/ Blog

November 11, 2020

Valour: A Road to Remembrance

It was the war to end all wars. Unimaginable suffering and loss of life took place on both sides as the world descended into madness for four horrific years in the early 20th century. Young Canadian men in the prime of their lives were sent to the battlefield to take up arms. While those left behind were tasked with supporting the war effort and maintaining the home front with limited resources, never knowing when one of their loved ones would be lost. It was a time of great sacrifice and national unity, when differences were set aside to fight for the greater good, surely the last time that guns would be used in place of diplomacy. Amidst the carnage and senseless loss of life heroes emerged, brave and selfless souls, putting their lives on the line to help others without a second thought. As we pause on November 11, the 102 anniversary of the end of the First World War, these are the things we choose to remember. All the loved ones lost and wounded, all those who returned home with memories that weighed heavily on their hearts, and especially those that gave everything so that others might live in freedom. For their great valour when faced with insurmountable adversity will never be forgotten, forever enshrined on a street of a very grateful city!

Source: PastForward

Known as the Great War, The First World War started on July 28, 1914 when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Canada and Newfoundland were pulled into the war only weeks later when Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914. Although Canada was technically an independent country, Britain controlled its foreign affairs. Canada had some say over how much they wanted to be “in the war”, but they were for all intentions and purposes at war the moment Britain declared war. The battle lasted over four years, ultimately ending on November 11, 1918, when the Allied Powers defeated the Central Powers. Over 650,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders served during the war, and approximately 66,000 gave their lives while more than 172,000 were wounded.

In Winnipeg, it is almost impossible to estimate the number of Winnipeggers that served during the First World War and this is for a few reasons. Firstly Winnipeg’s geography is much larger today than it was in 1914. Many areas that are now part of Winnipeg, such as Charleswood and Transcona, were independent municipalities back then. Secondly, how does one define a Winnipegger? Was it someone who was born in Winnipeg, lived in Winnipeg, or enlisted in Winnipeg? It is estimated that over 1200 individuals made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives from what is modern day Winnipeg.

