/ Blog

October 2, 2019

Missing Heritage On Main: The McIntyre Block

The 1960s and 70s were not banner decades for heritage preservation in Winnipeg. Scores of historic buildings were torn down in the interest of civic redevelopment – replaced by modernist office towers and, more often than not, drab surface parking lots. Occasionally, some concessions were made (such as the creation of Old Market Square to replace the former Fire Hall Number 1 on Albert Street).

In 1978, though, this all changed when plans were made to demolish the former Canadian Bank of Commerce, now the Millennium Center. A grassroots group of protestors gathered, and the building was spared. Following this, Heritage Winnipeg was founded by the National Trust for Canada (then Heritage Canada), the City of Winnipeg, and the Province of Manitoba in 1978. It was also around this time that the city of Winnipeg began to establish stronger heritage bylaws and designations – and it was at this point that the future of the McIntyre Block became startlingly uncertain.

When the McIntyre Block had opened in the winter of 1898, it was considered the finest office building in Winnipeg. It was, however, not the first McIntyre Block to exist in Winnipeg – the original opened in 1884, and was built local businessman Alexander McIntyre. The 1884 McIntyre Block was a red-brick building that quickly attracted high-end clientele, including lawyers, realtors, and financial agents, to the upper floor offices. Passing by the building on Main Street, though, pedestrians could pop in and visit some of Winnipeg’s more fashionable shops, including George Velie’s liquor store and John Erzinger’s barber shop. A series of expansions in 1886 and 1890 meant the building continued to grow, and would eventually boast eight retail stores, fifty offices, three halls and a collections room and offices for the University of Manitoba. The growth also bolstered Alexander McIntyre’s reputation as a shrewd businessman.

When he passed away after a prolonged battle with an unspecified illness in 1892 the Manitoba Free Press remarked that he left “the fine McIntyre Block on Main Street as a monument to his enterprise” (Manitoba Free Press, 1892-06-07 (8)).

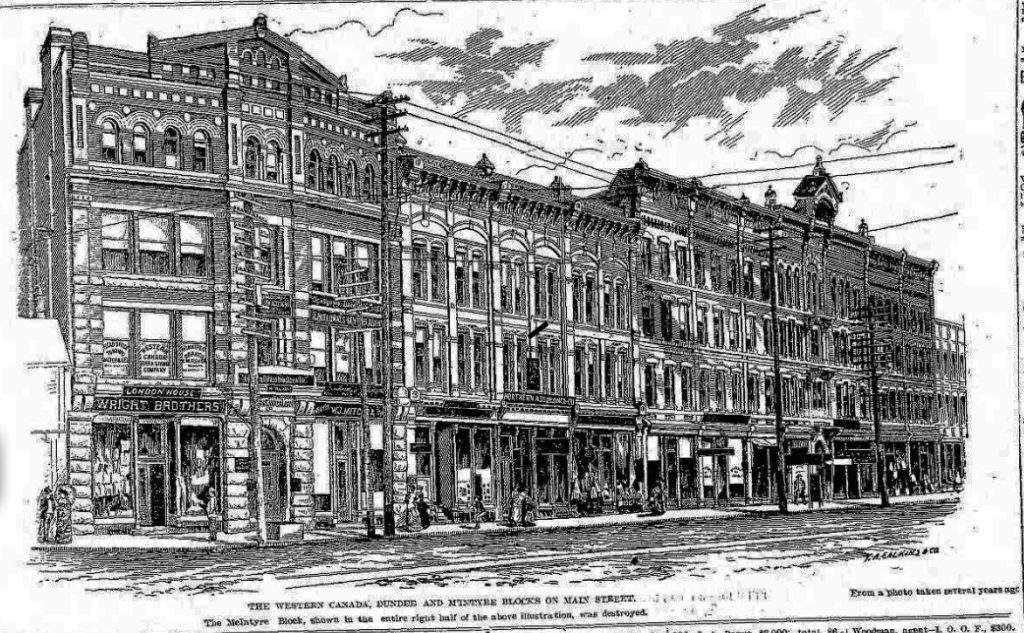

The original McIntyre Block takes up the majority of the right half of this illustration.

