/ Blog

January 22, 2020

The “Cool Factor” of Cold Storage: The Johnston Terminal

The Johnston Terminal was not built to be pretty, but functional.

In fact, a 1986 structural study of the Johnston Terminal described the building as “simple and utilitarian with no outstanding architectural features”.

Now, outstanding architectural features were not a requirement at the time of construction . When it was built in 1928, it was intended to be used as a cold storage warehouse for National Cartage and Storage Ltd – a subsidiary of the Canadian National Railroad. At the time, The Forks was a bustling site known as the CNR East Yards – brimming with train tracks and industrial crews. The Johnston Terminal was hidden away on the outskirts of the site and was far away from the public eye so an aesthetically stunning facade was likely the last thing on the company’s mind. They couldn’t have realized that one day their cold-storage warehouse would become one of the center-pieces of a massive tourist destination in Winnipeg.

Union Station at 123 Main Street with the Canadian National Railway East Yards behind it, seen here some time between 1911 and 1914, prior to the construction of the Johnston Terminal.

Source: The Rob McInnes Postcard Collection (Winnipeg Public Library)

Unknown employees of the CNR’s architectural department were responsible for the warehouse’s design, while Winnipeg contractors Carter-Halls-Aldinger carried out the plans. Simple and sturdy, the Johnston Terminal is supported by thick concrete foundation walls, concrete piers, and steel beams. On the upper floors of the warehouse, where the weight load would have been lighter, wooden posts and beams are used instead. Large recessed windows line the facade, separated by simple pilasters. The fourth storey windows are capped by brick corbelling.

Minor additions were made to the building in 1930, and for the next 30 years the National Cartage company and the CNR prospered at their site along the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. By the 1950s, though, rail yards were being relocated in Winnipeg and the rail industry as a whole was in decline. By 1977, the CNR East site was vacated and the industrial buildings on the property were left in varying states of disarray.

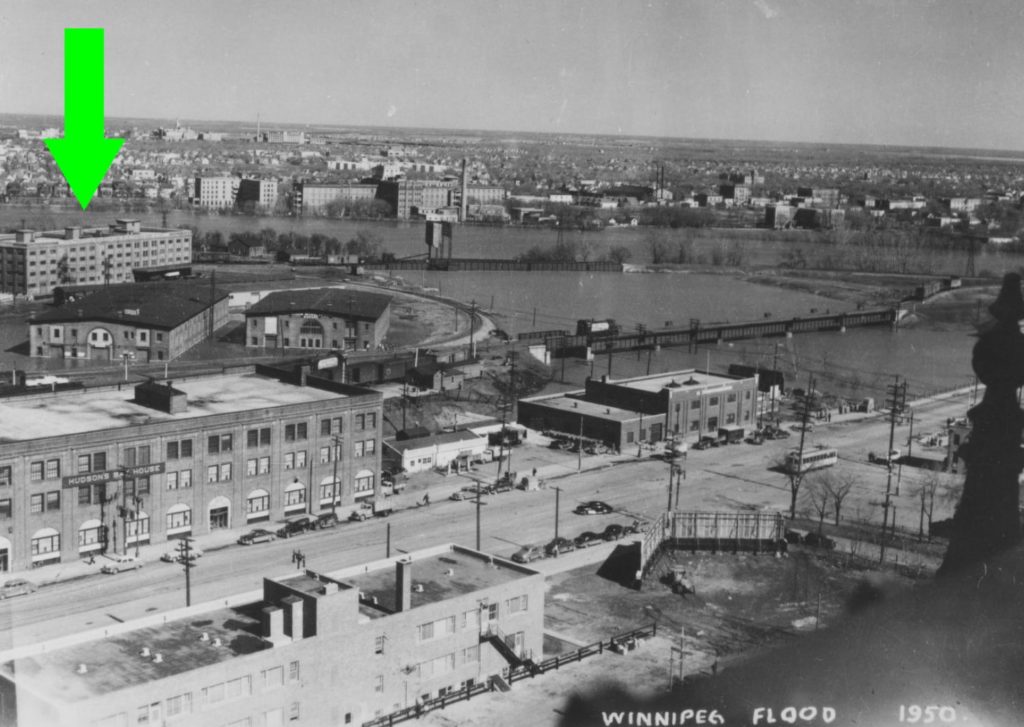

The south end of Main Street and CNR East Yards during the 1950 flood. The Johnston Terminal is highlighted with the green arrow.

Source: Martin Berman Postcard Collection (Winnipeg Public Library)

Enter, The Forks Renewal Corporation.

