/ Blog

April 8, 2021

All Aboard! Tourism on the Rivers

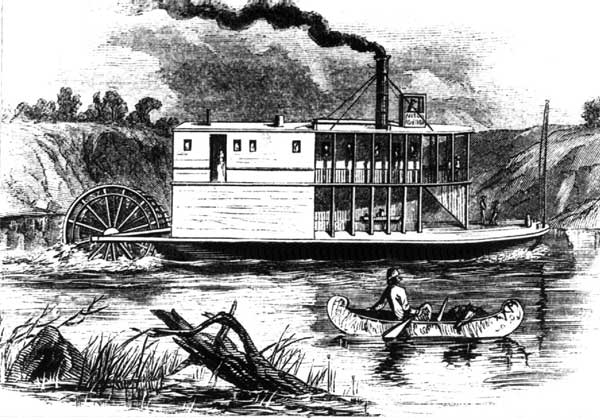

As the weather begins to warm, and the ice on the Red and Assiniboine rivers melt away, a familiar sight will grace our waterways once again. The water taxis will start running, boat tours will begin again, and pleasure crafts will take to the water. All of this excitement pales in comparison to the boats that once traversed Manitoba’s waterways!

For centuries the only boats used on Manitoba rivers were canoes, made of birch bark and used by Indigenous communities for trade and travel. These canoes would eventually be adopted by the fur traders and voyageurs who came through Manitoba on behalf of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and North West Company.

With the voyageurs came settlers, and by the early 1800s a number of trading posts had been established by the HBC with European communities cropping up alongside them. Larger communities necessitated larger boats, to bring people and supplies, and the first riverboat arrived in Winnipeg in 1859.

The Ansom Northup, owned and operated by an American businessman of the same name, sailed in from Minnesota on June 10th, 1859, landing at the site of the present day Kildonan Park. Further boats would follow the same path, bringing with them building materials and workers, and all the many things needed to build a growing settlement. Access to specific types of wood and stone would not have been possible without the use of the steamship and even after the railroad started to reach Winnipeg, many still relied on commercial steamboats to bring in materials. Steamboat service was more reliable than the trains, and often faster, though the freight cost was more expensive. Over the next fifteen years, more and more boats could be spotted travelling up and down the Red River.

Steamships also became an invaluable part of the Manitoba economy. The HBC had added a steamboat warehouse to their building collection in 1872, and in 1876 it was the S.S. Minnesota that hauled away 5,000 bushels of grain near Lombard Avenue, that kicked off the Manitoba grain trade.

Some of these boats, such as the Ripple (whose engines failed twice across less than a decade of service), were built in Winnipeg while others arrived from further shores. Along the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, docks were built to accommodate the river traffic. The Rover Docks opened in 1915, located parallel to Rover Avenue between Annabelle and Syndicate Streets. The docks were jointly managed by the City of Winnipeg and the St. Boniface Harbour Commission, and measured 400 feet in length and 30 feet in width. The total cost of construction was $25,000. For the next several years, the Rover Docks were mostly used to unload cut timber. As private docks opened at industrial sites, they found themselves out of use by 1929.

The city then built the Alexander Docks (70 Alexander Avenue) in 1929 to replace the Rover Docks. Built along Alexander Avenue in the present-day Exchange District, the Alexander Docks were closer to Winnipeg’s industrial hubs – namely, the warehouse district and the nearby CPR Station. As well, the area we know as Waterfront Drive was used to connect the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Canadian National Railway Lines. In other words, it was the ideal place to construct a new dock. The river was dredged 13 feet to accommodate the space needed, and construction was completed in the late spring of 1929. Many different types of vessels stopped here, from government boats, cargo steamers, tug-towed barges, and even passenger ships.

As Winnipeg grew, some captains and company owners steered away from commercial freighting and set their sights on a new business model: recreation and tourism. By the 1900s, there were many picturesque riverside parks and equally as many people looking to pay them a visit. Perhaps this is why there were upwards of 1,000 people in attendance at the christening of the Winnitoba in 1909.

The Winnitoba was launched in the City of St. Boniface, near where the Seine River meets the Red River. Among the considerably-sized crowd was then-premier Rodmond P. Roblin, St. Boniface Mayor Joseph Alfred Fereol Bleau, and City Controller Richard Waugh (on behalf of Winnipeg Mayor William Sanford Evans). There was also a representative from Minnesota and MP Alexander Haggart.

Premier Roblin speaking at the launch of the Winnitoba.

Source: Archives of Manitoba, Transportation – Boat – Winnitoba – #8

The boat’s owner was John Leonard Hyland, who owned Hyland Navigation & Trading Company, a private amusement park (Hyland Park), as well as another ship, named The Bonnitoba. It was Hyland’s three year old daughter Lenore, who christened the boat by pouring a bottle of clear water atop the ships bow. The Winnitoba was one the largest boats yet to sail Winnipeg’s rivers, and featured a number of exciting amenities including modern electrical lighting, sleeping accommodations for 225 passengers, and an on-board kitchen.

