/ Blog

June 21, 2019

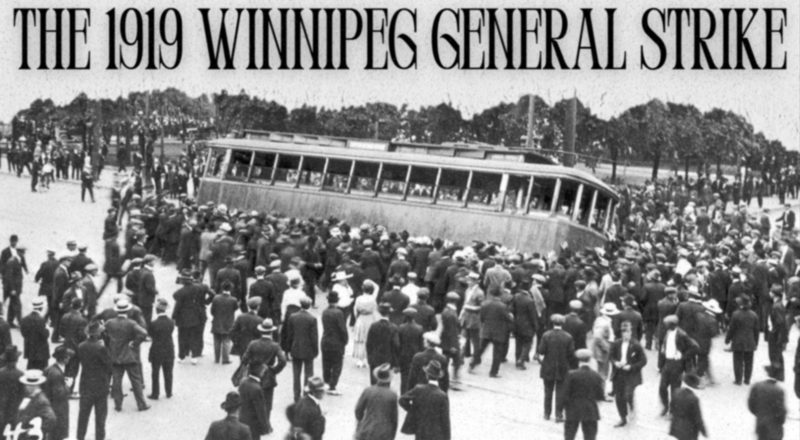

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike: Bloody Saturday

As 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, Heritage Winnipeg is commemorating the year by looking back at the events during this tumultuous period of history that helped shape our city. This article is part of a series of guest posts reflecting on the some of the places that bore witness to the Strike and the events leading up to it. Read all the blogs in this series from the beginning:

Walker Theatre Meeting Sets the Stage

Population Growth and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station

The Western Labour Conference in Calgary

Breaking Point – Contract Negotiations Stall

The Strike Shuts Down Winnipeg

Veterans Protest With and Against the Strike

Specials and Strikers Riot

Raids and Arrests

Bloody Saturday

Russell Sedition Trial

The June 17th raids and arrests provoked criticism across Canada. Protest marches against the government and police action were organized in the major cities of the west. The Strike had become a national protest as it dovetailed with labour unrest in the rest of Canada. On Saturday, June 21st, a peaceful protest organized by the veterans led to a violent confrontation known as Bloody Saturday at the corner of Main Street and Market Avenue. Estimates of 5,000 to 8,000 veterans, striking workers and curious citizens stood along Main Street near City Hall and Market Avenue. Mayor Gray requested emergency assistance from the Royal North West Mounted Police (RNWMP) and the military to control the crowd. They arrived at the corner of Portage Avenue and Main Street, armed, on horseback or in military vehicles, ready for confrontation.

A streetcar traveling along Main Street was stopped, knocked off the tracks and damaged by the protestors. Soon after and without warning, the RNWMP rode into the crowd on Main Street, swinging bats and then using their revolvers. Two civilians died, a couple were seriously wounded, and almost 100 people were treated in hospital. Ninety-one people were arrested – eleven were women.

Leslie Paulley, a 17 year old office boy working for the Canadian Pacific Railway, was at the protest:

Now I don’t mind frankly confessing to you, I’ve always felt an inner sense of gratification in the memory that amongst others I too threw a stone at the charging Mounties. My only regret was that my aim was so dam poor – I missed.

Arthur Thompson worked near City Hall and watched the demonstration disintegrate:

Our office then was on the corner of Main and McDermot and we were looking out the window. … Next to our office there was a building in a state of disrepair. Some of the strikers were up on the roof of this building breaking loose bricks which they were pelting at the soldiers, at the mounted men. … And then somebody threw a bottle that caught one of the mounted men on the back of the head and knocked him unconscious.

The next day a meeting held at Victoria Park was filled with mourning for what happened and for the dead. The Strike was now elevated to a higher political level than intended, and many workers felt they lost their voice in the dispute. Everyone seemed to know the Strike was over. A day later, the Central Strike Committee called for the Strike to end on June 25th.

The strikers did not get a ‘living wage’ and ‘collective bargaining’ was not established across the board in labour-employer relations. The third demand of the strikers, to reinstate workers who struck was only partially met. The building trades unions that went on strike first were able to negotiate a 15% an hour increase in wages but the employers did not give up their control of setting wages. The metal workers were able to reduce work hours from 55 to 50 a week. Neither of the Trades Councils gained recognition.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Guest post written by Dennis Lewycky.

Edited by Heritage Winnipeg.