/ Blog

April 1, 2020

The Promise of Our Lady of the Good Heart

There is a small chapel in a park across the street from the church of St. Norbert’s Parish, at 80 Rue St. Pierre. It has no door, only a small iron-wrought fence. A statue of the Virgin Mary watches over the space from her place at the rear of the sanctuary. This small chapel, named La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secour (or, Our Lady of the Good Heart), dates back to 1875 and represents a promise kept to the St. Norbert Community.

St. Norbert, at the time, was a small French-Catholic community made up prominently of Métis farm families. It had been this way since the 1820s, when the merger of the Northwest Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) left many unemployed. As early as the 1830s, the HBC’s census recorded at least 72 heads of family in St. Norbert. Heads of families in this case meant men, so we do not know the exact number of women and children present in the settlement. Regardless, the growing population caught the eye of the Grey Nuns in St. Boniface, who began sending Sister Eulalie Lagrave to St. Norbert to teach in 1844. By 1856 there was a demand for a permanent church, and one was quickly built. Within a year of the construction of the the new parish church, Archbishop Tache in St. Boniface formally created the Parish of St. Norbert.

|

| Archbishop Tache, seen here in 1890. Source: Provincial Archives of Manitoba |

Meanwhile, in Eastern Canada, the recently ordained Noël-Joseph Ritchot was serving at a mission in rural Quebec (then known as Lower Canada). Ritchot, born in 1825, had spent much of his early life working on a farm and had begun studying for the priesthood in 1844. While at the mission in Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, Ritchot made the decision to go west and work under Archbishop Tache. Ritchot made the journey to St. Boniface in 1862, and was quickly placed with the St. Norbert Parish.

It did not take long for Ritchot to earn the trust of his parishioners, and the title of “Father”. Much of his time was spent socializing with them and working to understand the communities needs. Ritchot was even invited to participate in bison hunts, though hunts were occurring less and less as the bison were overhunted across the prairies.

Things began to change in the community by the late 1860s. The Dominion of Canada was formed in 1867, and the Canadian government set it’s sights westward. The fur trade, once a prominent part of the Western Canadian economy, was no longer as lucrative as it once was. The HBC, as such, was looking to strike a deal to sell Rupertsland to Canada.

While this was an enticing idea for some living in Rupertsland, it raised concerns for many others. The French, Métis, and Indigenous communities were rightfully worried that should Rupertsland join confederation, their language and culture would not be respected or protected. It would seem these concerns were validated when the Canadian Government purchased Rupertsland and quickly appointed an English speaking governor who held no ties to the French or Métis.

The new governor, William McDougall, sent men out to survey Rupertsland in 1869 with a plan to redivide the land into new plots for English settlement. Many of the Métis families in St. Norbert and other communities did not hold legal title to their land, and the prospect of losing their homes became startling real. In July of 1869, a group of concerned citizens gathered at the St. Norbert Church to discuss their options; among the crowd was the one and only Louis Riel. Riel, at this point, had only recently returned from his studies in Quebec but found himself quickly thrust into political turmoil in Manitoba. Father Ritchot helped play host to the meetings at the St. Norbert Church, inviting prominent speakers and even billeting Métis men in his own home. On October 19th, 1869, the Comité national des Métis was formed in the St. Norbert Church, and Riel was appointed secretary of the group.

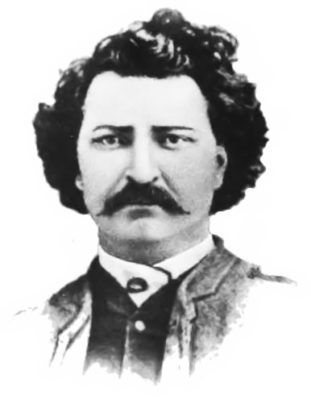

|

| Louis Riel (1844-1885) in 1884. Source: Province of Manitoba Archives. |

Land surveyors continued to come, to plant stakes in the ground for future development. Riel and others would wait until the surveyors had left, then remove the stakes. Though no genuine confrontation had occurred yet, Ritchot was worried about the possibility of bloodshed between the land surveyors and his parishioners. Ritchot made his parish a promise: If this conflict was resolved without bloodshed, he would construct a new chapel.

