/ Blog

March 16, 2022

Renovated & Restored History: The Ukrainian Labour Temple

It is now March and our 36th Annual Preservation Awards are fast approaching! We are proud to announce that this year’s awards will be hosted at the Ukrainian Labour Temple, therefore, Heritage Winnipeg thought it would be a great idea to showcase and applaud them for the extensive conservation work undertaken.

Over the years, Heritage Winnipeg has written a few blogs on the Ukrainian Labour Temple, however, the building recently underwent major preservation/restoration including universal accessibility. As a result, the Labour Temple has become an excellent example of how a heritage building can be updated to accommodate current building codes while maintaining its historic integrity and character-defining elements. Moreover, the Labour Temple’s history is deeply ingrained in our city’s past, and it is recognized as a heritage building by all three levels of government, making it worthwhile to step back in time and rediscover this North End gem.

The Ukrainian Labour Temple’s history begins years before the building’s actual construction. Beginning in the late 19th Century, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier‘s government introduced a series of policies to populate the prairies while growing the country’s agricultural sector. These programs supported the construction of regional and transcontinental railway lines while attracting European immigrants with the promise of cheap or even free farmland. Therefore, Wilfrid’s policies were very influential in bringing a large population of Ukrainians into the prairies, particularly Winnipeg.

While most Ukrainian immigrants moved onto homesteads in rural areas, some decided to stay in Winnipeg, taking up industrial factory jobs. Most of these jobs were located in the neighbourhoods of the North End and Point Douglas. As a result, urban-dwelling Ukrainians moved into these neighbourhoods, creating rather large Ukrainian communities within the city. As the Ukrainian population in Winnipeg grew, so too did the need for their own community space. In 1906, the first Ukrainian community centre, called the Winnipeg Labor Temple, was built on James Avenue.

The Winnipeg Labor Temple was a four-storey brick building, containing 17 meeting halls and committee rooms. The James Avenue Temple was used by nearly 80 unions for social activities, political campaigns and organization of workers. It was integral to the Ukrainian community, which continued to grow in Winnipeg. In March of 1918, representatives of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, the Volodymyr Vynnychenko Drama Circle and the weekly newspaper Robochyi narod agreed that a more modern and larger meeting hall was needed for the growing Ukrainian community. From that meeting, the Ukrainian Labour Temple Association (ULTA) was formed to coordinate the construction of the hall we know today.

At 591 Pritchard Avenue stands the Ukrainian Labour Temple. It is the first and largest Ukrainian Labour Temple to be built in Canada. Constructed from 1918 to 1919, the Labour Temple was built entirely by volunteers. During the time of the construction, the Free Press reported that the building cost roughly $50,000 with all the funds coming from donations by the community’s 1500 members. The building is one storey high with a basement. It contains a large hall and theatre space that could hold 650 people with an additional 200 on the balcony. The Temple also contains two libraries, a printing plant and classrooms.

The building’s architecture is an excellent example of neoclassical design. This style draws inspiration from classical architecture styles as a revival of certain design elements popular during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Neoclassical architecture is usually characterized by grandeur scale, geometric designs and elaborate ornamental detail on both the exterior and interior. The overall scale of the Labour Temple is grand with the main meeting hall immediately impressing visitors the moment they step inside. From the design and construction of the Labour Temple, it is clear that this building was made with the sole intention of creating a welcoming space that could accommodate a variety of community services and events.

The Labour Temple’s initial design was met with some contention. This was not because of the size of the building, nor was it about the appearance – it was about who had designed it. The Ukrainian Labour Temple was designed by Robert Edgar Davies. During the time of construction, Davies was in hot water with the Manitoba Association of Architects (MAA). Starting in 1914, the MAA had made a requirement that all practising architects had to meet certain standards set by them. These standards would be tested through a series of examinations. Davies did not pass the MAA’s tests, therefore could not become a member of the MAA nor practice as an architect. With that said, Davies disregarded the MAA’s rules and called himself the architect of the Labour Temple. This caused the MAA to pursue legal action against him. Davies never became a member of the MAA nor a certified architect, but he is listed as the architect of the Labour Temple by the City of Winnipeg Building Permit Records.

