/ Blog

November 10, 2021

Union Station: A Gateway to Winnipeg’s Past

Winnipeg is full of historic places, from the Exchange District at the heart of the city traversed by the outstanding Bankers’ Row, to the charming century-old neighbourhoods that many call home. There is one historic place in this city, however, with a place in history that has witnessed the birth of a budding city and survived many generations to exist today as a local landmark. Union Station, situated at the end of Broadway at 123 Main Street, stands as a gateway to the Forks and encapsulates a memory of another era.

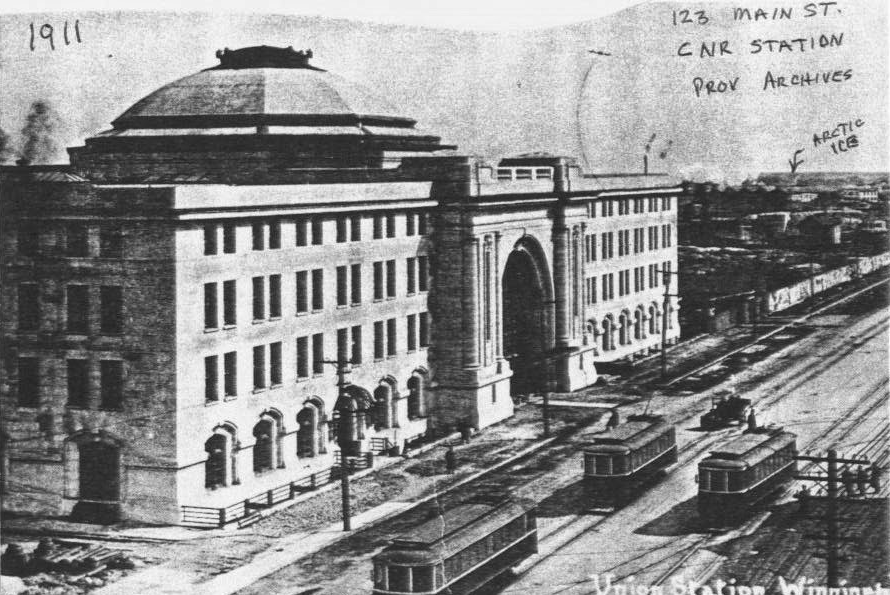

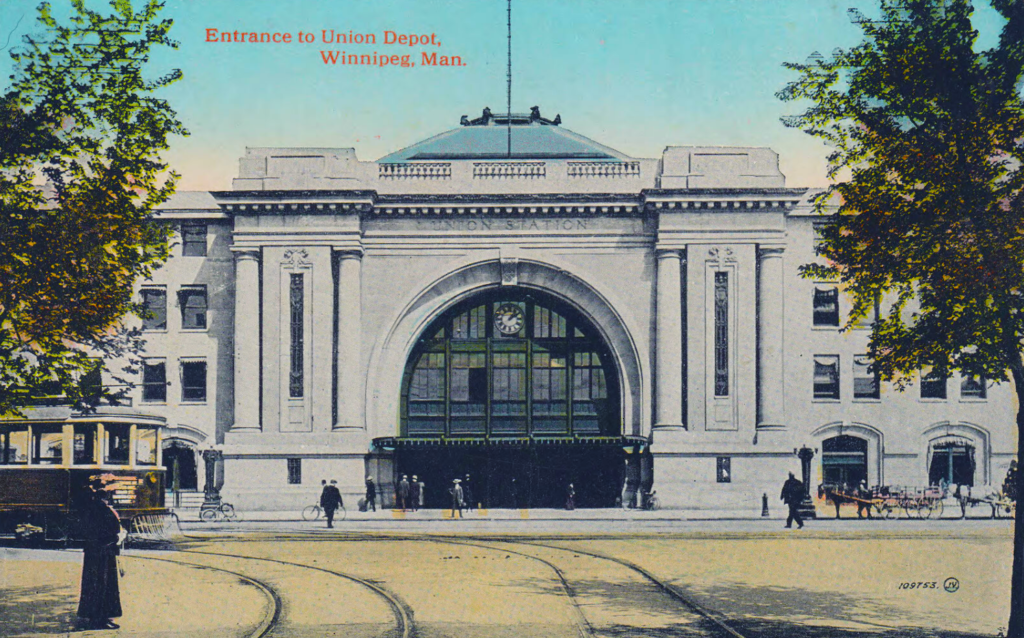

Built from 1908 to 1911, Union Station was designed by New York architects Warren and Wetmore, a major architecture firm most active during the early 1900s with their most notable project being the work on Grand Central Station or Terminal in New York City. Union Station was meant to be essentially a younger sibling of this famous train station. With inspiration directly pulled from it in aspects such as the iron canopy emphasizing the arched entrance, the large columns flanking the front doors, and the expansive high ceiling rotunda that greets you upon entering the building.

