/ Blog

May 19, 2021

Dragons in Winnipeg: The Mandarin Building

The architecture firm of Barber & Barber is likely best known for designing Winnipeg’s elaborate “Gingerbread” City Hall in 1884, though the family-run firm completed a number of other projects in Winnipeg from schools, private homes, and other public buildings. Among their myriad of Winnipeg works was Winnipeg Police Court at 223 James Street, built in 1883.

Now named the Mandarin Building, it bears many of Barber’s trademark architectural flourishes. The company was run by Charles and Earl Barber, brothers, with little to no architectural schooling. Charles the eldest brother, claimed to have apprenticed in Rome, and at a New York architecture firm for five years but otherwise there was no formal training. As a practicing firm, Barber & Barber preferred highly eclectic and ornamental designs, borrowing from a variety of styles to create grandiose structures.

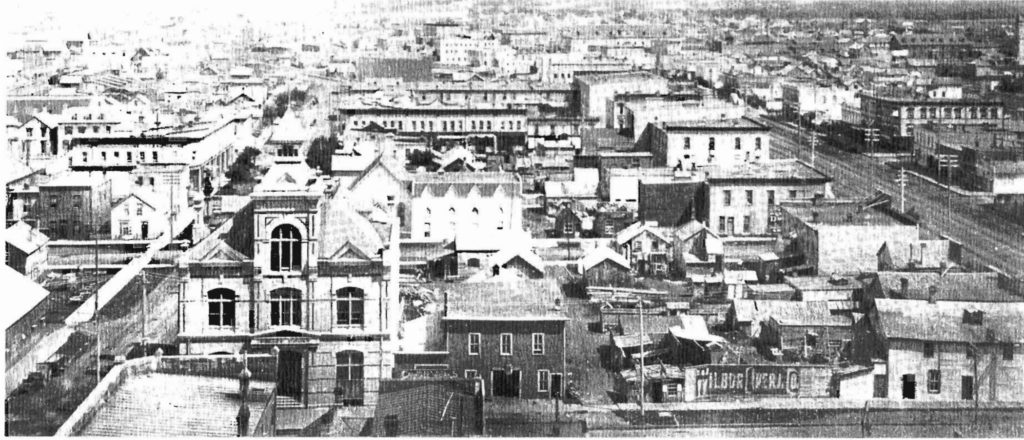

A view from City Hall in 1895, with 223 James Avenue in the bottom left corner.

Source: City of Winnipeg Historic Buildings Committee Report, 1983.

Originally the neoclassical-inspired building provided 18 jail cells on main floor, next to a large courtroom. There were court offices on the second floor, as well as an attic dormitory for several of the 15 men who worked on the police force in 1883. For the criminal who wound up in the police court cells, there was always the possibility of escape. The bars of the cells were made of soft iron, which could be bent, and the locks were easily picked. Most times, on-duty officers caught the escapees before they had fled the building.

Winnipeg’s police force grew in size over the course of the following 20 years. By 1908, there were 115 officers and the Winnipeg Police Court was moved to a new location on Rupert Avenue. The former police court on James Street was adaptively reused as municipal offices, with work done by Architect John D. Atchison. These renovations removed many of the roof details and the central tower, replacing them with simple dormer windows.

As well the community around the building had begun to change by 1908. Further south was the bustling warehouse district, now known as the Exchange District, a hub of Winnipeg industry and wholesale. Less than a block west was the growing neighbourhood of Chinatown. The first recorded Chinese residents in Winnipeg were Charley Yam, Fung Quong and an unnamed woman who came from the United States in 1877. In the following years, more Chinese people came to Winnipeg from the northern United States and set up Chinese laundries, groceries, tobacco shops and rooming houses.

It was the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway that brought hundreds more Chinese immigrants to the prairies during the 1880s and on wards. By 1919, Winnipeg’s Chinatown was the fifth largest in Canada with 900 men and a handful of women. The neighbourhood spanned from a core area at King Street and Alexander Street, framed by Logan and Rupert Avenue and Princess and Main Street.

Few Chinese women were able to immigrate to Canada during the early-mid 20th century; the Canadian government’s immigration policy required Chinese immigrants to pay exorbitant head taxes ($500 per person in 1903). Though husbands, fathers, and sons had moved to Canada for work, poor wages prevented many from paying the head tax required to bring their families over. An act amendment in 1923, essentially excluding all Chinese immigrants, made it impossible for families to move here. Throughout this period, Chinatown was a bustling cultural hub full of commercial and residential activity. The Chinese Nationalist League opened their headquarters in a 1910 office block at 211 Pacific Avenue in 1923. The building was designated a historic building by the city in 2019.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1947, and women and children emigrated to Winnipeg to rejoin their families. Chinatown residents moved elsewhere in the city, and Chinatown began to slowly decline as a result.