Source: Manitoba Free Press 1898-02-03 (3)

This monument would not last for long. In the early morning of February 2nd, 1892, a fire completely destroyed the building. Gone were the stores, offices, and collections – leaving behind only a dangerous and burnt wreckage. Estimates put the cost of damages near half a million dollars, and it was labeled one of the worst fires in Winnipeg’s history.

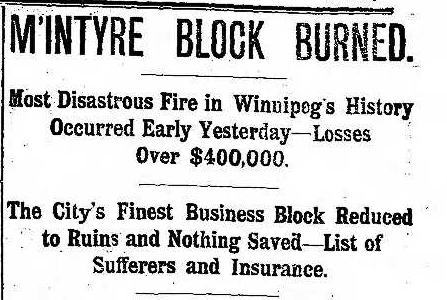

The 1898 fire was front page news for the Manitoba Free Press.

Source: Manitoba Free Press, 1898-02-03 (1)

Plans to rebuild were made almost immediately, and the McIntyre estate was hoping to building a new monument to the prominent Winnipegger. There was, however, a catch. A clause in Alexander McIntyre’s will forbade the construction of a new building on the site and insisted that the building could be “repaired of some calamity befell it” (CIHB, 224).

Architects Barber & Barber won the contract for the new McIntyre Block and used contractor Phil Burnett to construct the building. With an estimated cost of $125,000 – the new structure was five storeys high and 174 ft long along Main Street. Eight retail spaces were available on the main floor, while the upper levels consisted of uniformly sized office spaces. Local papers intently followed the construction process, and reported “the building will be thoroughly modern from the largest to the smallest point of detail” (Manitoba Free Press, 1898-04-01)

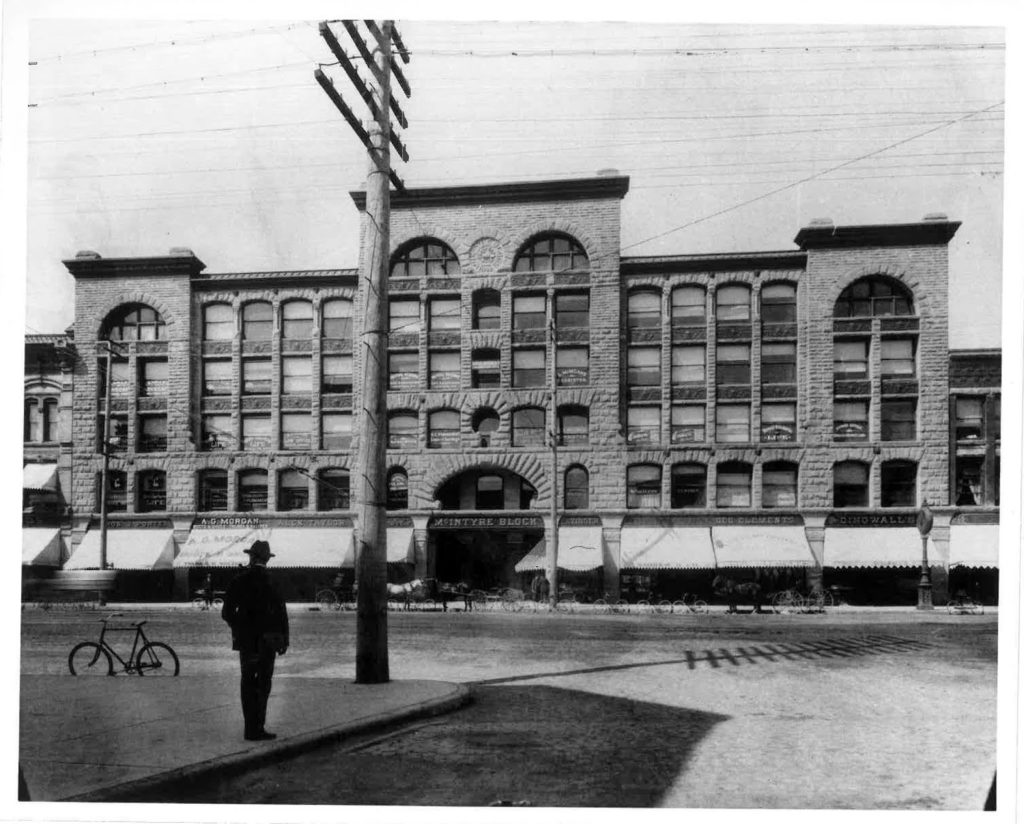

The McIntyre Block, prior to expansion, in 1905.

