/ Blog

October 24, 2019

The Watcher Among The Graves: St. John’s Cemetery

Passing by St. John’s Cemetery today, you would be hard pressed to find anything out of the ordinary. It is a small, well-treed cemetery, next to St. John’s Anglican Church (158 Anderson Avenue)– an assortment of headstones, large, small and everything in between cover the grounds.

What you cannot tell from simply passing by, is that inside the cemetery you can find the final resting places of some of early Winnipeg’s most prominent citizens.

St. John’s in the oldest Anglican Parish in western Canada, founded in 1820 by Reverend John West, when he arrived to serve as Chaplain to the Hudson’s Bay Company. Their first church was erected on the lot in 1822, the first of four churches to be constructed for the Anglican Church.

St. John’s Cemetery in mid-October, 2019.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

The cemetery is, in fact, older than the church itself – predating the parish by about 8 years. It was established by the Selkirk Settlers, sometime after their arrival to the area in 1812. Few records remain about these early burials, however, the first known burial to take place was in 1821, with the funeral of 84-year-old John Bruce.

Tracking down these grave markers, and grave sites, has proven to be difficult. The earliest grave markers used would have been constructed with wood, which is hardly the most permanent material, and the 1826 flood would washed away any trace of the earliest burials to take place here at the site.

The oldest existing grave markers date back to the 1830s, to infants David Lloyd Jones (d.1830) and George Simpson (d.1830). David Lloyd Jones was the child of Mary Jones, the wife of Reverend David Jones. She dedicated much of her time to the Red River Academy – the first Ladies College in Western Canada. As an advocate for women’s education in the colony, Jones taught at the school until her death in 1836. She would be buried next to her son at St. John’s. Her students donated a plaque in her memory which can be found inside the Cathedral.

Walking tour maps can guide guests through the who’s who of Manitoban’s buried at St. John’s. Some of the figures here have more polarizing legacies than others.

John Christian Schultz, who was buried here in 1896, was a staunch political rival of Louis Riel. Vocally opposing Riel’s government in the Nor’Western paper, which Schultz owned, he worked to incite anger both in the province and in Eastern Canada against Riel. Though Schultz seemed to have softened some in his later years, he was not well liked in the colony. Upon seeing the inscription on his tombstone, Sheriff Colin Inkster allegedly remarked: “What a pity we knew him.”