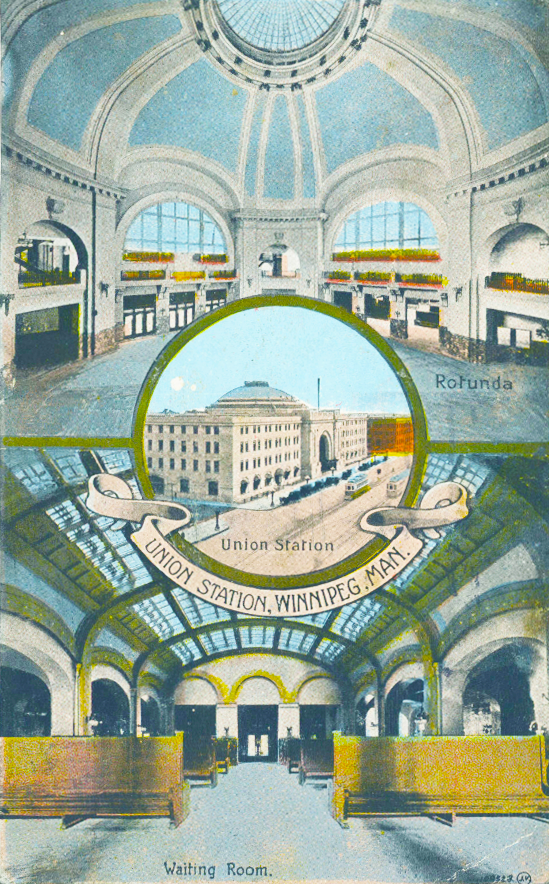

The Beaux-Arts style that the architects worked in to the design of Union Station is quite apparent in the overall aesthetic of the building. The Beaux-Arts architectural style is of French origin and is said to be a branch of the Neoclassical and Greek Revival architectural styles. These types of buildings were known to be placed in populated urban areas where the building would stand out due to its size and grand architectural details. A few characteristics of this style are symmetry on a grand scale, the use of columns, and large exaggerated arches. This style is normally very extravagant in stature and detail, but in comparison, the design of the Union Station is on the muted end of the spectrum on the exterior. Still following in the style, the façade of the building, constructed with local limestone, is almost perfectly symmetrical with an axial plan. The north and south wings have pairs of windows that mirror each other, and each of the ground floor windows has individual detailed arches. The interior features a large domed ceiling that arcs over the entrance space. Details of the Beaux-arts style are further expressed by the wainscoting, planer qualities, intricate roof details, and the stupendous size of the interior environment.

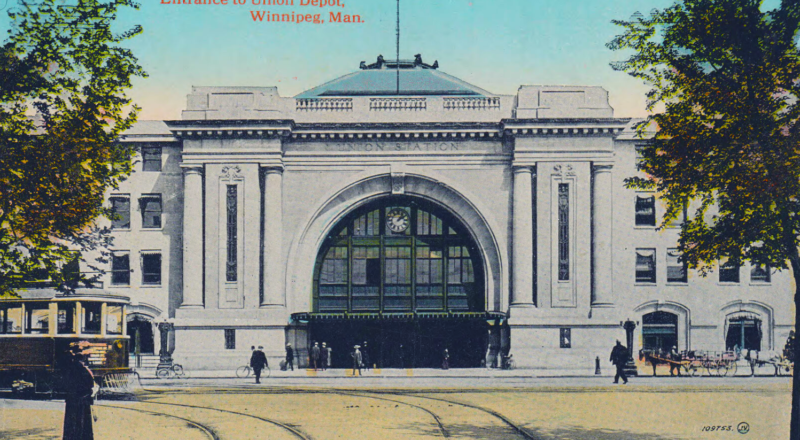

The Main Street entrance of Union Station, circa 1911-1913.

Source: PastForward

In the early 1900s, traveling by train was the norm and was the main form of inter-country transportation. Canadian Northern Railway (CNR), the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR), and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTPR) were the major lines connecting cities around the country and to the United States. Winnipeg at the turn of the century was an up-and-coming city, still quite young and undeveloped, however, it had begun to grow exponentially faster than any other major city in the country at the time. The choice to build a grand train station in Winnipeg came after a hard-fought effort to move the proposed route of the transcontinental railway from passing through Selkirk, Manitoba, to passing through Winnipeg. Selkirk was initially chosen due to its stable banks and lesser tendency to flood, but after years of diplomacy, confusion, changing governments, and false starts, the line ran through Winnipeg. The railway was expected to attract wholesale trading and bring in a rush of immigration from other countries to aid in the growth of Winnipeg’s economy. At one point there were several trans-border rail lines connecting Winnipeg to American cities such as St. Paul, Minnesota. Winnipeg was on track to become one of the most influential and affluent cities in Canada due to the railway and many traveled to the city in search of a new life, with business plans in hand and high hopes for economic growth.

