/ News

August 2, 2022

Commemorating Another Demolished Heritage Home

The 1932 James M. Gilchrist House at 1015 Wellington Crescent is being demolished. Without any legal safeguards provided by its inclusion on the City of Winnipeg’s Commemorative List of Historical Resource, the 90 year old house is simply being torn down after updating it was deemed too difficult and expensive. The second major historic home to be demolished on the street after the loss of 514 Wellington Crescent in November 2020, it highlights the lack of protection most residential built heritage is afforded in Winnipeg. It is another blow to the community’s rich history, environmental sustainability, sense of place and unique character, irreparably eroding the historic streetscape.

Under heritage conservation, the City of Winnipeg keeps three lists: the Nominated List of Historical Resources, the List of Historical Resources and the Commemorative List of Historical Resources. Although they all sound important, only buildings on the Nominated List of Historical Resources and the List of Historical Resources are protected from demolition or alteration of their character defining details. Being placed on the Commemorative List of Historical Resources protects nothing, instead the list serves to commemorate important heritage buildings that all too often end up being demolished. The Commemorative List was created after the City’s inventory of built heritage was done away with in 2014 as it was deemed illegal. Although the inventory provided no immediate protection either, it would have ensured there was a discussion about the heritage value of the home and if it was worth protecting before the house was demolished. At a time when other cities are eagerly compiling heritage inventories because they are seen as an important tool in conservation, it is disheartening that Winnipeg’s inventory was disbanded instead of adapted to make it both legal and functional. How can a city possibly save its built heritage when it does not even know what it has?

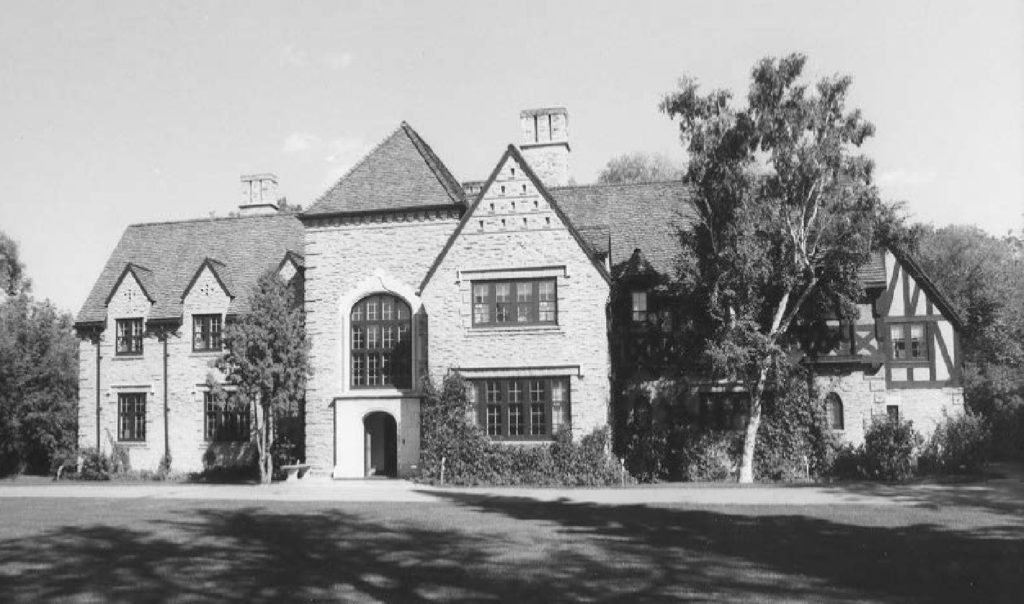

The house at 1015 Wellington Crescent was built for James M. Gilchrist, an American who worked in the Canadian grain industry. Designed by English architect Arthur Edward Cubbidge in the Tudor Revival style, the two storey home on the south banks of the Assiniboine River had plenty of space for Gilchritst’s wife, Florence, and their children. Although Cubbidge designed all types of buildings during his career, he is recorded as the architect for five homes on Wellington Crescent during the late 1902s and early 1930s, leaving his mark on the neighbourhood. Grand homes in Winnipeg from this period are far less common than their predecessors, constructed after the city’s boom period in the early 20th century and during the onset of the Great Depression, when wealth was growing scarce.

Inspired by Medieval English architecture, the Gilchrist House featured an engaging asymmetrical design with half timbering work, small turret details on the second storey, a grand chimney, detailed brick and stone work and a towering roofline. An excellent example of Tudor Revival, it would eventually be home to Gilbert McCrea Eaton, the grandson of Timothy Eaton of the famed T. Eaton Company. Later, respected Winnipeg lawyer and businessman, David Asper, would take up residence. Although the exertoir of the house appeared to be relatively unchanged over the decades, the interior was renovated by Asper.

In the final chapter of the Gilchrist House, it was determined that the thick stone walls that have stood tall for generations are now an impediment to modernization. With renovation costs and risks mounting, and no heritage designation to protect the house, it was decided that the house should be demolished and replaced instead of conserved. The design of the new house is intended to honour Gilchrist House and respect the historic streetscape, but the scale, materials, quality and history of the original home will never be matched.

While the City of Winnipeg has limited resources and cannot possibly protect every historic building within its bounds, mechanisms should be put in place to encourage conservation instead of helping perpetuate a disposable culture. Without demolition including the true cost of environmental harm it causes, people will always see it as the cheaper and easier option, instead of the default choice being to make use of the beautiful structure already standing. Unfortunately, future generations will have to pay the price for our shortsightedness, both in a lack of heritage and environmental degradation. When will enough heritage buildings be lost that we stop making meaningless lists and take action?

The front facade of 1015 Wellington Crescent in 1978.

Source: City of Winnipeg Report

What an enormous loss to Winnipeg. The T. Eaton mansion was the crowning jewel of Winnipeg real estate. Indeed it was a landmark that tourists needed to see to believe. To this day, I mourn its loss as I drive past the river lot that it graced. Of course, it boasted a circular driveway with enormous barred gates.

What a sad, tragic loss.