/ Blog

November 6, 2019

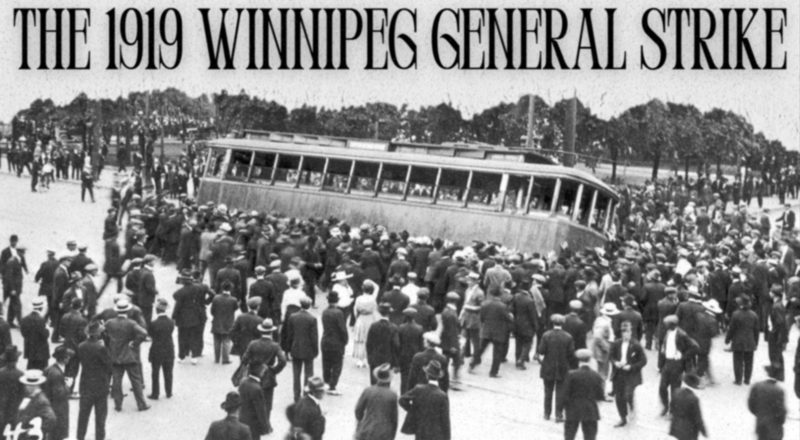

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike: Russell Sedition Trial

As 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, Heritage Winnipeg is commemorating the year by looking back at the events during this tumultuous period of history that helped shape our city. This article is part of a series of guest posts reflecting on the some of the places that bore witness to the Strike and the events leading up to it. Read all the blogs in this series from the beginning:

Walker Theatre Meeting Sets the Stage

Population Growth and the Canadian Pacific Railway Station

The Western Labour Conference in Calgary

Breaking Point – Contract Negotiations Stall

The Strike Shuts Down Winnipeg

Veterans Protest With and Against the Strike

Specials and Strikers Riot

Raids and Arrests

Bloody Saturday

Russell Sedition Trial

November 1919, Court House:

When the Strike ended, the police and legal officials had eight men out on bail (Armstrong, Bray, Heaps, Ivens, Johns, Queen, Pritchard, Russell) and four men in jail (Charitonoff, Schoppelrie, Alamazoff, Verenchuk) but were not sure what to do with them.

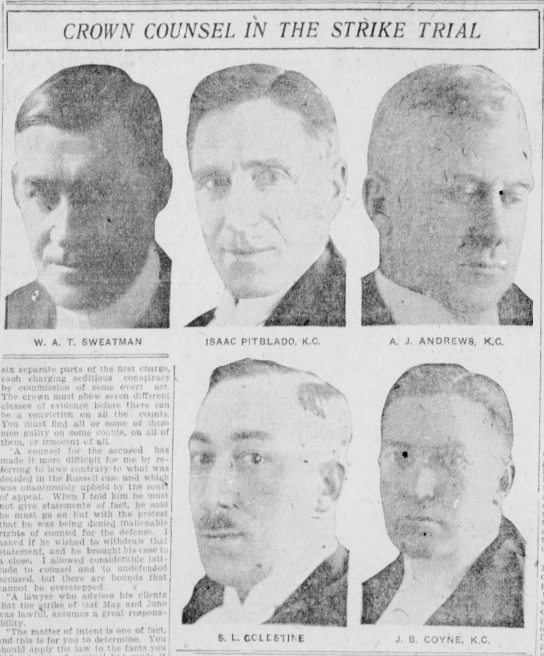

The crown council for the trials against the strike leaders. A.J. Andrews is the man on the top right.

Source: Winnipeg Tribune, 1920-03-27, page 12 (public domain)

The men had been arrested under provisions of the Canadian Criminal Code, though the Attorney General, Charles Doherty, had not given approval to make the arrests. After the arrests, the police did get the authority from the Minister of Immigration to apprehend the men, so the police could claim the men were suspected of Immigration Act violations. The situation was generating public concern, and even the British Labour Party protested the arrests and said the men should not be deported. Dropping charges and letting them go would imply the government made a mistake in the arrests. Naturally, then, letting them go was not an option.

The best legal option available was to put the men on trial as ‘leaders of The Strike’, and accuse them of sedition, or, essentially, of advocating the over-throw of the Canadian government. The problem with this option was that the provincial government was responsible for sedition related prosecutions, and the Attorney General did not believe there were grounds for prosecution. He said he would not take the men to court. The only option left to A.J. Andrews and the Citizen’s Committee of 1,000 was a ‘private prosecution’, which was allowed under the criminal code and would not require the Attorney General’s sign-off. If the justice system could not or would not prosecute, a citizen or group of individuals could allege a violation of the law and take an accused to a court for judgment.