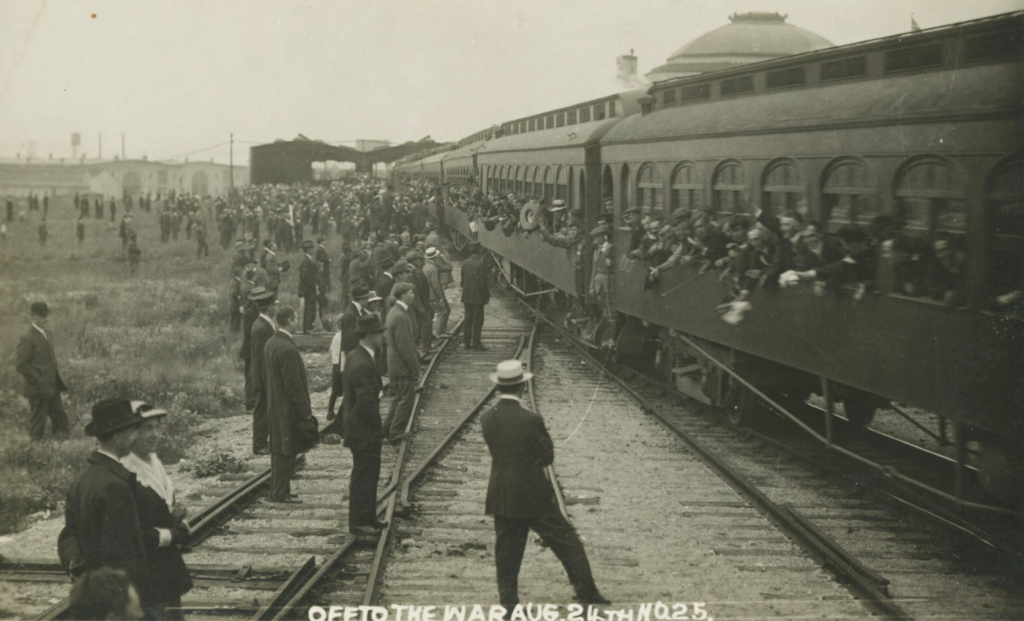

Military personnel depart Union Station (dome visible in upper right corner) during the First World War.

Source: PastForward

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Canadians between the ages of 18-45 began enlisting as soldiers. As a result, train transportation became a necessity for the country. Not only were trains used to mobilize troops, transporting them to training camps, but they were also used to transport ships. Additionally, train transportation significantly contributed to the economy to carry both products and workers needed for the war effort. For soldiers in Winnipeg, Union Station was the beginning of their journey. After leaving Union Station, soldiers would travel east where they would ultimately leave for Europe to fight on the frontlines. Union Station would sadly be for many soldiers the last look at Winnipeg, as over 1000 Winnipeggers would not come back home from war. For those who did survive, Union Station was the site of many happy returns of soldiers reuniting with their families and loved ones after the war ended in 1918.

Unfortunately, as fast as Winnipeg grew, it also saw a quick decline, with a recession taking hold, and labour and wage disputes brewing. There was a large division in class and monetary wealth in the city after the First World War, this evidently divided its citizens. People were not happy with the decisions wealthy businessmen were making and the stance of local government. These issues eventually came to a head in the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike which ultimately created the standard for labour reforms in Canada, however, Winnipeg would never be the same as it was prior to the war. The city, along with the rest of the world, had changed vastly over a ten-year span. There was a lack of money, as the war had grossly affected the incoming trade and the city had been damaged by the economic effects brought by the creation of the Panama Canal which had reduced reliance on Canada’s rail system for international trade. With this time, a new era had come again, after the bright future prophesied at the beginning of the century, the journey in the 1920s was a steep slope that Winnipeg was no longer charging its way up. With the slow decline of passenger train travel around World War II, traffic through Union Station diminished and the future did not look promising. In the 1950s, motorized vehicles began to ingrain their way into people’s everyday lives, and in 1955 bringing with it the end of the streetcar which until then, had been Winnipeg’s only form of public transportation connecting the residential areas to the downtown core.

The downtown atmosphere of Winnipeg has seen a large change since the construction of Union Station; in the early 1900s it was alive with new businesses, events, and people filling the streets on a daily basis. The surrounding municipalities were not yet incorporated into today’s residential suburbs and the majority of Winnipeggers lived close to the downtown core, thus aiding in the population of people interacting in and around places in the heart of the city. This fact changed with the urban sprawl of the post-war era and an influx of blue-collar workers commuting to the city during the day while then retreating to their suburban homes in the evening, leaving downtown emptier and less populated than ever before. The age of rail travel in Canada had seemingly passed as vehicular travel became more mainstream after the second World War.