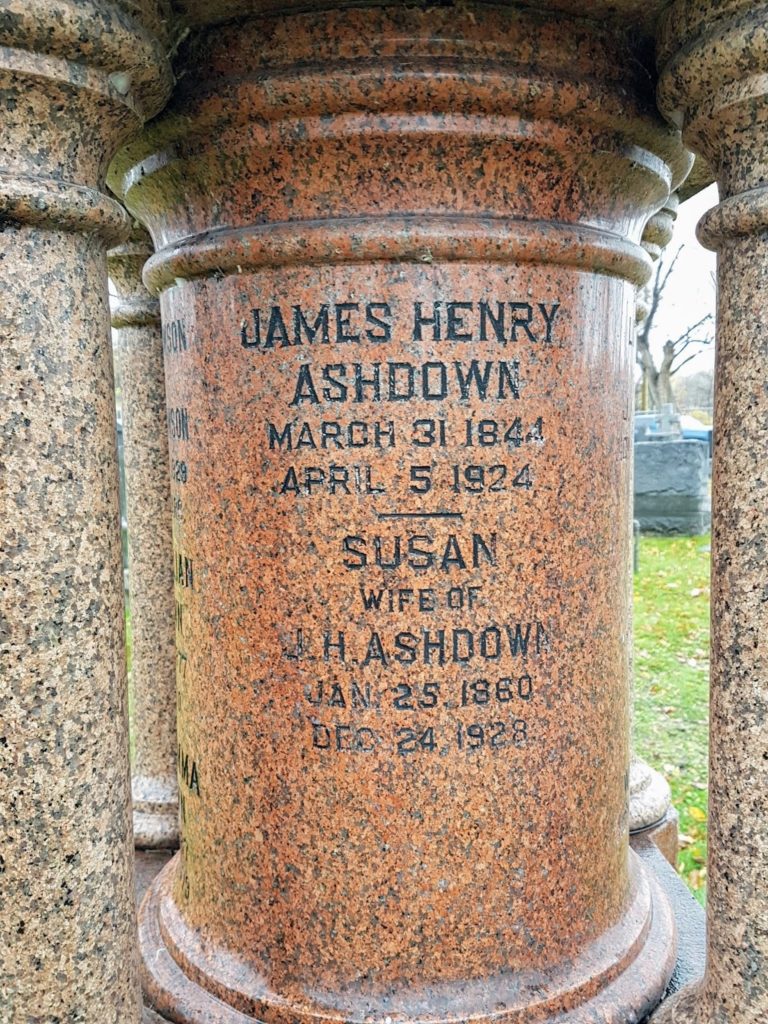

Many of Winnipeg’s elite would have had their families and estates to pay for their grand grave markers. James Henry Ashdown, Winnipeg’s “Merchant Prince” and head of a massive hardware empire, has one of the tallest and grandest headstones in the cemetery – which makes sense, given that Ashdown was one of Winnipeg’s wealthiest men and one of it’s first millionaires.

The headstone for the Ashdown Family stands out among the shorter headstones surrounding it.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

A close up of the inscription on the Ashdown’s headstone. It reads:

March 31 1844

APRIL 5 1924 –

—

SUSAN

WIFE OF

J.H. ASHDOWN

Jan 25 1860

Dec 24 1928

The patriarch of Winnipeg’s Richardson family, James Richardson, is buried here too, in a similarly distinguished family plot.

The Richardson Family Plot.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Others though, did not have the funds to pay for an expensive headstone. Many families could afford little more than a block of stone with the name, birth and death dates for the deceased – as between the funeral and material costs it could and often did add up quite quickly.

An example of a more modest, and affordable headstone.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg.