From its construction in 1919, the Labour Temple has been a major centre for trade unionists and socialist politics. It continues to host activists, politicians and educators of left politics to this day. The founders of the Labour Temple all upheld socialist political views. As a result, the print shop found within the Labour Temple was used to print and distribute Working People, a Ukrainian newspaper that shared socialist messages and views. The Labour Temple was also used as the meeting place for the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party.

The Ukrainian Labour Temple opened in February of 1919, just months before the Winnipeg General Strike. During the six weeks of the General Strike, the Labour Temple played an important role. The Temple was used for hosting meetings and utilized for its print shop to produce pro-strike publications and information. During this time, the Ukrainian Labour Temple was raided by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, seizing all correspondence and other pro-strike and socialist material. However, by the end of the General Strike, the Labour Temple remained an institution for Ukrainian political and cultural life within Winnipeg.

After the Strike, the Labour Temple began expanding its activities and involvements within the community. For example, in 1921 the leaders of the ULTA were involved in the establishment of the Workers Party of Canada (a communist party). Later in 1922, the Women’s Section was created, offering women of the ULTA services and activities. These women’s groups mainly focused on fundraising efforts to sustain their Labour Temple but also offered classes such as reading and writing.

The ULTA continued to expand its services, introducing children’s groups and activities. By 1922, schools were established in Labour Temples all across Canada, and Winnipeg’s Ukrainian Labour Temple was no exception. The ULTA also founded the Worker’s Benevolent Association in 1922. The Worker’s Benevolent Association was created to provide injury, sickness and life insurance for workers who did not have access to such benefits.

In 1924, the ULTA became a national organization, changing its name to the United Labour-Farmer Temple Association (ULFTA) to accommodate its growing rural membership. Moving forward, the ULFTA would change its name for the last time in 1943 to the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians (AUUC) which is what it is known by today. The Ukrainian Labour Temple on Pritchard has remained a gathering place for progressive politics and activism, as well as a place that celebrates and preserves Ukrainian culture within the city.

Recently, the Ukrainian Labour Temple set out to tackle the complicated task of modernizing its historic building. The Ukrainian Labour Temple is recognized as a heritage building by all three levels of government. Both federal and provincial designation gives the building heritage recognition, however, municipal destination requires a heritage permit so the Ukrainian Labour Temples’ restoration project followed specific rules and regulations. As a result, the Labour Temple was restricted in what and how they could change certain elements of the building. With that said, the Labour Temple’s renovations did not only include new modern upgrades, but also restorative work that has brought back a few historic details and character-defining elements to the building.

The first and arguably most important priority of the Labour Temple’s renovation was to make the building accessible for all. This meant installing an interior lift that would provide visitors access to both the main floor and the basement. The Labour Temple also upgraded all of the washrooms and put universally accessible washrooms on each floor. These renovations may have been strictly modern additions, however, they are necessary for the continued use of the Labour Temple in the future, as they allow more visitors to use and enjoy the space. Moreover, these renovations preserve the future of the building by showing how modernizing projects can be done in a manner that still respects the historic character of the building.

While the modern upgrades to the Labour Temple were being made, restoration work on the building was simultaneously completed. First, the glass blocks on the windows that were installed sometime in the 1960s were replaced with new windows, restoring the building’s exterior facade to its original 1919 appearance. The foyer was restored to reflect the original grandeur of the soaring high ceiling and the original exterior doors were also restored. These large changes are striking and bring the building back to its former glory, however, smaller changes have not gone unnoticed. For example, the Labour Temple has added much-needed storage in the building without changing the original appearance and finishes of the hall. Electrical and mechanical upgrades have also been made to meet modern building codes, all without taking away from the building’s historic integrity.