A postcard featuring Union Station, circa 1911-1916.

Source: PastForward

Union Station once was at the heart of a bustling city, fresh with potential and full of ideas for the future. As the city grew and was constantly changing, the station remained virtually the same besides a few renovations completed over the years, including the recent restoration to the main rotunda ceiling in 2014. Heritage Winnipeg presented Via Rail Canada and Bridgman Collaborative Architecture with an Annual Preservation Award for this work in 2015, recognizing excellence in commercial conservation. The station has always been a strong part of Winnipeg’s diverse architectural history, and it was formally recognized as a historical monument on June 15th, 1976, by the Historic Sights and Monuments Board of Canada. CNR handed over the passenger rail service in Union Station to Via Rail in 1976 and currently hosts two trains, the Canadian and the train to Churchill, the rest of the building however contains offices and other spaces for non-railway tenants. Tracks 1 and 2 are now the location of the Winnipeg Railway Museum, home to Heritage Winnipeg’s own Streetcar 356, the last remaining original wooden streetcar in Winnipeg.

From February 15, 2015, to the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day on November 11th, 2018, Union Station was home to an interactive digital First World War Memorial. In the newly-restored atrium of the station, visitors were invited to reflect on Canada’s involvement in the First World War. The memorial included a display of the 62,000+ Canadians who lost their lives during the war. Their names, rank, and ages are animated on-screen along with pictures of the war, giving visitors a glimpse into the experience of the soldiers. Moreover, all 62,000+ names were displayed together as an attempt to share the scope of the war’s impact on Canadians today. The project was designed with the Union Station’s original architecture and aesthetic in mind. The memorial’s projection panels were made to seamlessly fit into the station’s existing windows as well as the custom projectors which accommodated their structural surroundings. All of the content from the project is available on the First World War Memorial Installation website.

Plans for the future of Winnipeg’s downtown life are ever-changing, there is a strong affection for the city, and its citizens wish to see downtown thriving and flourishing once more. But the question remains now of, where do we go from here? Currently, downtown Winnipeg is undergoing a slight facelift, especially after the event of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a push to bring the citizens of Winnipeg back downtown, even if they are no longer commuting there for work. Places such as the Exchange District and The Forks have maintained their hold on the arts and culture scene and continually act as the source for many events and activities that bring people out of the suburban depths, even if for temporary purposes. However, with the addition to places around downtown such as True North Square and the restoration of many historical buildings down Main Street, we now have begun to bridge a connection between these cultural hubs and attract a new generation of Winnipeggers that seek to breathe life back into the city through a modern lens.

Winnipeg has ushered in a new era and embraced, engaged with, and renewed the architecture and historical sites that make up the downtown core, instead of forgetting that they exist but to include them in the future of a better Winnipeg. Plans for the future of Union Station however are as of yet, undetermined, the city has proposed that the tracks currently housing the Railway Museum be reclaimed for the creation of a rapid transit hub, hoping to connect downtown to the surrounding neighbourhoods. To act as a literal gateway into the Forks site, to invite foot traffic as opposed to vehicular travel, and to bridge a connection to the surrounding areas. To many, heritage buildings may appear as simply grey or brown structures that someone built a long time ago. However, the buildings stand for more than just their facades or streetscape appearances, they stand as historical landmarks, physical markers of the hopes, dreams, and memories of the shopkeepers, business owners, families, and train travelers that occupied them in the past. They should be a large part of those future memories with many more stories to tell! Heritage buildings are deeply important to the cultural significance of cities, though they also enrich education, enhance the quality of life, promote sustainable development, and engage their communities. Conserving heritage buildings can bring strong economic benefits as well, they can create local jobs and help create a city identity, thus aiding tourism and immigration efforts. Everyone at Heritage Winnipeg has high hopes for the future of the downtown and with it, Union Station. We will continue to advocate for and appreciate the works of heritage structures that populate the city we love!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Jackie Craven, “What is Beaux Arts Architecture?” thoughtco.com,

Via Rail “Centennial of Winnipeg’s Union Station” viarail.com,

Barbara Maranzani. “Grand Central Terminal: An American Icon” history.com. February 1, 2013.

Randy Turner “City Beautiful, How Architecture Shaped Winnipeg’s DNA” Winnipeg Free Press.

Ruben C. Bellan, "Rails Across the Red - Selkirk or Winnipeg"

“Union Station/ Winnipeg Railway Station, National Historic Site of Canada” Historic places.

"First World War One Memorial", Pattern Interactive Blog

"Off to War, Aug 24th." Collected by Martin Berman. Winnipeg Public Library Collections

Heritage Winnipeg, "First World War Memorial Installation."