social circles as William P. Hinton of 604 Stradbrook Avenue, due to his investments in the GTPR.

Next 11 Kennedy Street was adapted to be reused as the Machon Academy of Arts from September 1921 till mid-1923. The house was divided up into studios and artists of all disciplines were invited to rent a space. Most of the studios were rented to musicians, who used the space to teach. The most common instrument taught appears to be the pianoforte or piano. There is no indication of what happened to the Machon Academy. The woman who ran it, Mme. Morgan Machon, disappeared from public record in mid-1923.

From October 1923 until 1929, 11 Kennedy Street was the headquarters of Toc H. Toc H is a Christian organization that promotes acts of kindness and community involvement. It was founded during World War I as a social gathering place for British soldiers. The headquarters in Winnipeg was a fraternal organization but it did not have any formal connection with a post-secondary school. The fraternity officially opened in November 1923 and lived up to its values. The papers of the time frequently reported on their charitable and community deeds. They installed a stained glass window over the main entrance stating “Abandon rank all ye who enter here”, which later became a defining characteristic of the home.

Wasyl Swystun (Василь Свистун) was the next resident of 11 Kennedy Street, he lived there approximately two years from 1930-1932. Swystun was a lawyer and an exceptionally well-known member of the Ukrainian-Canadian community in Winnipeg. He was also quite the singer and served as choral-master for the Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Mary the Protectress for many years. Swystun spoke at an event on January 3, 1938, that attracted over 700 people, including Mrs. John Bracken and her son Bruce Bracken, who had once lived at 604 Stradbrook Avenue.

The P. Moyhla Ukrainian Institute was next in to take up residence at 11 Kennedy Street. Officially known as the St. Petro Mohyla Institute but often shortened to the Mohyla Institute, it is a Ukrainian-Canadian Student residence. It promoted Ukrainian culture and offered lessons in Ukrainian language and culture, while also serving as a hub for the Ukrainian-Canadian community. The home appears to have been gifted from Wasyl Swystun as he was a former principal of the Mohyla Institute and opened in July 1932. Mohyla Institute closed its doors in Winnipeg in the summer of 1933 for economic reasons. The Mohyla Institute still exists in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan as a residence and community hub.

Once the Mohyla Institute moved out, the home became a single room occupancy (SRO), more commonly known as a boarding house. The first advertisement was in the Winnipeg Free Press was on November 10, 1933. A majority of the advertisements are for simply for a room, as bathrooms and the common area would have been shared. SROs were a common type of housing as they were very affordable at a time when many people were struggling due to the Great Depression. At this time, a widow would often live in such a home to serve as a supervisor of sorts and cook meals for those that wished to pay for that option. This is possibly why Mrs. Elizabeth Martin is listed as owning the home in 1934 and 1935. Mrs. A. Hohtanz appears to have done the same from 1937-1939. The house had 19 suites in 1939 but that number was reduced over time to 14 suites in 1965. In 1972, it was called the Jasmin Apartments, or, “The Castle” by those that lived there. Featuring rough-cut stone and an imposing tower, it is easy to see why the house earned this nickname!

1976 was the final year of life for the grand house at 11 Kennedy Street. The house was no longer compliant with fire codes and to upgrade it would have taken a significant sum of money. The owner, Ashley Brown, was going to demolish it but there was an outcry from the tenants. The tenants and the University of Winnipeg’s Institute for Urban Studies persuaded Brown to spend $5000 to help bring the house up to code. They went to the city and proposed some alternate solutions, such as smoke detectors instead of heat detectors. The City agreed with them partially and even removed the requirement for a second exterior fire escape. But the City required all the smoke detectors to be wired together, which would have been extremely costly in a house that large. This proved to be too much for Brown and he went forward with demolishing it, much to many peoples’ chagrin. It is possible if Brown was willing to appeal the decision that the 79-year-old home could have been saved? The house was torn down Monday, November 15, 1976.

Had 11 Kennedy Street been able to hold out for another couple of months, it might have benefited from the protection of Winnipeg’s first Historical Buildings By-law, passed on February 2, 1977. It was enacted in a response to citizens taking to the streets, angered over the flippant destruction of Winnipeg’s historic buildings that was rampant in the 1960s and 1970s. Unfortunately, Winnipeg’s mayor from 1960 to 1977, Stephen Juba, seems to have been a major proponent of this movement, overseeing the demolition of many historic buildings.