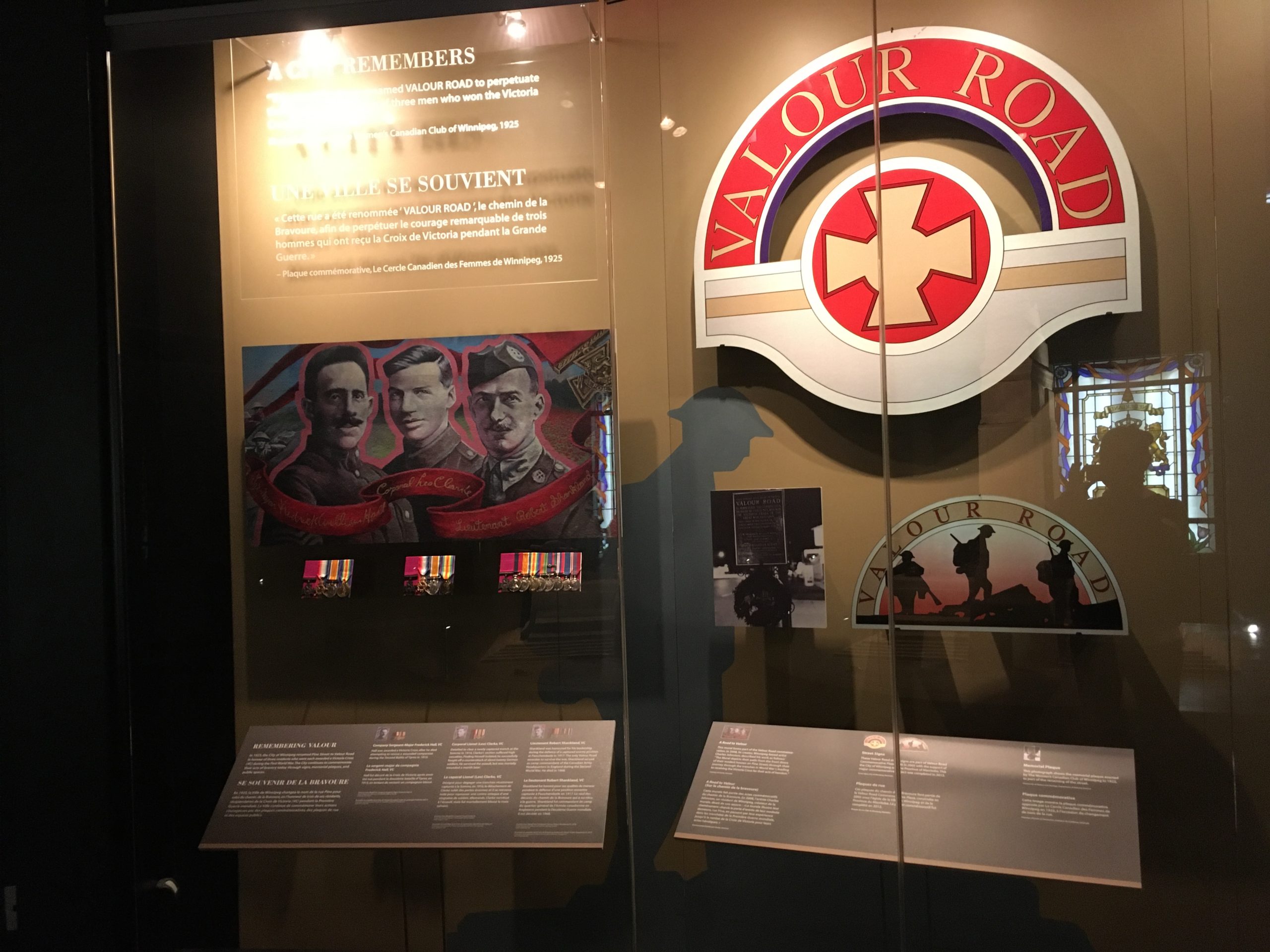

The Victoria Cross is the British Commonwealth’s highest medal awarded for bravery in battle. It was created in 1856 by Queen Victoria during the Crimea War. As of 2006 a total of 1352 people have been awarded the Victoria Cross. Although women are allowed to be awarded, so far all the medals have been award to male recipients. 94 Canadians have been awarded the Victorian Cross with the most recent ones being awarded in 1945. During the First World War, 13 Manitobans were award the Victoria Cross for their valour, and surprisingly three of these brave souls lived on the same block in Winnipeg, a strip of pavement then known as Pine Street.

Source: Rheanna C.

Captain Robert Shankland, who boarded with the Ritchie family at 733 Pine Street, served in the Canadian Infantry in the 43rd Battalion. Originally from Scotland, he came to Canada in roughly 1910, around the age of 23. He enlisted in Winnipeg on December 18, 1914 at the age of 27. His actions on October 26, 1916 in the Battle of Passchendaele were deemed worthy of a Victoria Cross. He was awarded the Victoria Cross exactly a year later on October 26, 1917. He was the only one of the Pine Street trio to survive the Great War and to be awarded the Victoria Cross in person. He served in a non-combat role during the Second World War, as he was deemed too old at the age of 53 for combat. He passed away on January 20, 1968 at the age of 80 and is buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Company Sergeant Major Frederick William Hall lived at 772 Pine Street. He served in the Canadian Infantry in the 8th Battalion. Originally from Ireland, he came to Canada with in family in roughly 1910 around the age of 25. He enlisted in Valcartier, Québec on September 26, 1914 at the age of 29. Due to his enlistment in Québec, there is some speculation if he actually lived on Pine Street, but evidence points to him living there briefly but moved before the war broke out. He was killed in action on April 24/25, 1915 at the age of 28 during the 2nd Battle of Ypres. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross on June 23, 1915. He is commemorated at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium (panel 24-26-30).