This promise was put to the test when, on October 20th, word reached St. Norbert that Governor McDougall was due to arrive in St. Norbert – and he wasn’t coming alone. With him, Governor McDougall was bringing both weapons and men. Riel quickly organized the construction of a wooden barricade (la barriere) along the main road.

Governor McDougall reached St. Norbert on November 2nd, only to be met by the barricade, Riel, and 40 other armed men. Surprisingly, Governor McDougall did not force the issue, and was escorted out of the settlement without force. He and his men returned to Ottawa.

This was the inciting incident to what is now known as the Red River Rebellion. Shortly after Governor McDougall left Riel led a group of men to overtake Upper Fort Garry and established a provisional government in an attempt to negotiate terms before Rupertsland would join confederation. It is a familiar story in Manitoba history, and you can read more about it here. Ultimately Rupertsland joined confederation in 1870 and became the Province of Manitoba.

As the initial confrontation had avoided bloodshed, the Parish of St. Norbert had kept their promise. While Ritchot may have had every intention of fulfilling his side of the bargain, circumstances prevented him from doing so immediately. In February 1870, Ritchot was appointed as a delegate to the Canadian Government and ventured to Ottawa. As a delegate, Ritchot fought to secure bilingual and bicultural institutions in Manitoba. He would also secure 1,400,00 acres of land for the Métis in Manitoba. These negotiations culminated in the creation of the Manitoba Act. After five months in Ottawa, Ritchot was able to return home on June 24th 1870. Yet, after the signing of the Manitoba Act, it became clear that the Canadian government did not intend on keeping some of the promises they’d made, and Ritchot returned to Ottawa several more times throughout the 1870s in an attempt to renegotiate.

It took until 1875 before Ritchot was able to complete his promise. With the help of his parishioners, Ritchot designed and built a lovely outdoor chapel. In the late 1800s, open-air chapels were a common enough amenity though few remain now. Ritchot dedicated the new chapel to the Virgin Mary and today, Ritchot’s chapel is the last of its kind in Winnipeg.

The chapel, painted white with blue trim, has a gable roof with simple wooden siding. Multi-coloured glass panels line the arched windows on the chapels walls. Small wooden pews face the back of the sanctuary, where a statue of the Virgin Mary rests in an alcove. Below her is an intricately carved and colourful tabernacle. The interior walls are covered in wooden wainscoting and white stucco. Above, biblical murals cover the coffered ceiling. These murals, painted by German artist Constatin Taufenbach, depict various stages of the Virgin Mary’s life and were installed in the chapel in 1885.

Not much has changed in the chapel over the years. Iron-wrought gates still protect the sanctuary, and it still sits facing the parish church. In 1989, it was designated as a Provincial Heritage Building by the Government of Manitoba. The ceiling panels were removed and installed in the nearby in 1994, a means of preserving them for future generations.

Artist Robert Freynet was hired to replicate Taufenbach’s murals, which Freynet claimed was no easy task. Tauffenbach came from the German Romantic school of art at and painted “spontaneously and confidently”. To get into the proper state of mind, Freynet reportedly used both prayer and meditation. The project cost $60,000 and Freynet’s replicas were installed on May 31st 1994.

In 2003, the chapel underwent minor restorations as part of the Prairie Churches Project. Meant to identify and restore distinctive churches in Manitoba, this project was funded by the Thomas Sill Foundation, the J.M. Kaplan Fund in New York, and the Province of Manitoba.

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secour may be just a small wooden chapel in St. Norbert, but it is tied to the much larger history of Manitoba.

SOURCES:

Stained Glass Institute of Canada

Constatin Taufenbach Portraits | Centre Du Patrimonie

Our History | St. Norbert Parish

Constantin Taufenbach | Manitoba Historical Society

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bons-Secours | Historic Places Canada

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bons-Secours | Province of Manitoba

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secours | Heritage St. Norbert

St. Norbert | Wikipedia

Father Noel Joseph Ritchot | Heritage St. Norbert

Father Noel Joseph Ritchot | Dictionary of Canadian Biography

La Barriere | Heritage St. Norbert

La Chapelle de Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Secours | Manitoba Historical Society

Winnipeg Free Press, 1994-05-24 (13)

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.