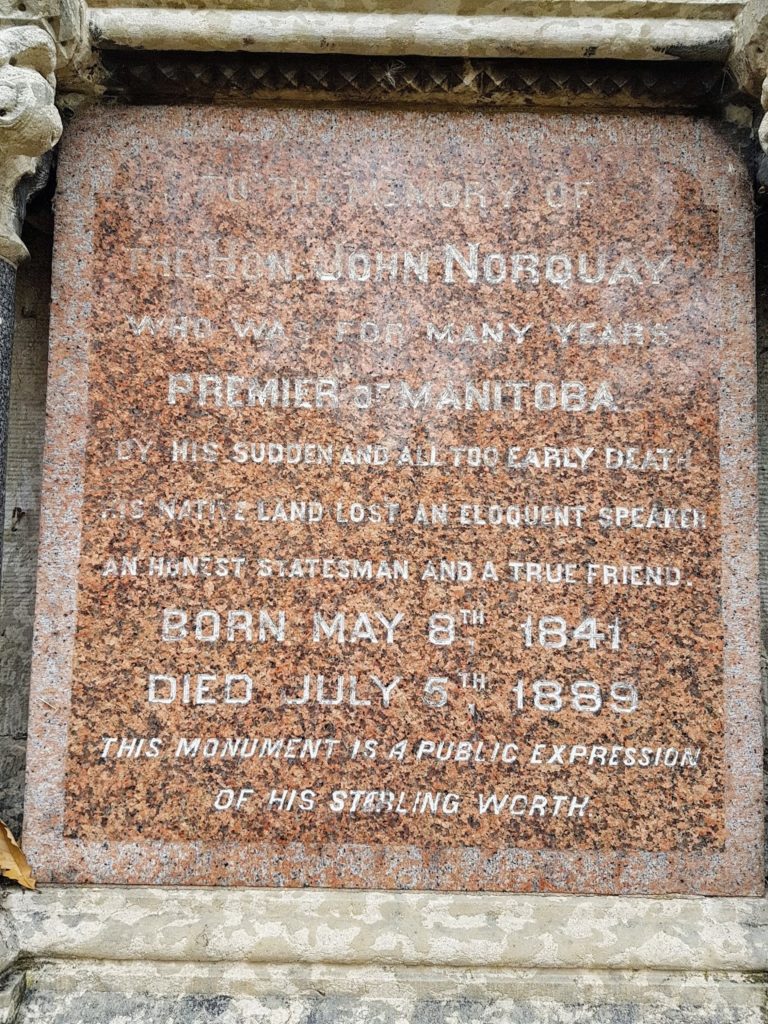

John Norquay was Manitoba’s first local Premier. His predecessors for the job were all immigrants from England, but Norquay was born in St. Andrews, Manitoba, and was Anglo-Metis. Known as one of Manitoba’s finest speakers, Norquay was fluent in six languages and was a well-liked politician. He served as Premier in 1878-1879, and helped found the Manitoba Historical Society. Despite all of this, Norquay’s family was not well off financially, and the job of Premier did not pay particularly well. After Norquay passed away unexpectedly in 1889, the community raised the funds to pay for his tombstone. Contributions were limited to just $1, so that everyone could contribute. Ultimately, the $1700 monument would be designed by future Provincial Architect Samuel Hooper and David Ede.

John Norquay’s Monument, paid for by members of the community.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

A close up of the inscription on Norquay’s monument. It reads:

Who was for many years Premier of Manitoba.

By his sudden and all too early death

His native land lost an eloquent speaker

An honest statesman and a true friend.

Born May 8, 1841, Died July 5 1889.

This monument is a public expression of his sterling worth.

Part of the Manitoba Coat of Arms is carved into tyndall stone atop the inscription on Norquay’s Monument.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

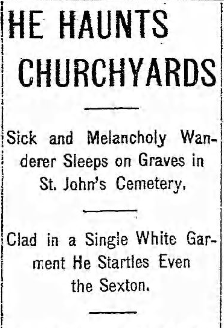

Tales of ghostly apparitions and hauntings often go hand-in-hand with cemeteries, and St. John’s Cemetery is no exception.

Rumours began to swirl in Winnipeg that the burial ground was haunted when the Winnipeg Telegram reported that a ghostly figure dressed in white undergarments had been seen wandering the cemetery late at night on September 11th, 1903.

The story gained traction quickly. Superstition was commonplace in Winnipeg, and much of North America, at the time. Seances and psychics were a flourishing industry at the time. Then, understandably the rumours of the ghost captured the publics’ imagination. Those at St. John’s Parish purportedly began greeting each other with “Have you heard anything new about the watcher among the graves?”

Not all were swept up by the accounts. The church sexton, William Binzier, expressed doubts early on about the accuracy of these accounts, though few appeared to listen to him.

When the rumours had gotten out of hand, Binzier planned a stake out. Hiding in the bushes of the cemetery late one evening, Binzier would wait to see if he, too, would be visited by a ghostly apparition. None came.

Instead, Binzier would catch sight of a very human figure standing near a grave stone. Binzier confronted the man, who was dressed in white undergarments, and ask what he was doing.

“I have no place to sleep and am too sick to work,” the man replied, “so I brought my blankets here to lie in peace.”

Binzier ushered the man, and his camping gear, away from the cemetery to a nearby park and the haunting of St. John’s Cemetery promptly ended.

The headline for the Winnipeg Telegram’s article on the alleged haunting.

Source: Winnipeg Telegram, 1903-09-11 (7)

Over the course of the 20th century, many of Manitoba’s earliest pioneers would be buried at St. John’s Cemetery. Among them, Margaret Scott, founder of Margaret Scott Mission, and Sam Steele, a famous RCMP Officer and soldier who was given his own Heritage Minute.

Today, St. John’s Anglican Church is still an active part of the community and the cemetery is well-maintained. Each year members of the congregation plant flowers on select graves – funds raised through this process go towards both the planting of flowers, and the towards the maintenance of the church grounds.

There is more to heritage than just buildings. Memorials, landscapes, and geography also give us a sense of our history and the world around us. Cemeteries and the monuments that lie within, tell us about how settler societies memorialize the life of those we have lost, and of the supernatural trends that once captured the public’s imagination.

SOURCES:

City of Winnipeg Historic Buildings Report

St. John’s Anglican Church

Manitoba Historical Society

Spectre Alleged to Haunt St. John’s Cemetery, Winnipeg Real Estate News.

Heritage Winnipeg

Winnipeg Telegram

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.