Founded in 1987 to revitalize the CNR East Site and funded by all three levels of government, the Forks Renewal Corporation’s plan was to reinvent the area as a “meeting place” with retail, recreation, and office spaces. A key component of these plans was the reuse of the heritage structures already on the lot. A study of the site had already been completed in 1986, and included reports on building conditions and recommendations for reuse. These would be incorporated into the 1987 plan for redevelopment.

According to the study, the Johnston Terminal was in good shape. The floors were worn due to years of carrying heavy loads and there was some evidence of water damage, but overall it was a prime candidate for redevelopment.

“The structure, foundations and shell of the building appear to be in good condition and capable of re-use,” the report states, “The rest of the building would have to be new construction.” (East Yard Task Force Study, Gaboury Associate Architects. July 31st 1986.)

The back of the Johnston Terminal in June 2014.

Source: Milorad Dimic MD, Serbia (CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Recommendations in the report suggested turning the Johnston Terminal into mixed-used office and retail spaces. Those who visit today know this was the eventual outcome, but other ideas were initially pitched first.

As a result of the Forks Renewal Corporation’s recommendation, the Johnston Terminal was designated by the City of Winnipeg on November 21st, 1988. In 1990, developers came forward with a plan to transform the old warehouse into a hotel and German-Canadian heritage centre. These plans never reached fruition. Instead, Marwest Properties came forward in 1992 with a different idea that was more in-line with the 1986 study: two storeys of retail, and two storeys of office space.

Along with the City’s Historical Buildings Committee, Heritage Winnipeg raised concerns about aspects of the redevelopment process and recommended that the building be delisted to stop the unsympathetic renovations. This was regarded as a highly unusual move then, and is still considered such today, but it signifies how attitudes towards heritage conservation have changed over the decades.

In 1992 Heritage Winnipeg had been in operation for 13 years and heritage by-laws in Winnipeg were just as new. Debates raged about how much leeway developers should be allowed during renovations, and the Johnston Terminal was placed in the middle of a tug-of-war between heritage advocates and developers.

At the core of the debate were two questions: How much of a building can be renovated and modernized before the historic characteristics are lost? How long can a building remain vacant waiting for the perfect plan, knowing that empty buildings are the most at risk? There are no easy answers to these questions – but years of experience mean that heritage advocates in Winnipeg are better equipped to find solutions.

As we know today, flexibility is key. Heritage buildings need modifications to suit new purposes and Heritage Winnipeg is happy to help developers find solutions and compromises to the issues that invariably arrive with redevelopment and occupancy.

Ultimately, the Johnston Terminal was not delisted as a historic structure and many of the changes that Heritage Winnipeg had initially opposed went through. A modern glass elevator was added to the west facade, wooden window frames were replaced with aluminum, and a new tourist centre was added to the building. But most importantly the building remained, and the building was being used.

The front entrance of the Johnston Terminal in August 2018.

Source: Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA (CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

After opening in 1993, tenants began to clamour for space in the newly renovated building. That appeal remains today, as the Johnston Terminal is home to a wide variety of local shops (including the largest antiques mall in the province), restaurants, and highly desired office spaces. More recently, in 2019, tech giants Amazon Web Services and Thinkbox took over 13,000 square feet of the upper level offices. This move is part of a growing trend of tech companies seeking out heritage buildings in historic districts. A Globe and Mail article extolled the benefits of these buildings just prior to Amazon Web Service’s move into the Johnston Terminal, stating:

After gobbling up historic buildings in major centres like downtown Toronto, San Francisco and elsewhere, developers and planners are discovering the virtues of older buildings in lesser-known areas that still have that all-important “cool” factor. As the ideal bait for luring skilled millennial and Generation Z knowledge workers away from the bright lights of the GTA or Silicon Valley, companies are happy to pay less for leasing or purchasing such properties; for young workers, it’s the appeal of more affordable housing, shorter commutes but still gain access to exciting, well-paying employment.

Both Heritage Winnipeg and the Forks Renewal Corporation (now The Forks North Portage) were acutely aware of the draw of historic buildings even back in 1987. The exact level of preservation may have caused disagreements, but no party wanted to see the Johnston Terminal demolished or left vacant. Thanks to the tireless efforts of sympathetic developers, advocates, and to a comprehensive development plan, no one had too.

Today, the Forks sees an average of 4 million visitors annually, and the Johnston Terminal at 25 Forks Market Road is there to help welcome them.

The front entrance of the Johnston Terminal in September 2017.

Source: Jessica Losorata (CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

East Yard Task Force Study | Gaboury Associate Architects - July 31, 1986

The Johnston Terminal: 25 Forks Market Road - Winnipeg, MB | Artis Reit

Johnston Terminal Redevelopment | Ralph W. Schilling Architects - 1992

Phase One: Concept and Financial Plan | The Forks Renewal Corporation - November 12, 1987

Stories of Success: The Johnston Terminal | Artis Reit