/ Blog

March 26, 2020

Hospital Histories: The Winnipeg Municipal Hospital

Two archways are hidden on the grounds of the Riverview Health Centre at 1 Morley Avenue. Carved into the archway’s pediments are a stylized cross and the words “NURSES ENTRANCE”, giving two small hints into what the doorways were once attached too. Plaques sit nearby for curious passerby’s to read about the history of these architectural fragments, and to learn of what came before the Riverview Health Centre.

Since 1912, the property at 1 Morley Avenue has had a hospital. At the time it was a city owned facility with just one building. Over the course of the 20th century, this would grow from one hospital building to three: the King Edward Hospital (1912), the King George Isolation Hospital (1914), and the Princess Elizabeth Hospital (1950). Together these three buildings were known as the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital.

|

| The former entrance to the nurses residence at the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital. Source: City of Winnipeg. |

|

| The former entrance to the King George Isolation Hospital, sitting on the grounds of the Riverview Health Centre. Source: City of Winnipeg. |

The first of the buildings to open, the King Edward Memorial Hospital, was designed by architect George Teeter. The King Edward Hospital had a centralized entrance with contrasting sections of red and grey brick. Branching off from the entrance section, the bulk of the structure seems to have been made of grey brick with slight red brick accents. The building sat on a raised foundation, likely a sound design choice given the properties proximity to the Red River.

Both the King Edward Memorial Hospital and it’s neighbour, the King George Isolation Hospital, were built to handle cases of communicable diseases in Winnipeg. In 1910, these diseases ran the gamut from smallpox, diphtheria, typhoid, polio, and tuberculous. Due to poorer sanitation, costly healthcare, and less accessible healthcare these diseases could (and did) spread quickly in Winnipeg. Prior in 1912, Winnipeg dealt with outbreaks by renting out or buying additional buildings to act as isolation hospitals and this not always a practical or financially viable option. It is understandable, then, that many were keen to have a more permanent facility built.

|

| The King Edward Hospital near the King George Isolation Hospital. Source: Winnipeg Library, Martin Berman Postcard Collection. |

|

| The King George Isolation Hospital Source: Archives of Manitoba |

The Winnipeg Municipal Hospital was the very picture of modernity, and a great deal of attention was paid both to the building’s construction and to it’s opening ceremony. Even 26 years after the building’s opening, the Winnipeg Tribune recalled the spectacle of the opening ceremony of the King Edward Hospital, and the placing of the cornerstone for the King George Isolation Hospital. Large crowds of physicians and politicians had gathered, mayor and council among them, to watch the Duke of Connaught and his daughter Princess Patricia open the hospital and lay down the cornerstone. The surrounding area was largely “bald, bare prairie” according the Tribune, but this would change quickly. The King George Isolation Hospital was completed two years later, and designed by architect Herbert Bell Rugh. It’s entrance sat on an angle, with a decorative arched entrance way and carved stone detailing along the parapet. Unadorned brick pilasters separated the rows of windows along the facade. By 1920 a Nurses’s Residence was added to the site. This, too, was a practical choice – these nurses were working daily with highly contagious diseases, and they could unknowingly and unwilling carry those same diseases back to their homes. As nurses were generally unmarried women, this likely would have meant going home to aging parents or to a renting room in a shared boarding house.

|

| The Duke of Connaught officially opening the King Edward Hospital. His daughter, Princess Patricia, stands to the side holding a parasol. Source: Winnipeg Library, Rob McInnes Postcard Collection. |

The on-site facilities at the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital proved invaluable in slowing the spread of influenza in Winnipeg during the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic. The disease outbreak, also known as the Spanish Flu, began on the war front during World War One and spread across the world as soldiers returned home. It’s estimated 500 million people globally were infected during the outbreak. The epidemic hit Winnipeg in early October and the city found itself quickly overwhelmed. To slow the disease spread in Winnipeg, the city shut down all public gathered places and events were cancelled. Isolation hospitals like King George were a vital service, and kept infected patients separate from patients with other conditions. In fact, the King George Hospital accepted the first influenza patient who was too sick to be treated at home on October 11th, 1918. At the end of the epidemic, influenza had killed at least 1,200 Winnipeggers (the city had a population of 180,000 at the time). Globally, 500 million people were infected and an estimated 50 million died (some put the death toll much higher, at 100 million).

|

| The Nurses Home, built in 1920, on the grounds of the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital. Source: Archives of Manitoba. |

