/ Blog

June 5, 2020

The Forks Market: Adaptive Masterclass

At the heart of Winnipeg lies the Forks, a bustling public centre with diverse food, activities, performances, shops, history and more. The site is located where the Red and Assiniboine Rivers meet, an historic waterfront framed by the rail line. As Winnipeg’s most popular tourist attraction it welcomes more than four million visitors on an annual basis. It is a community gathering place that includes an amphitheatre, boat dock, heritage adventure playground, interpretive area, museums, river walk and the iconic Forks Market. With its incredible food, shops and entertainment, the Market was a visionary project that successfully breathed new life into historic spaces. Though the Market is just over 30 years old, the buildings it is in have stood for over 100 years, on land that has witnessed thousands of years of history, from the early Indigenous settlement, to the fur trade, the Industrial Age, and more!

Human activity at the Forks dates back to around 4,000 BCE when the site’s strategic location was fundamental to the people that lived in that area. Starting in 1989 archeologists have been uncovering evidence of Indigenous people living on the site, with bison hunters camps dating from approximately 6,000 years ago! People also used the location as a meeting place, fishing camp and settlement. Among the archeological finds was a 6,000-year-old hearth, catfish bones, stone tool flakes and later campsites. These materials provide physical evidence that the Forks and Winnipeg are built on the land of the Ojibwe, Cree, Oji-Cree, Assiniboine, and Dakota peoples. The Forks continued to be home to these Indigenous people through the 18th century, used as a location for their seasonal camps. The Forks is also the birthplace of the Métis Nation.

When the fur trade started in Canada in the 17th century, the Forks quickly became an important location for Europeans. Long before trains, planes and automobiles were used or even invented, boats were the main mode of transportation in western Canada. With two major rivers used by fur traders converging at the Forks, trading posts, known as forts, soon appeared, with competing companies trying to assert their dominance. First was Fort Rouge, built in 1738, by which time the area was already known as the Forks. Fort Gibraltar was established in 1809, Fort Douglas in 1812, Fort Garry in 1822, all interspersed with numerous other short-lived forts, largely forgotten over the passage of time. People and goods arrived and departed by way of the river, settlements were built, and the site became a large informal market place.

By the middle of the 1800s, the fur trade was waning and although the Hudson’s Bay Company still owned the Forks, it was now being used for farming. As immigration to the prairies increased, two immigration sheds were built at the Forks, where those travelling from the United States could pick up their land grant before continuing west. The transcontinental railway opted not to pass through the Forks when it arrived in Winnipeg in 1881 but the 465-acre site was purchased by the Northern Pacific Railway and Manitoba Railway in the mid-1880s.

The two railways intended to develop extensive infrastructure for repairs, passengers and freight that could easily connect with waterborne transportation, focusing on rail routes to the United States. This did not quite go as planned, with Winnipeg’s center of commerce shifting away from the Forks and towards Portage Avenue. Nonetheless, the rail yards were built, and at the beginning of 1886, the Forks emerged as one of the key sites of early railroad development on the prairies. In 1892 a grand hotel, the Manitoba, built by the railways, was opened to service the site. Located at the southeast corner of Main Street and Water Avenue, it lasted just over nine years, burning down on February 8, 1889. The future of the Forks was then cemented as an industrial site, crisscrossed by tracks and scattered with unfriendly buildings, cutting off all public access to the shoreline. The closest the public could come would be Union Station, a passenger terminal at 123 Main Street, which opened in 1911. Many of the buildings at the Forks today date back to this period of early development.

The Manitoba Hotel in 1899.

Source: Virtual Heritage Winnipeg

Railways came and went, with the Canadian Northern Railway, the Grand Trunk Pacific and then the Canadian National Railway (CN) using the site, known as the East Yards. By the 1960s, trucks were taking the place of trains and CN was moving its operation to more affordable areas of the city. Only using the East Yards at 25% of their capacity, CN was looking for a buyer by 1973. At the same time, Winnipeg was re-evaluating its inner-city, left neglected after the great exodus to the suburbs following the second World War. The riverbank had become an industrial wasteland, not desirable for people or flora or fauna. Winnipeg’s eventual solution was the Core Area Initiative. Established in 1981, it became “one of Canada’s largest urban regeneration efforts” (MAID), which saw all three levels of government come together for 11 years to spend $196 million on “social economic and physical renewal of Winnipeg inner city” (MAID). A project of the Core Area Initiative was the Forks Renewal Company, established in 1987, “to provide a mechanism for implementing the redevelopment of the former CN East Yards area through a combination of investments by the Corporation, the private sector, institutions, and governments” (The Forks). This further built on the 1974 designation of the Forks as a National Historic Site of Canada, recognizing its importance as a historic meeting place where thousands of years of history had taken place.

The Forks Renewal Company wasted no time, with $20 million to redevelop the site, they purchased the 36 hectares East Yards in 1987. The next year an all-volunteer Heritage Advisory Committee for the site was formed to provide heritage advice for the Forks. This advice was then applied through The Forks Heritage Interpretive Plan. Its goals were:

To identify, preserve, and protect heritage resources at The Forks, to promote interpretation of heritage resources at The Forks, and to encourage community participation in development and operation of heritage interpretive programming at The Forks.