Source: Province of Manitoba Archives

Atop the building when it opened was a date stone, adorned with a beaver and inscribed with “McIntyre Block – 1898”. New tenants moved in around Christmas of 1898. George Andrews, a Winnipeg jeweller, was one of the first. Later, John Erzinger (who had operated out of the previous McIntyre block) moved in too.

Over the course of that first decade, the building was steadily maintained and expanded – and attracted some of the best tenants in Winnipeg. This was the office building for the elite lawyers, architects, and contractors of Winnipeg. It would remain this way into the 1920s, and then things began to change.

Advertisements for rental space within the McIntyre Block went up in Winnipeg papers, such as the Winnipeg Morning Telegram.

Source: Winnipeg Telegram, 1902-06-07 (25)

The Great Depression was not kind to the McIntyre block, and following the economic bust of 1929 the building never fully recovered. Randy Rostecki, writing for the Canadian Inventory of Historic Buildings, commented that “clearly, the McIntyre Block is a structure for which the Great Depression never ended.” (CIHB, 229.)

By 1977, the building was largely vacant – the top four floors had been closed, two elevators had been shut down and the offices were no longer filled with Winnipeg’s wealthiest businessmen, but instead a scattered assortment of eccentric tenants. Among them, a psychic, a bargain hunting agency, and a small religious group. A short National Film Documentary, made by Bob Lower, chronicles and interviews the tenants and footage shows a largely vacant and run-down interior – as well as a building owner with little attachment to the space itself.

The McIntyre Block from Robert Lower and Elise Swerhone on Vimeo.

Concerns were raised about the structural stability of the McIntyre Block, as well as the costs associated with repairing it. Thus, when the City of Winnipeg began designating historic structures in downtown Winnipeg in the late 1970s, and the McIntyre Block was considered a good prospect for designation, the building owners, Silpit Industries, balked at the prospect.

Given its prominent location on Main Street and its impact on the business history of downtown Winnipeg, the McIntyre Block seemed like a shoe-in candidate for protection, and with that the race was on for Silpit Industries to receive a demolition permit before the designation could go through.

Silpit Industries claimed that the demolition permit was simply a precaution – in case they wanted to demolish the structure sometime within the next five years. (tribune, June 7 1978). Silpit was also decidedly opposed to the incoming bylaws for the Historic Restoration Area. The complaint at the forefront: that these new city bylaws would interfere with the rights of private property owners. In response, Tribune columnist Susan Ruttan said it best:

“The bylaws do not eliminate the rights of the owners of historic buildings to be protected. What they do is provide a mechanism to balance those individual rights with the rights of the community.” (Winnipeg Tribune, 1978-08-12 (13)

The fight to save the McIntyre Block was contentious, with wealthy and influential developers pitted against the budding heritage conservation movement in Winnipeg. Over the course of 1978, multiple opinion pieces would appear in the Winnipeg Tribune on the subject of not just the McIntyre Block, but the future of our historic buildings.

In the eyes of some developers, Winnipeg’s dilapidated Main Street would scare off new business, with one developer claiming that “When potential investors come to the city and they look and they see a bunch of old-type buildings, and they look like the devil.” (Tribune, 1978-06-09 (14))

For conservationists, the McIntyre Block was an important part of the Winnipeg streetscape and should be preserved. Winnipeg’s stock of historic structures was remarkable, after all.

In the end, the building’s owners won out and a demolition permit was granted. There would be no five-year delay – the McIntyre Block had been dubbed a “rabbit’s warren” by engineers involved, and it would be torn down later in 1978. It was replaced by a surface parking lot, which is still there today.