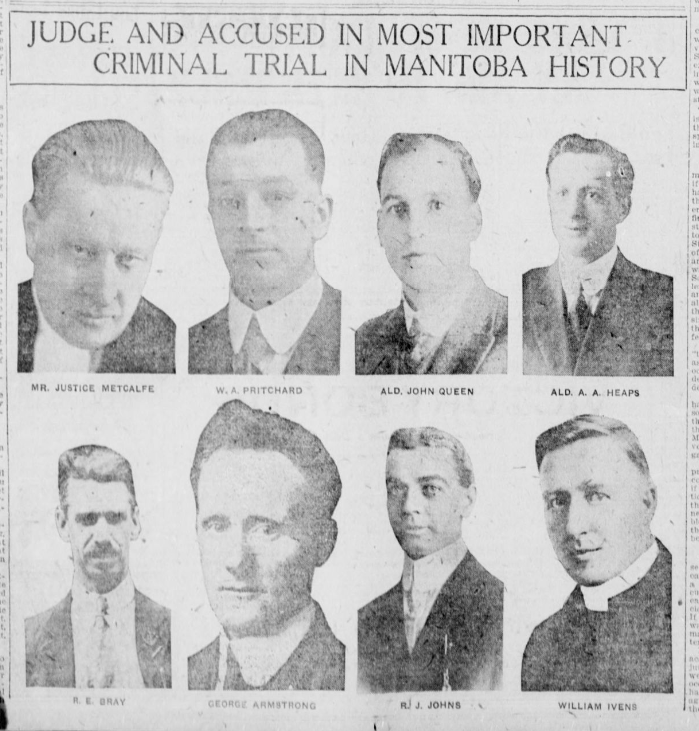

Portraits of the arrested strike leaders.

Source: Winnipeg Tribune, 1920-03-27, page 12 (public domain)

Bob Russell was put on trial first in November 1919, at the Courts on Broadway. He was considered a central figure in The Strike. He was a member of the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council, the Central Strike Committee, and the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC). He was the secretary of the Metal Trades Council and a promoter of the One Big Union.

While 10 men were labelled ‘strike leaders’, probably only Russell fit that title. He was an ardent union leader and open socialist, both of which were completely legal activities in Canada. But the prosecution set out to prove Russell had conspired to agitate dissent, to encourage others to destroy the legitimate government of the country, and to install a soviet style government. There were seven points to the indictment that claimed Russell and the others (the seven to be tried later); conspired to foster disaffection against the government, aided and abetted the publication of seditious literature, conspired to effect a seditious intention (an unlawful strike), ultimately these were steps in a revolution, which would obtain control of industry and property, introduce a soviet form of government and this was done by being a ‘common nuisance’ for the general public through The Strike.

Andrews was the lead prosecutor in the Russell trial. He focused attention on what he claimed was a key issue in the charges against Russell and the others, “ that their intention was to bring about discontent and dissatisfaction and what would be the logical result someday – revolution – someday attempted revolution – someday overturning the government”.

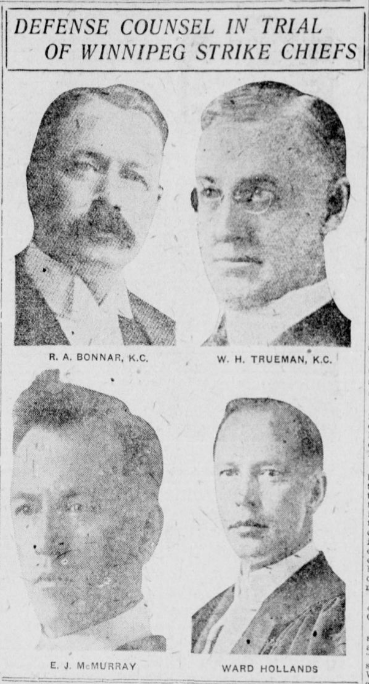

The Russell defense team started by unequivocally stating there was no conspiracy among the men accused. Edward McMurray, defense council argued there was no collusion among the men who had very different ideals, social backgrounds and political affiliations (Dixon ran against Armstrong in the 1915 provincial election for different political parties). They put forward that Russell acted within his legal rights as a labour leader and a member of the SPC. They demonstrated how Russell made efforts to find a settlement to The Strike and therefore was not seditious in his actions.

The defense lawyers involved for the strike leaders trials.

Source: Winnipeg Tribune, 1920-03-27, page 12 (public domain)

The defense pointed out there was no evidence to single out Russell as a ‘strike leader’. In fact, James Winning, President of the WTLC acknowledged at trial and under oath that he was responsible for ‘leading the strike’ through the CSC. Russell, Armstrong and Ivens were CSC members and were labeled ‘strike leaders’. None of the 12 other CSC members were labeled strike leaders and had criminal charges brought against them. Instead, the prosecution selected men for trial who had a public profile, men who were articulate speakers and advocates, who held strong pro-labour views or were active socialists.

After the prosecution presented 703 pieces of evidence (largely publicly available books, magazines and documents) and a dozen witnesses over seven weeks of trial, Russell was found guilty on December 24 (the judge allowed Russell to go home unescorted for Christmas Day). He was sentenced to two years in prison (though we would only served 11 months). Bill Ivens summarized public opinion, “The vitriolic attack of the daily press had deliberately poisoned the mind of the public. Bob Russell was tried by a poisoned jury, by a poisoned judge, and he is in jail tonight because of a poisoned sentence”.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Guest post written by Dennis Lewycky.

Edited by Heritage Winnipeg.