/ Blog

September 10, 2019

Main Street’s Bankers’ Row – An Historically Significant Streetscape

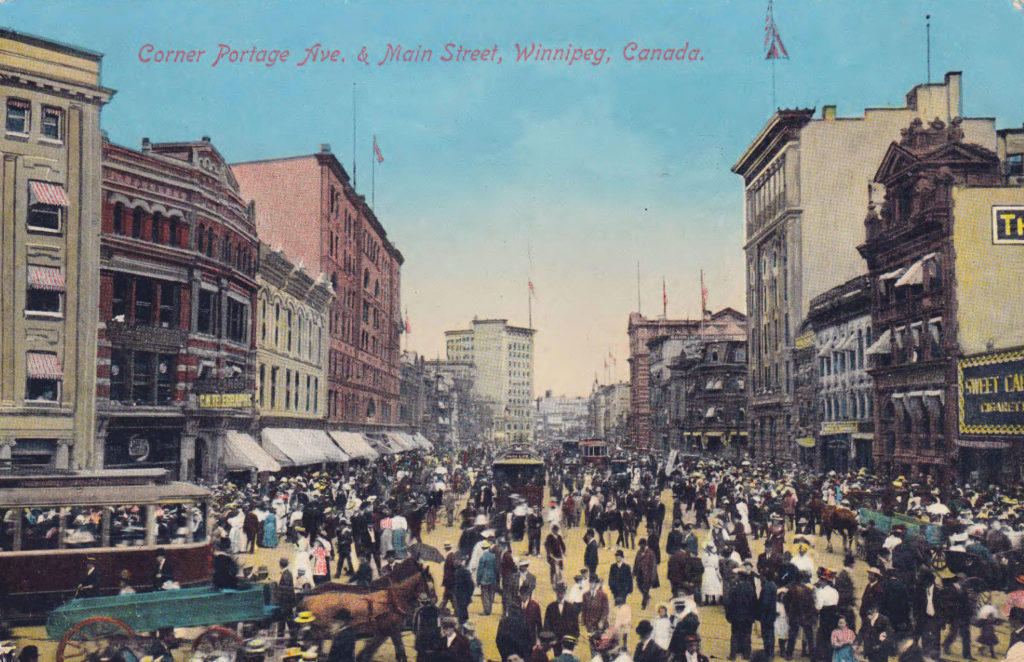

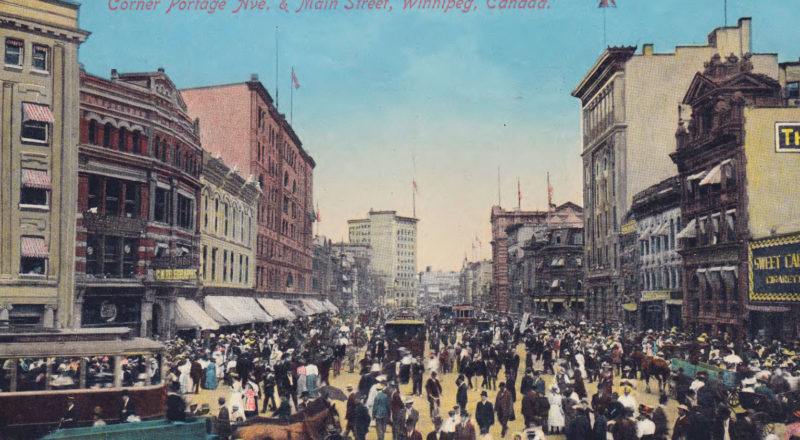

At the close of the First World War an informed pedestrian walking south on Main Street from the gingerbread style city hall to Portage and Main would have marvelled at Winnipeg’s magnificent bank architecture representing most of Canada’s major financial institutions. Along the west side of Main Street our pedestrian would have passed the Union Bank high rise with one of the tallest flag poles in the British Empire, the small but attractive Trader’s Bank, the palazzo style Royal Bank, its elaborate marble colonnaded Bank of Toronto neighbour, the highly eclectic Dominion Bank and the neo-Palladian Bank of British North America. Across Main Street the buildings became even more elaborate. There our pedestrian would have admired the Imperial Bank executed in what was considered to be the Bank of England style and the recently completed Bank of Hamilton with a two storey monumental banking hall base. Nearing Portage Avenue the monumental and neo-classical Canadian Bank of Commerce, the mid-size former Eastern Townships Bank, and the decorative Merchants Bank, Winnipeg’s first skyscraper vied for passerby attention. Finally at the corner of Portage and Main the streetscape reached a crescendo. On the south-east corner the starkly simple, neo-classical McKim, Mead & White designed Bank of Montreal dominated Winnipeg’s great crossroads. While the Trader’s, Dominion, Eastern Townships and Merchants Banks no longer grace Winnipeg’s streetscape the remaining buildings represent Canada’s most intact early twentieth century Bankers’ Row.