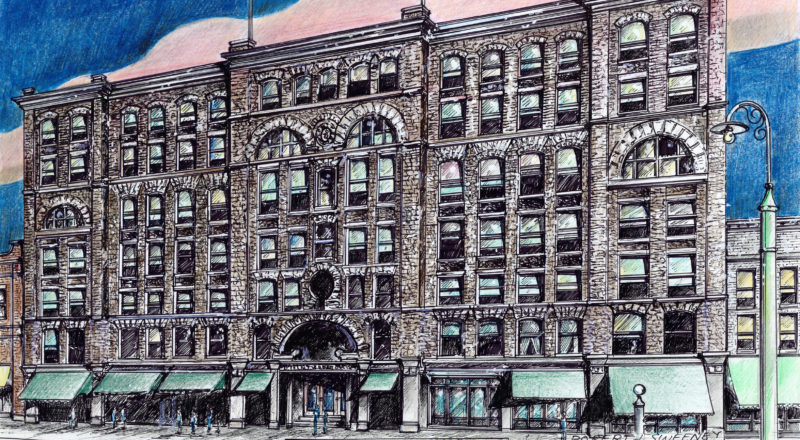

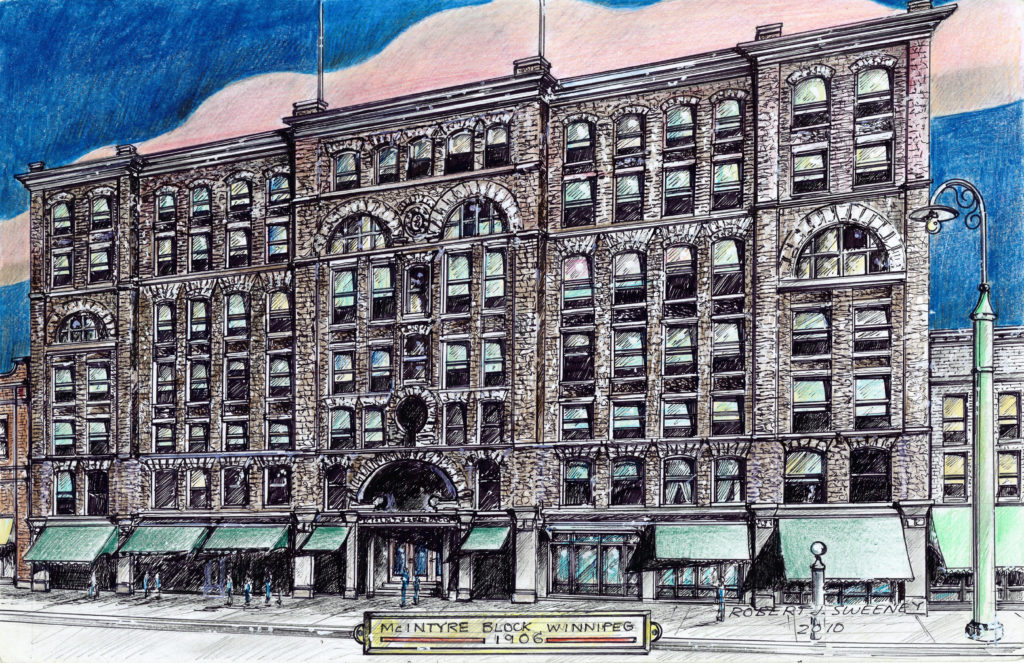

The McIntyre Block by Robert Sweeney. Print is available for purchase in the Heritage Winnipeg Store.

During the demolition, parts of the McIntyre Block were salvaged. In 2016, Shelmerdine Garden Center held a sale with 56 building fragments, including these pieces from the McIntyre Block and the Royal Alexandria hotel, with the proceeds going to support Heritage Winnipeg. Some of these fragments still remain with Heritage Winnipeg, awaiting a new home and a new use.

The first heritage conservation bylaws would go through and in 1979 11 buildings were put onto the Historical Resources List. In the 1980s 123 more would be added.

Heritage Preservation is so often depicted as an unending battle between developers and heritage professionals. We know today that the pair can work together, and in Winnipeg you can find many examples of rehabilitated historic buildings that allow for new economic growth. Red River College’s Princess and Paterson campuses repurposed a significant amount of the original structures, but are now part of a thriving learning institution. The Porter House Apartments, Forth, and the James Street Pumping Station also serve as excellent model for adaptive reuse within Winnipeg’s urban core. And, if you’re interested in purchasing any remaining pieces of the former McIntyre Block, or any other building shards, contact us at info@heritagewinnipeg.com.

SOURCES:

The McIntyre Block

Historic Sites of Manitoba: The McIntyre Block

Randy Rostecki, Canadian Inventory of Historic Buildings (1976).

Dictionary of Canadian Biography: McINTYRE, Alexander

Winnipeg Free Press

Winnipeg Tribune

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.