Over its 103 years, the Ukrainian Labour Temple continues to remain a historic staple in the North End. The recent renovations of the building prove that the modernization of a heritage building does not need to come at the cost of losing its historical integrity. Instead, it celebrates the adaptability of restoration projects and how heritage can be upheld for years to come. That is why the Ukrainian Labour Temple is the perfect setting for the 36th Annual Preservation Awards! As a nominee, it shows Winnipeggers the beauty and history behind maintaining and updating this heritage building.

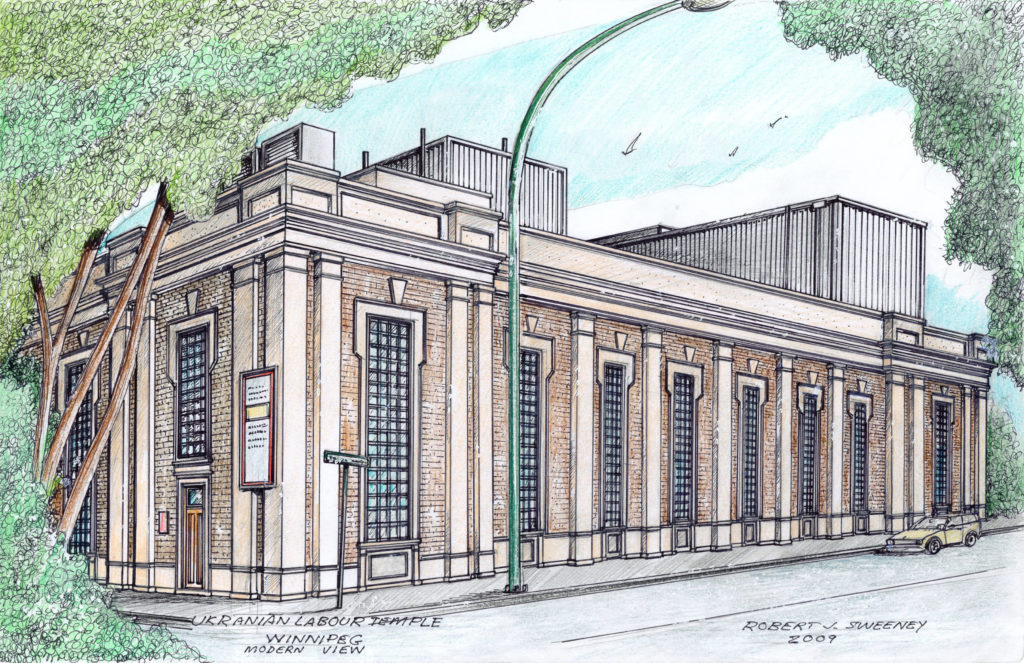

Ukrainian Labour Temple, Winnipeg, Modern View, 2009. Print by Robert Sweeney available at the Heritage Winnipeg store

“We look forward to hosting the 36th Annual Preservation Awards. Our members feel honoured to be recognized for the hard work and effort that was put in by everyone involved. Not only our volunteer members, but the architects, contractors, and sub-contractors who went above and beyond to create a place we can be proud of for many years to come.” – Tim Gordienko from the Ukrainian Labour Temple

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

591 Pritchard Avenue, City of Winnipeg Long Report

Heritage Winnipeg, "The Ukrainian Labour Temple," November 3, 2016.

Heritage Winnipeg, "The Last One Standing: The Ukrainian Labour Temple," May 22, 2019.

National Union, Ukrainian Labour Temple

University of Manitoba, The Ukrainian Labour Temple Association PDF

Culture Days, Tours of the Historic Ukrainian Labour Temple

Association of United Ukrainian Canadians, "100 years of our contribution to Canada."

Public Board, "Spreading The Word About Canada."

Heritage Winnipeg, Annual Preservation Awards Nomination Form.

Manitoba Historical Society, "The Ukrainian Labour Temple"

Historical Information on the Ukrainian Labour Temple provided by Tim Gordienko