Looking north down Main Street’s Bankers’ Row from Portage Avenue circa 1909.

Source: PastForward.

Pre 1900 bank development was centred on Main Street’s east side. There in mainly rental offices Canada’s multiplicity of chartered banks transacted business. By the late 1890s the city’s banking premises proved inadequate. As Winnipeg emerged into a major railway, manufacturing, grain trade and wholesale distribution centre financial institutions proved eager to finance these activities and required more elaborate premises to attract customers.

At the turn of the century a plethora of chartered banks operated in Canada. Except for the Bank of Montreal which was national in scope and had financed the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway and was above all banker to the Dominion Government, Canada’s financial institutions were small regional businesses. However they had all survived the 1893 financial panic in the United States unscathed. Consequently they began viewing themselves as guardians of Canada’s finances. Confining their newspaper advertising to listing their assets and branch locations, they looked to distinctive architecture to attract business clients and small depositors. To these financial institutions, many with limited assets, a distinct corporate architecture could spell the difference between profit or failure.

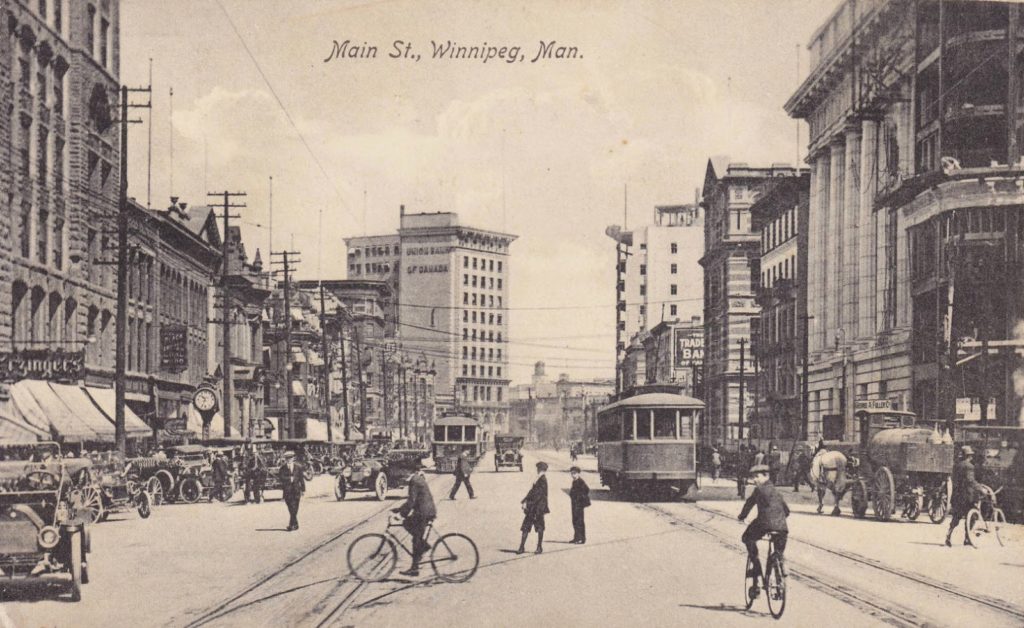

Looking north down Main Street’s Bankers’ Row from Portage Avenue in 1912.