The first two projects undertaken at the Forks were the Forks National Historic Site (a national park) and the Forks Market. The Forks Market made use of two historic railway buildings, the 1908 stables of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway and the Great Northern Railway. The stables had originally been used to house horses that the railways used to deliver express fright from the East Yards to homes. The two buildings, located about 10 meters apart, had been repurposed over time, with one eventually functioning as a garage and the other as an employee gym, complete with an indoor track. The two-storey buff brick buildings featured minimal ornamentation and provided a blank canvas for redevelopment.

In addition to the potential afforded by such an expanse of riverfront property, there was a sense of reclamation. The epicentre of this city’s initial growth, and a meeting place for many years before that, the river junction was an invaluable historical site, made inaccessible by industrial development.

Winnipeg Free Press, Public Market central to renewal at Forks

Randal McIlroy, June 10, 1989, page 117

To create the Forks Market, the two former stables were connected by a glass and steel atrium, creating 462,680 square feet of space. Bricks from the buildings were saved and cleaned by hand so that they could be reused in the Market, preventing waste and ensuring historical continuity. At the east end of the atrium a six-storey glass and steel tower was built, complete with an elevator and observation deck, providing outstanding views of the two rivers. The Market was based on Vancouver’s Granville Island Market and Toronto’s St. Lawrence Market, with a heavy emphasis on it not being just another shopping mall. The interior design of the Market celebrated its industrial history, an open concept that exposed the existing brick and steel. The plan was for there to be a food market, arts and crafts market, restaurants and cafes, live entertainment and office space, all opening for the summer of 1989.

Although the National Historic Site opened in time for summer, the Market did not officially open until October 5, 1989. Located at 1 Forks Market Road, work was still being done on opening day with only about 60% of the stalls for vendors under contract. Compliance with the health code caused delays, with the rustic interior of the Market not suitable for food services. Two butchers, a seafood shop, a fine Italian pastry shop and a bakery were the only permanent tenants ready for opening. The Royal Dance Conservatory was the first major tenant to take up residence, operating out of two studios on the second floor. The Conservatory blossomed after moving to the Market and credited its new location for the increase in business, which offered free parking, shopping and dining. The Market would offer 1000 free parking spots, an offer that no true Winnipegger could resist. Eventually costing $7.1 million to complete, even in the rain the Market enjoyed a successful opening day, expecting 10,000 people to attend.

Despite a large turnout for its opening, the Market was not without its problems. Many were cynical that anyone would visit the Market beyond its opening day. Construction would not be completed until 1990. Over 300 people applied for the anticipated 55-60 vendors stalls, but it was a struggle to fill the 25 that were actually available. Some complained that rent was too high, while the Forks said most of the applicants were not in keeping with the concept of “unique specialty shops”. Fast food companies were not welcome and homemade food was not prohibited by the health code. Some vendors had exclusive rights on the sale of specific foods, leaving no room for other vendors with similar wares. Despite these obstacles, the Forks stuck to its vision, with the site going from obscurity to popular tourist destination.

All around the Market, development continued. The former National Cartage Building became the Johnston Terminal, filled with shops, restaurants and office space. The Children’s Museum resides in the former Northern Pacific Railway and Manitoba Railway’s Buildings and Structures Building. The CN Steam Generating Plant and Powerhouse became the CityTV office and studios. New buildings and landscaping made the Forks a beautiful and desirable location. All the while Union Station, which was built and designed by Warren and Wetmore Architects (who also designed the Grand Central Station in New York) is still in operation as the railway’s passenger terminal to this day.

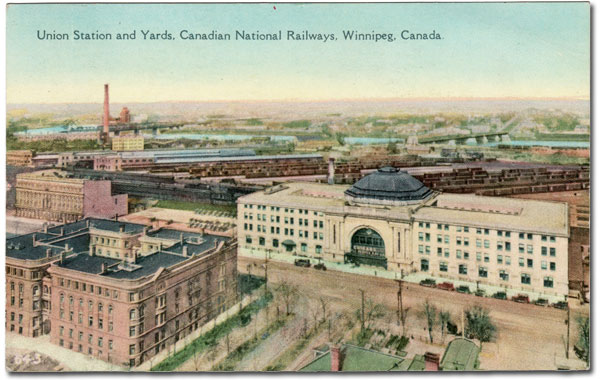

Union Station with the East Yards in the background, from the 1920s.

Source: Rob McInnes, WP0634

Twenty five years after opening, the Forks Market had very much succeeded, but it was due for a refresh, with the most common criticism being that nothing had changed since its original inception. It was finally conceded that the original vision for the Market, being similar to that of Vancouver or Toronto, did not work out. This was not because the Market had done something wrong, but because the original plan called for 1000 to 1500 housing units to be built at the Forks with in five years of the start of the project. This would have created a lively community to frequent the Market on a daily bases, making it a viable community shopping centre. The Forks has not given up on this dream, for in 2013 work began on creating a long term vision for the Railside lands, which would see the two largest parking lots at the Forks developed into both residential and commercial space. But good planning takes time, and as of 2020 there is still no housing at the Forks.