Today, the Riverwalk Apartments stand at the corner of Kennedy Street and Assiniboine Avenue, its soulless facade casting a long shadow on the once charming neighbourhood. As of 2020, only four historic buildings remained on Bawlf’s block of Kennedy Street: Government House, the 1912 Reid House, the 1928 Willingdon Apartments at 75 Kennedy Steet and the 1905 Rideau Hall at 85 Kennedy Street. None of these buildings have any sort of heritage protection and could at any time be replaced at any time by more bland apartment buildings, which are already popular on the street. It is extremely sad to see a home like 11 Kennedy Street demolished over a relatively uncomplicated matter, especially when the house had so much more life left to live. Unfortunately, there is no time machine to undo the past, but we can celebrate these homes with memories, and use those memories to inspire us to help conserve Winnipeg’s remaining built heritage before it is all disappears.

An original print of Bawlf Residence in 1903 by Robert Sweeney. You can purchase this print in the Heritage Winnipeg store!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Rheanna Costen and staff on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Advertisement | Winnipeg Free Press - November 29, 1922, Page 27.

Architectural Styles | Heritage Manitoba

"'Barney' Bawlf Killed" | Winnipeg Free Press - April 25, 1918, Page 8.

Bawlf House | Winnipeg Building Index - University of Manitoba Libraries.

Bawlf, Nicholas | Dictionary of Canadian Biography

"cosmopolitan" | Merriam-Webster

"Historic Winnipeg" | Winnipeg Free Press - March 5, 1983, Page 48.

History in Winnipeg Streets | Manitoba Historical Society

Hooper, Samuel | Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950

Item i01633 | City of Winnipeg Archives

Katherine Madden Bawlf | Manitoba Historical Society

Manitoba Legislative Building | Manitoba Historical Society

"Nicholas Bawlf, Notable Citizen, Dies Suddenly" | Winnipeg Tribune - December 28, 1914, Page 9.

Page 1 | Winnipeg Tribune - February 14, 1895.

Page 118 | Winnipeg Free Press, November 17, 1976.

"Part IV - The Archdiocese Of Winnipeg, 1916-1952" | Archdiocese of Winnipeg

PC 18/7190/18-6237-032 | Jim Walker - Winnipeg Tribune Photo Collection -

"A Prince Takes Centre of the Stage" | Winnipeg Tribune - January 3, 1938, Page 8.

"Prizes Distribution For Toc H Carnival" | Winnipeg Free Press - October 29, 1924, Page 5.

The Queen Anne Revival Style | Canada's Historic Places

Queen Anne Revival Style (1870 - 1910) | Ontario Architecture

Reportorial Round | Winnipeg Tribune - June 29, 1897, Page 5.

Samuel Hooper (1851-1911) | Manitoba Historical Society

Second Empire (1860 - 1900) | Ontario Archutecture

Second Empire Architecture | Canada's Historic Places

Social and Personal | Winnipeg Free Press - January 9. 1919, Page 8.

Society's Realm | Winnipeg Tribune - October 29, 1898, Page 6.

"Some Old Winnipeg Buildings" | Randy Rostecki - Manitoba Historical Society

"Stories Houses Tell" | Lillian Gibbons - Winnipeg Tribune - February 20, 1937, Page 16.

"Tentants' Bid to Save 79-Year-Old House Fails" | Winnipeg Free Press - September 24, 1976, Page 70.

"Thirty Years Ago Today - 1883" | Winnipeg Free Press - January 4, 1913, Page 1.

To Let | Winnipeg Free Press - September 10, 1921, Page 24.

"Ukrainian Teachers Hear Swystun Talk on Causes of Depression"| Winnipeg Free Press - July 16, 1932, Page 13.

Unfurnished Rooms | Winnipeg Free Press - November 10, 1933, Page 22.

Utility Building | Canada's Historic Places

The Volunteer Monument | Manitoba Historical Society

"Wasyl Swystun" | Winnipeg Free Press - December 28, 1964, Page 29.

The Western Canadian Fire Underwriters' Association

"Winnipeg - Canada" | City Council

Winnipeg's Fammous Homes | Manitoba Historical Society

Winnipeg Residences | Winnipeg Now and Then

"Winnipeg's Home of Toc H Opened" | Winnipeg Tribune - November 13, 1923, Page 2.

Very interesting article, excellent research. Very sad that the house probably could’ve been saved. Keep up the great work!