Source: PastForward.

The 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago re-introduced North Americans to the ordered architecture of neo-classicism. The style suited bankers perfectly as it conveyed a sense of strength, purpose, stability and permanence – all useful attributes that bankers sought in their marketing. Neo-classicism also appealed to architects. In an industrializing and expanding North America the orders of neo-classicism proved suitable for teaching in new faculties of architecture being set up across universities in the United States and Canada. Leading North American architects including McKim, Mead & White of New York City, Darling & Pearson of Toronto and Andrew T. Taylor of Montreal secured commissions to design neo-classical banks in Winnipeg.

The first buildings on Bankers’ Row featuring neo-classical motifs were erected from 1898 to 1902. These buildings blended neo-classical elements with the older highly adorned Victorian styles. The Dominion Bank at the south-west corner of McDermot and Main, the Merchant’s Bank and Darling & Pearson’s first Canadian Bank of Commerce constitute examples of this style. All have subsequently been demolished.

On Banker’s Row the majority of early twentieth century banks remain standing and retain their pre-1918 appearance. In chronological order of construction below are brief historical sketches of these edifices.

The Bank of British North America constituted one of Canada’s oldest financial institutions. It operated in Canada under a British charter with headquarters in Montreal. In 1903 the company erected a branch bank at 436 Main Street. Designed by Andrew T. Taylor of Montreal to emulate its 1847 neo-Palladian style Montreal headquarters, the building was constructed by leading Chicago contractor William Grace Company. In 1914 the building received a large rear extension. In 1918 the Bank of Montreal purchased the Bank of British North America. A year later the Bank of Montreal subsidiary Royal Trust took over the building and operated it as a banking hall for 45 years. Today the building functions as a night club. The building represents the only example of the Bank of British North America corporate style in Winnipeg.

The Bank of British North America in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The Union Bank was incorporated in 1865 and remained Quebec City based for over four decades. In 1882 it opened a branch in Winnipeg. In 1903 it began construction of a skyscraper across William Avenue from city hall. The building was designed by leading Toronto architects Darling & Pearson and encompassed a two storey high banking hall base with rental storeys above. The banking room conveyed an image of wealth and stability with a marble floor, marble Ionic columns and a costly gold leaf ceiling. In 1912 the Union Bank relocated its headquarters from Quebec City to this iconic Winnipeg edifice. Facing financial difficulties in 1925, the Union Bank sold its assets to the Royal Bank. Until 1974 the Royal Bank retained a presence in the building. Recently Red River College has restored and expanded the building. It is now known as the Paterson Global Foods Campus. The Union Bank at 504 Main Street is the oldest surviving skyscraper in the city.

The Bank of Toronto was established in 1855. A latecomer to the Winnipeg financial scene, in 1905 it opened a temporary office in rental quarters. Purchasing a lot from a speculator in the same year for $66,000, it commissioned Montreal architect Howard C. Stone to design an edifice which would draw clients from the nearby Dominion Bank, the first Canadian Bank of Commerce and the Bank of British North America. Opening for business in May, 1907 the building constituted an exercise in architectural conservatism. Stylistically similar to countless other banks in Canada’s major cities, the solid white marble colonnade, frieze and balustrade from Blue Ridge Quarries in Georgia distinguished it from its competitors. Until 1952 the Bank of Toronto fulfilled its original function. Today its solid marble facade is unique in Winnipeg.

The Bank of Toronto on the far left with the Royal Bank just to its right, in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The Imperial Bank commenced business operations in Toronto in 1875. Under the authoritarian management of Douglas R. Wilkie from 1876 to 1914, the Imperial Bank pursued “an extreme cautiousness” and “a mania for holding large cash reserves.” Arriving in Winnipeg in December, 1880 it rented quarters at Bannatyne and Main before purchasing the strategic Bankers’ Row site in 1898. In 1906 the old building was demolished and architects Darling and Pearson designed a $160,000 four storey steel frame neo-classical building with walls two feet thick. The recessed entrance was flanked by two fluted Ionic columns on the Main Street elevation and a pilastered side elevation on Bannatyne Avenue. The overall design served as a model for future Imperial Bank buildings in Calgary, Alberta and Windsor, Ontario. In 1961 the Imperial Bank amalgamated with the Canadian Bank of Commerce. As late as 1982 441 Main Street continued to fulfill a banking function. Today it is used as a night club. The building is one of the best preserved examples of early twentieth century Imperial Bank architecture.