But housing or not, the Market must continue to grow and adapt with the city to remain vibrant. In 2014 Number TEN Architectural Group was hired to reimagine the central court in the atrium of the Market as a food hall, replacing the Forks’ signature teal colour scheme with new materials that speak to the buildings’ industrial past. A mix of natural wood, hand wrought metal and brick was used to create a seamless blend of old and new, with exposed c-channels and i-beams acting as a visual connection to the site’s railroad history. Circular seats that swing out from underneath tables are a nod to factory furnishings, while a vast new oak harvest table that can seat up to 80 people resonates with the Forks’ theme as a meeting place. New lighting and new food offerings completed the makeover, rebranding the Forks Market as a hip and desirable dining and shopping experience for tourist and locals alike.

The success of the Market is further bolster by the success of its surroundings, with people from all walks of life drawn to the Forks many events. These events include Winnipeg Pride, the Winnipeg International Children’s Festival, Nuit Blanche, and Heritage Winnipeg’s own Doors Open Winnipeg! Winter months bring skating trails, the Forks’ famous Warming Huts, winter cycling, a holiday bazaar and hot cocoa to to sip on while you warm up inside the Market. No matter what the season, there is always something new to see at the Forks as they continuously find innovative ways to bring people together. Through this range of diverse offerings, the Forks has transformed from traditional meeting place, to industrial wasteland and back to celebrated meeting place, reflecting our city’s dynamic culture and history through its continued growth and reinvention. And the Forks Market was the ambitious adaptive reuse project that started it all, bringing together recreation and conservation in an exquisite celebration of community and heritage, to be savored by all for years to come!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Georgia Wiebe and staff on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

ArchDaily, The Forks Market Food Hall / Number TEN Architectural Group

Canada’s Historic Places, The Forks National Historic Site of Canada,

Canada.ca, The Forks National Historic Site of Canada,

Canadian Encyclopedia, Fur Trade in Canada

CBC, More changes coming to The Forks as long-term leases end, CEO says

City of Winnipeg, Timeline of Winnipeg Historical Events 1670-2012

Claire Elizabeth Campbell, Nature, Place, and Story: Rethinking Historic Sites in Canada

Douglas Archives, Fort Douglas, Canada

Forks North Portage Partnership, Railside at the Forks

The Forks, The Forks North Portage Partnership

Manitoba Historical Society, Introduction: Focus on The Forks,

Manitoba Historical Society, The Old Forts of Winnipeg, 1738-1927

Mennonite Archival Image Database, Core Area Initiative (Winnipeg, Manitoba)

Number TEN Architectural Group, A new vision for The Forks Market

Number TEN Architectural Group, The Forks Market Refresh,

Parks Canada, The Forks National Historic Site,

The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Forks,

The Forks, Celebrating 25 years,

The Forks North Portage Partnership, 2009 Annual Report,

The Forks, The Forks Heritage Interpretive Plan (1993),

Winnipeg Free Press, Children dance happily to tune of work drills, October 4, 1989, page 30

Winnipeg Free Press, GM foresees warm reception, first-weekend crowd of 10,000 October 4, 1989, page36

Winnipeg Free Press, Market crowd enthusiastic By Aldo Santin, October 6, 1989, page 1

Winnipeg Free Press, Market right on track blending new, old By Randal McIlroy, October 4, 1989, page 28

Winnipeg Free Press, Public Market central to renewal at Forks by Randal McIlroy, June 10, 1989, page 117

Winnipeg Free Press, Trouble at the Forks By Alice Krueger, September 20, 1989, page 41

Winnipeg Free Press, What went around came around

Winnipeg Free Press, When will Forks market open? By Manfred Jager, August 25, 1988, page 21

Winnipeg Free Press, Why was horse barn in rail yard? By Manfred Jager, October 18, 1989, page 38

Available to all Winnipeggers, Chair Your Idea is a crowdsourced and crowdfunded open competition that seeks to generate 1000+ urban design ideas and $30,000+ to realize the winning idea. For a $25 registration fee, participants were asked to submit their creative initiative in 140 characters or less and contribute one white chair for public use to mark their submission. The chairs, with the ideas written on them, were placed in public locations throughout the city and cared for by participating local businesses for the duration of the three week competition period. The accumulating chairs and the creative ideas associated with them allowed Winnipeggers to enjoy newly claimed public spaces, take part in a discussion about urban design, and exchange thoughts on how to make our city even better. At the end of the competition period, the winning ideas were selected by a high caliber jury and announced at a block party at City Hall, where the chairs were gathered for a final spectacular display of Winnipeg innovation and pride. The winning idea – to hold a contest for kids to design environmentally themed art for city transit buses to encourage youth ridership – was implemented in the spring of 2016. Working together with Art City, an art competition called Imaginary Superbus was held at The Forks on May h.