/ Blog

April 3, 2019

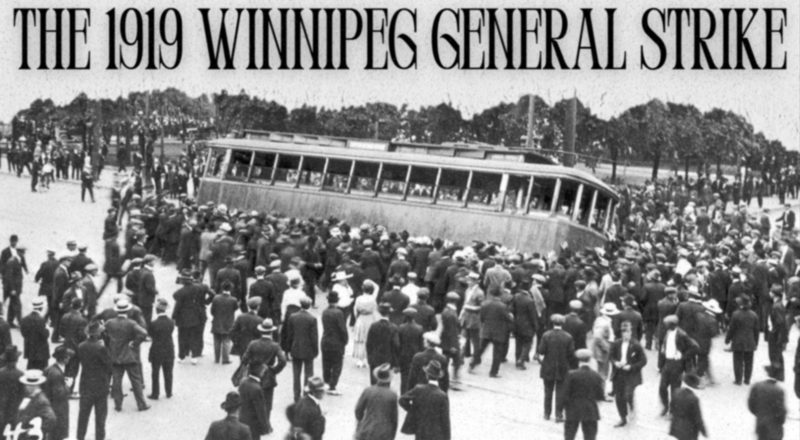

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike: The Western Labour Conference in Calgary

As 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, Heritage Winnipeg is commemorating the year by looking back at the events during this tumultuous period of history that helped shape our city. This article is part of a series of guest posts reflecting on the some of the places that bore witness to the Strike and the events leading up to it. Read all the blogs in this series from the beginning:

Walker Theatre Meeting Sets the Stage

Population Growth and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station

The Western Labour Conference in Calgary

Breaking Point – Contract Negotiations Stall

The Strike Shuts Down Winnipeg

Veterans Protest With and Against the Strike

Specials and Strikers Riot

Raids and Arrests

Bloody Saturday

Russell Sedition Trial

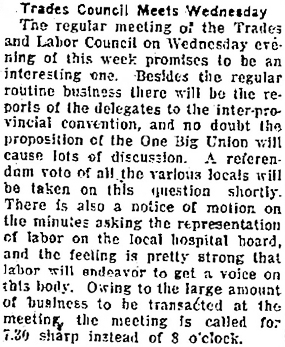

In March 1919, about 240 union delegates attended the Western Inter-Provincial Convention in Calgary to discuss a number of common issues. The conference followed the Quebec City TLC convention the previous September, and the purpose was to assure “the voice of protest should be heard”. Delegates from Winnipeg put forward one resolution on a six-hour work day and a five day week for all labour. Union representatives discussed strengthening their bargaining power and endorsed the concept of industrial unionism. The model proposed was to create One Big Union (OBU) to bring together all the unions in Canada, to collaborate and provide both bargaining and political support. While the idea of unifying unions across Canada was not novel, the industry base versus the craft base to unionization was reflecting significant change to come. The unions were seeing proof they could exert more power when workers collaborated with other trades or within industrial sectors.

Source: Lethbridge Herald March 25, 1919, page 12 (public domain)

The impetus for this collaboration was the need for greater practical and political ability when bargaining with employers. Expanding the number of union members who could strike would create a more formidable incentive for employers to bargain. Politically, the OBU concept represented how unions were seeking authority to address industrial relations beyond specific workplaces. To industry and government representatives, if the OBU existed, there would be a weakening of their authority over labour. Workers could then have some influence on workplace issues, industry and government policy and the economy.

The Calgary Convention placed the western unions onto a distinct political path. One of the resolutions passed at the conference referred to, “The Orders in Council is a negation of all that we have fought for and obtained for centuries. We do not propose for a moment to sacrifice those liberties.” Another resolution, “Be it resolved, that this Conference places itself on record as being in full accord and sympathy with the aims and purposes of the Russian Bolshevik and German Spartacan Revolutions and be it resolved, that we demand immediate withdrawal of all Allied troops from Russia.”

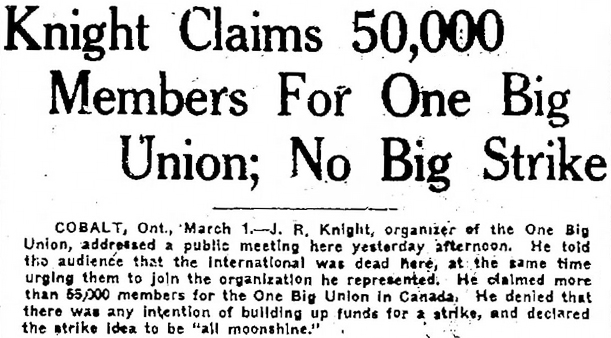

The OBU energized some of the unions in the United States, particularly as it was promoted by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). It acquired the profile of a more militant and aggressive style of union organizing with a commitment to industrial unionism and working class political engagement. In Canada the OBU founding congress was on June 4, 1919. A poll conducted by the Winnipeg Trades Labour Council found 8,841 to 705 of the members responding supported the OBU (July 12, 1919). But in the next couple of years, it had more of an influence on government as a threat, rather than as an actual organizational or political force. In the 1920s it only mustered together a few thousand members in a loose group of unions. The OBU was weakened by resistance from employers, from within the established unions and by government. However, the OBU maintained a presence among unions, representing a more intense posture on principles and issues to support the working class.

Reflecting on the impact of the OBU, political analyst Ian McKay notes that, “It may have had as many as 50,000 members at its peak in 1920, which made it by far the largest home grown left-wing organization found in Canada in the entire period 1890-1920.” Importantly, the OBU was more than unions merely trying to establish collective bargaining. For McKay, the OBU was the means by which workers could take “ever-increasing amounts of economic and cultural power from their rulers; a working class revolution taking place through the logic of social evolution.”

Source: Lethbridge Herald March 1, 1920, page 1 (public domain)

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Guest post written by Dennis Lewycky.

Edited by Heritage Winnipeg.