The Imperial Bank of Canada in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The Royal Bank was originally incorporated as the Merchant’s Bank of Halifax in 1869. In 1894 the company relocated its headquarters to Montreal. Planning a nation wide expansion, in 1900 it changed its name to the Royal Bank of Canada. The Royal Bank constituted the last major financial institution to open in Winnipeg. After a brief stay in rental quarters in 1906 the Royal Bank purchased the Imperial Dry Goods Building for the princely sum of $200,000. Two years later it contracted North America’s leading neo-Renaissance architects Carrere and Hastings of New York City to design a suitable edifice. The building site presented major challenges to the architects. Next door stood the marble-fronted Bank of Toronto. Nearby the recently completed Imperial Bank and Bank of British North America attracted clients with imposing facades and opulent banking halls. Carrere and Hastings responded by designing a temple bank like no other in Winnipeg. Utilizing the side walls of the former dry goods store, the building presented a palazzo elevation devoid of columns and pilasters topped by a Spanish style tiled roof. In the interior the usual marble floor, marble walls and marble counters prevailed. The 460 Main Street structure fulfilled a banking function for only sixteen years. In 1926 the Royal Bank re-located its main Winnipeg office to the former Union Bank headquarters across from city hall. The building comprises the only neo-Renaissance bank on Banker’s Row and one of the few monumental bank buildings designed by Carrere and Hastings extant in Canada.

The Canadian Bank of Commerce at 389 Main Street is the second temple bank to occupy its site. Following the dismantling of Darling and Pearson’s 1898 structure and subsequent re-erection in Regina, these leading bank architects turned their attention to designing one of Winnipeg’s largest and most elaborate bank edifices. Modelled after the Bank of Commerce regional headquarters in Montreal, it cost $750,000 to construct. The exterior displayed a facade of Stanstead granite quarried from Quebec’s Eastern Townships. The banking hall attracted corporate clients with marble floors and walls. The Winnipeg Tribune proclaimed that “all that art and money could do to produce a perfect building has been done.” The Canadian Banker praised the building as “one of the most satisfactory of its type …and eminently suited to the requirements of a large financial centre.” From the date of its completion to 1969 the structure serviced the bank’s needs well. After standing vacant for three decades the Canadian Bank of Commerce was re-borne as the Millenium Centre. The building stands as one of Canada’s iconic temple banks and one of the three best examples in Canada of the Bank of Commerce style of architecture.

The Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The Bank of Montreal at Portage and Main is the most grandiose building erected by that company outside Montreal before 1930 and a prime example of its corporate style. Prior to its completion in 1913 the bank enjoyed a long and profitable history in Winnipeg. In 1881 it constructed a red brick structure across Main Street from the current building. With competition from the monumental buildings of other financial institutions, by 1909 that building was obsolete. The Bank of Montreal purchased the large Canada Permanent corner site and commissioned the renown New York City architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to design its most monumental regional office in Canada. Costing a total of $1,295,000, the building is the only large free standing bank in Canada designed by that architectural firm (their building in Montreal being an annex to the existing headquarters). Similar to the Roman temple style Montreal headquarters, the building flaunted an exterior flanked by six unfluted Corinthian columns weighing twelve tons each. The interior was an exercise in the conspicuous display of wealth. The banking hall featured columns and side walls of light buff Botticino marble imported from Northern Italy and a marble floor extending the duration of the room. A gold leaf ceiling, one of three in Winnipeg completed the arrangement. Since its opening the building has fulfilled a banking function. In 1975 to 1976 the edifice underwent a $2.4 million restoration though its banking function is being shifted to 201 Portage Avenue in 2020. Today the building dominates Winnipeg’s main intersection much as it did almost 110 years earlier.