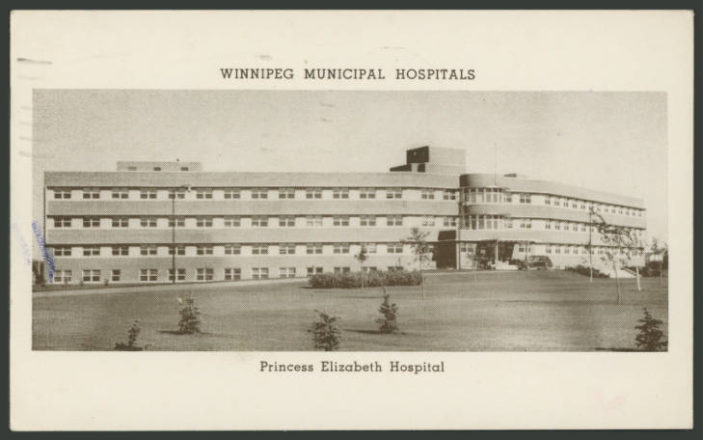

Slowly but surely the city recovered, the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital carried on. A new addition was constructed in 1950, this time to provide long-term recovery care. The Princess Elizabeth Hospital was constructed between 1948-1950, and designed by the architecture firm of Moody & Moore & Partners. Modern in it’s design, the building has rows of windows that highlight the horizontal. A curved wall of windows swing out above the building’s entrance. Inside the well-lit facility were an additional 200 patient beds. Now known as the Princess Elizabeth Building, it is the only part of the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital that still stands today.

|

| The Princess Elizabeth Hospital was a modern addition to the hospital complex upon it’s opening in 1950. Source: Winnipeg Public Library, Martin Berman Postcard Collection. |

The Winnipeg Municipal Hospital was put to the test again in the 1950s, when the city was faced with a large polio outbreak. Polio today is much less of a threat thanks to the creation of the polio vaccine in the 1950s, but in the early 20th century it was a much more serious risk. Also known as poliomyelitis, polio is a viral illness that is known to attack the brain and spinal cord. In milder cases polio only results in flu-like symptoms, but the virus can also cause meningitis, muscle weakness, and paralysis. Polio outbreaks were not unusual, and Winnipeg had already faced several outbreaks by 1953. As such, the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital was well-equipped to deal with such outbreaks.

Inside the King George Isolation Hospital, rows of iron lungs, or respirators, could be found. Developed in the 1920s, the iron lung was used to assist patients affected by respiratory failure caused by a variety of illnesses – polio among them. For many a stay in an iron lung was temporary. Others were not so lucky. In 1936, a young Winnipeg woman named Inez Woollam contracted polio and, faced with respiratory paralysis, was placed in an iron lung – where she mostly remained until her death in 1951. Woollam was one of the first iron lung patients in Winnipeg and became known as “The Iron Lung Girl”. She was not alone in her long-term stay. In 1941, sixteen-year-old Lena Barker was similarly paralyzed and became Winnipeg’s second Iron Lung Girl. Barker and Woollam became roommates, and fast friends.

In the spring of 1950, during one of the worst floods of the 20th century, the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital and the Iron Lung Girls got some rare fresh air in the midst of their evacuation to higher ground at Deer Lodge. Once flood waters had receeded, the women returned back to their room at the King George Hospital. Woollam passed away in 1951, while Barker died in 1956.

Though Barker and Woollam were permanent residents, most polio patients only had temporary stays at the Municipal Hospital. 1953 saw one of the worst polio epidemics on record, for which Winnipeg gained international attention. This was, in part, due to the severity of the outbreak but also a result of the dedicated community fundraising to pay for equipment and cover medical costs. As patients recovered from this outbreak, polio victims moved throughout the facilities at the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital. They were initially treated at the King George Isolated Hospital, and would be transferred to the Princess Elizabeth Hospital for physiotherapy once recovered.

Hundreds of sick Manitobans passed through the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital for treatment in 1953, and during another polio outbreak in 1954. This changed in 1955, when Joseph Salk’s new polio vaccine was approved for Canadian use and polio numbers began to drop. As vaccines were developed, and access to healthcare increased, communicable disease numbers decreased significantly in Winnipeg and by the 1960s the King George Isolation Hospital was to treat chronic illnesses like multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, cancer and postpoliomyelitis.

In 1992 the ownership of the Winnipeg Municipal Hospital changed hands. No longer managed by the city, instead a community board of directors ran the facility. Its name was changed a year later, to the the Riverview Health Centre. It didn’t take long for other changes to come. Though the King Edward Hospital and King George Hospital had served a prominent role in Winnipeg health, both structures were outdated. A $59 million dollar plan came through to demolish both buildings and replace them with a modern facility. The newer Princess Elizabeth Hospital was included in the new complex, which included 388 beds and a interpretive centre that explores the history of the hospital.

The Riverview Health Center is still a community hospital and continues to serve it’s patients with dignity and grace while the two archways stand as a monument to how far Winnipeg healthcare has come!

SOURCES:

George Gaspar Teeter | Manitoba Historical Society

Herbert B. Rugh | Winnipeg Historical Society

The Great Polio Outbreak of 1953, Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 | Bruce Cherney, Winnipeg Real Estate News

Survival of the Weakest | Bill Redekop, Winnipeg Free Press 02/15/2019

The Great Pandemic | Bill Redekop Wave Magazine, NOV/DEC 2018

Riverview Health Centre History

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 1950-05-06 (Page 1)

The Winnipeg Tribune, 1976-05-06 (Page 49)

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 1938-05-11 (Page 10)

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 1951-03-12 (Page 3)

The Winnipeg Free Press, September 12, 2001 (100)

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.