A Lion Dance. Members of Winnipeg’s Chinese-Canadian community perform in Chinatown, 1949.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Chinese Historical Society Collection, P7072, 8/3.

After years of stagnation, a revitalization push began in the 1980s, led by Dr. Joseph Du and Philip Lee. Du was a Taiwanese immigrant who worked as a pediatrician from 1961-2002, and was an active member of the Chinese-Canadian community. Du chaired the 50th anniversary celebrations for the repealing of the Canadian exclusion act, and also served as the Director of the St. Boniface General Hospital and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

Lee who emigrated to Winnipeg from Hong Kong to further his education, worked as a research chemist with the City of Winnipeg for many years. He was also a vocal advocate for Winnipeg’s Chinese-Canadian communities.

Du and Lee first worked together in 1970 to plan an event for Manitoba Centennial Celebrations. The duo organized gatherings and flea markets at the Hudson Bay Company store downtown, and called in eight different groups to organize displays. The first Folklorama was held as a part of the Centennial celebrations, with Chinatown offering a street festival with performers from King Street to Pacific Avenue. By the 1980s Du and Lee had nearly a decade of experience working together, when they began to push Mayor Bill Norrie for a major Chinatown revitalization project. The Chinatown Development Corporation, chaired by Du, sought to provide “low income housing, a community centre, job training offices, day-care and general rehabilitation to the area“. In 1987, the $15 million first phase was completed with the construction of the six-storey Dynasty Building, Chinese Gates, and Harmony Mansion Housing Project.

At the time, 223 James Street was the run-down former home of the City of Winnipeg’s Engineering Department. It had briefly been a designated historic structure with the City of Winnipeg on December 5, 1983, but the designation was removed just a few years later on August 20, 1986, likely because it was seen as a hindrance to redevelopment in the area. In fact, the initial redevelopment plan for Chinatown involved demolishing 223 James Street, but Heritage Winnipeg and other advocates pushed back against the decision. There was hope that a compromise could be reached, with an addition instead of demolition. Ultimately, just over a century after it was built, the former Winnipeg Police Court was completely demolished.

In 1989 work began on the Mandarin Building that we see today, with the facade on James Avenue being a replica of the 1883 Winnipeg Police Court building that was demolished. The architecture firm of Smith Carter were behind the project, which included a large addition finished in matching golden buff brick, stretching northward down King Street. An impressive piece of public art is also found on the new addition: a ceramic replica of the Imperial Nine Dragons mural found in Beijing’s Forbidden City.

There are still City of Winnipeg offices inside 223 James Street, but the building is now connected to a larger neighbourhood story of growth, determination, and resilience. In May 2019, CentreVenture announced the “Northwest Exchange Chinatown Strategy”. The goal of the strategy is to “analyze existing conditions in the neighbourhoods and establishes principles for future development with a focus on filling in vacant lots, enhancing the history of the area, creating affordable housing, and supporting local and independent businesses“. The Mandarin Building is located in “Catalyst Zone 2: Chinatown High Street” area of the strategy, where the focus will be on developing a commercial main street with adaptively reused heritage buildings, infill and a revitalized streetscape. Heritage Winnipeg is hopeful that with the meaningful consultation of stakeholders and a firm grounding in best practices, this new strategy will reinvigorate the Mandarin Building and its surroundings, while ensuring a place for the people who already call Chinatown home. It is a wonderful opportunity to celebrating heritage buildings for what they do best: creating diverse, inclusive, unique neighbourhoods, that support a sustainable future and honour our community’s past!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

1982, The Year Past City of Winnipeg Historical Building Committee Report

Architectural Styles, Heritage Manitoba

Barber and Barber, Canadian Encyclopedia

Charles Barber, Dictionary of Canadian Biography

A Conversation with Winnipeg's Chinese Canadian Duet, Alison Marshall (Manitoba Historical Society)

A Development Strategy for Northwest Exchange District and Chinatown, CentreVenture

Mandarin Building, Winnipeg Architecture Foundation

Murray Peterson, City of Winnipeg Heritage Officer

Northwest Exchange Chinatown Strategy Released, CentreVenture

Winnipeg Free Press Files