/ Blog

March 6, 2019

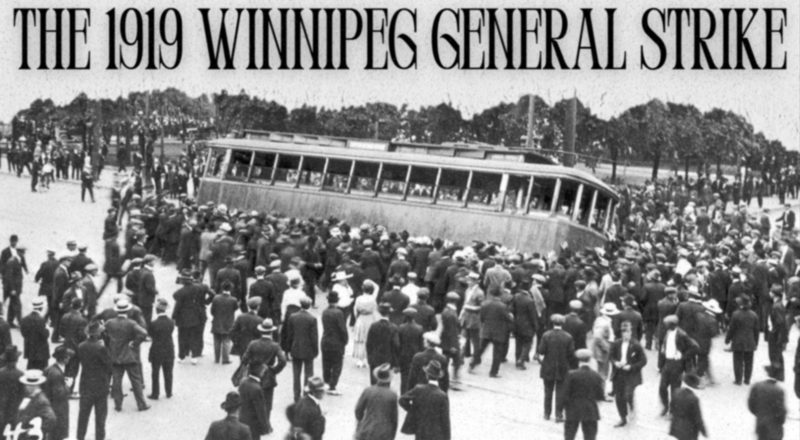

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike: Population Growth and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station

As 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, Heritage Winnipeg is commemorating the year by looking back at the events during this tumultuous period of history that helped shape our city. This article is part of a series of guest posts reflecting on the some of the places that bore witness to the Strike and the events leading up to it. Read all the blogs in this series from the beginning:

Walker Theatre Meeting Sets the Stage

Population Growth and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station

The Western Labour Conference in Calgary

Breaking Point – Contract Negotiations Stall

The Strike Shuts Down Winnipeg

Veterans Protest With and Against the Strike

Specials and Strikers Riot

Raids and Arrests

Bloody Saturday

Russell Sedition Trial

Economic and social conditions in Manitoba were dramatically changing at the turn of the 20th century, and laid the foundation for the Winnipeg 1919 General Strike. In particular, immigration from Europe increased dramatically, bringing a stream of workers and their expectations for a new life. Families from Britain, Poland, Germany, Hungary, Russia, Iceland and Ukraine moved to Canada to take up farming and then work in the industries of an expanding economy. With this migration came a strong sense of ethnic group affinity, a deep understanding of class differences, and a capacity for facing difficult conditions. While this migration was designed by government policy to develop the economy, it also created new challenges for social relations, urban planning and political systems that were unpredictable.

A massive new wave of immigration started around 1896. The Canadian Pacific Railway Station on Higgins Avenue (now the Neeginan Centre) was the last stop for thousands of new Canadians as they started new lives. While all of Canada was growing because of immigration, Winnipeg received a disproportionate number of people: Canada’s population grew by 20% and Manitoba’s by 81%. Winnipeg grew by 320% between 1900 and 1921, from 42,450 to 179,080 residents. By 1911 the population of Canada was 7,206,643, 22% of which were born outside Canada. 49% of the immigrants were born in the British Isles, 19% in the U.S., and 47% were naturalized citizens. While some immigrated from Asia and Africa, 97% of the population was of European origin.

For many immigrants, their first years in Canada were physically difficult and emotionally disappointing. They came to Canada with very little, there were harsh conditions to deal with immediately, and there was limited work and government support. Many spent long periods in ‘settlement camps’. In 1899 for example, there were so many immigrants without land allocated that the government hastily moved 80 Ukrainian families to an abandoned logging camp south of Riding Mountain. In a two-week period nearly 50 people, most of them children, died of scarlet fever. There was virtually no government support, no social safety net, no public health. There was very limited public security, transportation and information.

To sustain themselves and their families, many men left the farms to work on the railway or in the lumber industry for part of each year. They persevered and organized in different ways to improve their living conditions, establish their churches and synagogues, schools, community centres, and cultural organizations. By developing and strengthening their cultural institutions, thousands of immigrants created new homes and a sense of place in the Canadian landscape. As Adele Perry wrote, “Turn of the century Winnipeg was a place of both immigrant possibility and immigrant strife. For much of the left, the poverty and social dislocation of new immigrants and their vulnerability to insufficient infrastructure came to stand as a powerful symbol of the inability of capitalism to meet basic human needs.”

In the north end, families were often crowded into cheap housing, single men were often homeless, children were working, and sanitation was limited. Housing was quickly and poorly constructed on narrow 25 or 32 foot lots by developers who squeezed as much construction as possible into their allocations. In 1913 only about half of the houses were connected to the city water and sewer system and therefore many had an outdoor toilet, the infamous ‘box closet’. Garbage was collected by private ‘scavengers’ for a fee. Crowded and unsanitary conditions led to frequent outbreaks of typhoid fever, smallpox, and other communicable diseases. According to a City Medical Report in 1905, “… the filth, squalor and overcrowding among the foreign elements is beyond our power of description.” In winter there was a constant smoke haze from bituminous coal and wood fires from the homes or belching from the industries on Sutherland Avenue.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Guest post written by Dennis Lewycky.

Edited by Heritage Winnipeg.