Corporal Lionel “Leo” Beaumaurice Clarke lived at 785 Pine Street. He served in the Canadian Infantry in the 2nd Battalion. Although born in Hamilton, Ontario, his family’s home was on Pine Street. He enlisted in Winnipeg on February 2, 1915 at the age of 22. He fought in the Battle of the Somme and on September 9, 1916, where he successfully defended a trench alone. It was this action for which he was nominated for a Victoria Cross. Weeks later in a bombing, he was severely injured and died from spinal injuries on October 19, 1916 at the age of 23. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross on October 26, 1916. He is buried at plot II.C. 3A. in the Etretat Churchyard in France.

Clarke’s, Hall’s, and Shankland’s medals are now permanently on display in the the Royal Canadian Legion Hall of Honour at the Canadian War Museum located in Ottawa. The medals were acquired by the War Museum in 2009 (Shankland), 2010 (Clarke), and 2012 (Hall). The medals returned home to Winnipeg for a visit in 2014, when they were displayed at the Manitoba Museum in an exhibition commemorating the role of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders regiments during the First World War.

There is an urban legend that these three men went to high school together. Unfortunately, this is not true. Having a high school education was uncommon during that time especially for the working class. Most boys during that time period left school after completing the eighth grade which would be roughly 13/14 years old. Clarke was four years younger than the other two men and he is also the only native Winnipegger of the trio. Hall immigrated to Canada from Ireland when he was 25 years old and Shankland from Scotland when he was 23 years old. Simply put, it is impossible that these three men went to high school together.

In June 1925 there was a petition to have Pine Street renamed Valour Road because of the brave actions of the three men that once lived there. The Women’s Canadian Club and the Issac Brock Community Club went about this petition jointly. The petition was successful and on November 11, 1925 Pine Street was officially renamed Valour Road. However this was not without some controversy. Some people thought renaming the street after a war, glamorized war and sent the wrong message. Valour Road is likely the block with the most connections to the Victoria Cross recipients within the British Commonwealth.

There are three memorials on Valour Road, although none are on the lone block where the three men lived. The first one is the golden light post and plaque located at the corner of Portage and Valour that was unveiled in 1925 when the street was renamed. The second is the mural painted by Charlie Johnston in 2008 at the corner of Ellice and Valour. The third and most recognized memorial for the three soldiers is Valour Road Plaza which is roughly a kilometer north of the block where the men lived. This memorial erected in 2005 was originally just a steel sculpture of the three men’s silhouettes. However in spring of 2012 plaques were unveiled adding to the memorial. The individual homes do not have any acknowledgement of the men that lived there, whom the street was named in honour of. There is no evidence that indicates that the block has been renumbered anytime in its history, so it is very likely that the locations are true. However, it is not known if the homes are the same ones from before the First World War? The homes themselves are very likely pre-Second World War, but how old they are exactly are a mystery. It does not matter if the homes are original, all that matters is that these three braves souls risked their lives, with two giving the ultimate sacrifice to defend our freedom.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Rheanna Costen on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Commonwealth War Grave Commission

"The Cost of Canada’s War" | Canadian War Museum / Le Musée Canadien de la Guerre

"Enlist! New Names in Canadian History : recruitment campaign" | Library and Archives Canada

"Etretat Churchyard" | World War One Cemeteries

Front Page | Manitoba Free Press - August 5, 1914

General Solider Search | Canadian Great War Project

"Heritage Minutes: Valour Road" | Historica Canada

"November to Remember " | Winnipeg School Division

"Petition Asks Name Changed to "Valor Road"" | Winnipeg Tribune - June 25, 1925, Page 3.

The Royal Canadian Legion Hall of Honour | Canadian War Museum / Le Musée Canadien de la Guerre

"Valour Reunited" | Winnipeg Free Press - November 10, 2012, Page 6.

Victoria Cross Recipients | Government of Canada

I know that the caption says “The 34th Fort Garry Horse regiment parade down Portage Avenue in Winnipeg before leaving to fight in the First World War in 1914.”, but The FGH never wore kilts.

Maybe they’re back behind the brass band ? The young guys at the front in their kilts and hair sporrans are almost certainly from The Winnipeg Highland Cadet Corps. They look far too young to be guys from the Cameron contingent of the 16th Bn, or 43rd Battalion Camerons, CEF.