The Winnitoba was used primarily to transport people to either Selkirk, or Hyland Park. Largely forgotten now, Hyland Park was an interesting example of early recreation in Winnipeg. Built along the Red River in the RM of East St. Paul, Hyland Park had multiple pavilions, a dance hall, and notably a floating pavilion. John Hyland purchased a barge from the Arctic Ice Company, and renovated this into a floating dance hall – complete with an orchestra. It was moored near Hyland Park’s private dock.

Ill-fortune befell Hyland when both his ships were destroyed, the Bonnitoba by an ice flow in 1913, and the Winnitoba by a fire while at the Hyland Dock in 1912. By 1915, Hyland Park had closed and the Winnitoba was considered lost until remains of the ship were discovered in 1987. Some of the remains have been salvaged and are kept at the Manitoba Maritime Museum. Hyland Park still exists in the RM of East St. Paul, with its public boat launch continuing to invite people to recreate on the Red River over a century later.

Disasters were not uncommon on the Manitoba rivers. Spring ice flows could damage ships, or the boats could simply crash into the shore. Interestingly, one of the biggest stories about a Winnipeg steamship disaster turned out to be untrue. At the turn of the 20th century, there was a thin line separating gossip and news that was made thinner depending on the reporter covering the story. Winnipeg was a strange space, both a rough and tumble frontier town and a growing metropolis, and this made it ripe for strange tales. Journalist Reginald Robinson took advantage of this fact; Robinson worked, at various times for the Winnipeg Tribune, and as a correspondent for American newspapers. He made up tall tales about Winnipeg running rampant with coyotes, or about a prairie homestead so covered in snow that its residents were creating snow tunnels to move around. It’s interesting then, that his most infamous tall tale was the result of an honest accident. According to a later recollection in the Winnipeg Free Press, Robinson was meant to be writing a story on the death of four hunters somewhere near Lake Winnipeg. The employee sending the telegraph however, made a mistake and wrote four hundred dead instead of four hunters. When other newspapers wrote back in a panic asking for further details, Robinson rolled with it and responded with a story of a steamship outing gone wrong. In Robinson’s tale, four hundred Icelandic picnickers had taken a steamer out onto the lake for a day only to perish when the boat sank. Fortunately it was completely untrue.

Most real shipwrecks in Manitoba tended to be less dramatic, and more importantly, less deadly. There are only a handful of accounts of truly disastrous shipwrecks, including that of the SS Princess which operated on Lake Winnipeg until it’s sinking in 1906. Sadly six people died in the accident.

Not all ships have such a sordid history. The S.S. Keenora, built in 1897, enjoyed many years as a freight and passenger ship in Lake Winnipeg and Lake of the Woods. In 1917, the SS Keenora was purchased by a syndicate of Winnipeg lawyers who used her as a floating dance hall. As well the SS Keenora is now at the Manitoba Marine Museum.

The SS Keenora sometime in the 1920s.

Source: Winnipeg in Focus

The more-remembered era of Winnipeg boating comes in the 1960s, as hauling freight by train and ship was on a steep decline. Winnipegger Ray Senft vacationed in Mexico in the early 1960s, where he saw Mississippi-style sternwheelers and was inspired to bring it home to Manitoba.

It took Senft and a team of workers just 80 days to build the M.S. Paddlewheel Queen in 1965. The total project cost $200,000. Similar passenger ships were built not long afterwards; Senft built a second ship, the Princess, in 1966, and in 1967 Dan Ritchie built the M.S. River Rouge. From the 1960s until 1993, Ritchie’s River Rouge and the Seft’s Paddlewheel were staunch rivals. There was at one point, five cruise ships travelling around Winnipeg and taking tourists to Lower Fort Garry and Selkirk. The companies merged in 1993 as interest in river tourism dwindled. Still, a number of celebrities took trips on these boats in their heyday. Among the well-known passengers were Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Kentucky Fried Chicken’s founder Colonel Sanders, and Guess Who front man Burton Cummings.

One by one, the cruise ships were sold, dismantled, or both across the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2013, the Paddlewheel Queen made its last voyage on the Red River and was then docked in Selkirk until it was heavily damaged by a fire in 2017.

You are unlikely to see steamboats or cruise ships traversing Winnipeg’s rivers these days, but if you visit the Forks in the summer you are likely to see canoes once again. Today, canoes are largely used for recreation and the majority of canoes are commercially manufactured, but there are new people out rediscovering the old art of birch bark canoe making. You may also see the water taxis running tours and ferrying passengers along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers.

Regardless of the means of travel, one thing remains true: Winnipeggers, past, present and future, will find ways to be out on the water.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Katie Dangerfield and Talia Ricci, The Sinking Tourism on Winnipeg's Rivers (Global News)

Paddlewheel Princess being cut up and sold for scrap (CBC News)

Ripple Steamboat, Manitoba Historical Society

Adrian Ames, Remembering the Riverboats (Manitoba Historical Society)

Bill Redekop, Paddlewheel Queens: Passenger ships once ruled the Red River (Winnipeg Free Press)

Rover Docks, Manitoba Historical Society

Alexander Docks, Manitoba Historical Society

Manitoba Prairie Steamboats: Ripple

Manitoba Prairie Steamboats: Bonnitoba

Hyland Park, Manitoba Historical Society

The Sinking of the SS Princess, Manitoba Historical Society