The Bank of Montreal in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The Bank of Hamilton was incorporated in 1872. According to historian R.R. Rostecki it opened its first branch outside Ontario in Winnipeg in 1896. In 1897 the bank purchased a lot on Main and McDermot which included a four storey mansard roof structure. The building was upgraded and expanded but eventually experienced structural problems caused by the construction of the second Canadian Bank of Commerce on the adjoining property. In 1915 that severely damaged building was demolished. One of Winnipeg’s most prominent architects, John D. Atchison who had earlier designed the Boyd Building and Union Trust Building was hired to pen plans for a new skyscraper similar to corporate headquarters in Hamilton. Started in 1916 at a cost of $400,000 and completed two years later, the building was the most lavish branch in Canada constructed by the Hamilton company. An unadorned two storey high stone base with Renaissance entrance and eight upper rental floors greeted customers. The banking hall possessed the usual accoutrements expected by clients including a marble floor, walls and countertops with bronze grilles all topped by a ceiling of antique gold. But building use as an independent bank was short lived. In 1924 the Canadian Bank of Commerce acquired the Bank of Hamilton. Until completion of the Richardson Building in 1969 it functioned as an office annex to the Bank of Commerce regional headquarters next door. Later it provided quarters for the United Grain Growers. Today City of Winnipeg offices are located in the building. The Bank of Hamilton is historically significant as the last monumental bank to be erected on Bankers’ Row. It is perhaps the finest of architect John D. Atchison’s creations.

The Bank of Hamilton is on the left with the Canadian Bank of Commerce on the right, in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The 1918 armistice ending World War I inaugurated years of economic uncertainty in Canada. After a brief period of prosperity a severe recession followed. The economic roller coaster led to multiple bank takeovers. By 1925 the Quebec Bank, Northern Crown Bank, Bank of British North America, Bank of Ottawa, Bank of Hamilton, Molson’s Bank and Union Bank had all been purchased by larger more economically viable competitors (while the Trader’s and Eastern Townships Banks had been absorbed by other financial institutions before the war). The Merchant’s Bank and Home Bank collapsed, the former being acquired by the Bank of Montreal and the latter ceasing operations. The takeovers and bankruptcies rattled public confidence in Canada’s banking system. Monumental banks no longer created the illusion of being safe places to invest one’s capital. Canada’s surviving financial institutions turned to newspaper advertising to attract customers. By 1930 they had largely abandoned the temple bank concept. On Main Street’s Bankers’ Row Canada’s chartered banks bequeathed a legacy of the best preserved early twentieth century banking district in Canada.

The author wishes to thank Randy R. Rostecki for his helpful comments and suggestions for this article.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Guest blog written by David Spector, author of Assiniboine Park: Designing and Developing a People's Playground.

Edited by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

City of Winnipeg Buildings Report - 395 Main Street- Bank of Hamilton Building, 24 September 1982- Appendix 1 - R.R. Rostecki, Hamilton Building, 395 Main Street.

David Spector, "McKim, Mead & White and the Neo-Classical Bank Tradition in Winnipeg," Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada Bulletin, Volume 7, Number 4, December 1981, pp. 2-4.

David Spector, Monuments to Finance - Volume 1 - Three Winnipeg Banks, Winnipeg: Report of the City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings Committee, December, 1980.

David Spector, Monuments to Finance - Volume 2- Early Bank Architecture in Winnipeg, Winnipeg: Report of the City of Winnipeg Historical Buildings Committee, August, 1982.

David Spector, "The Buildings of the Winnipeg Based Union and Northern Crown Banks: A Glimpse into Early Twentieth Century Corporate Architecture," Manitoba History, No. 21, Spring, 1991, pp. 25 - 31.

David Spector, Temples of Finance: Canada's Chartered Banks and Their Monumental Buildings, Unpublished Manuscript, 2019.

Great article Thanks for sharing