/ Blog

October 30, 2019

History Among the Headstones: Elmwood Cemetery

The opening of Elmwood Cemetery in 1902 was more controversial than many of Winnipeg’s other cemeteries. It is a privately owned, non-denominational cemetery built on 37 acres of land in the municipality of Kildonan – and was the first cemetery of its kind in Winnipeg.

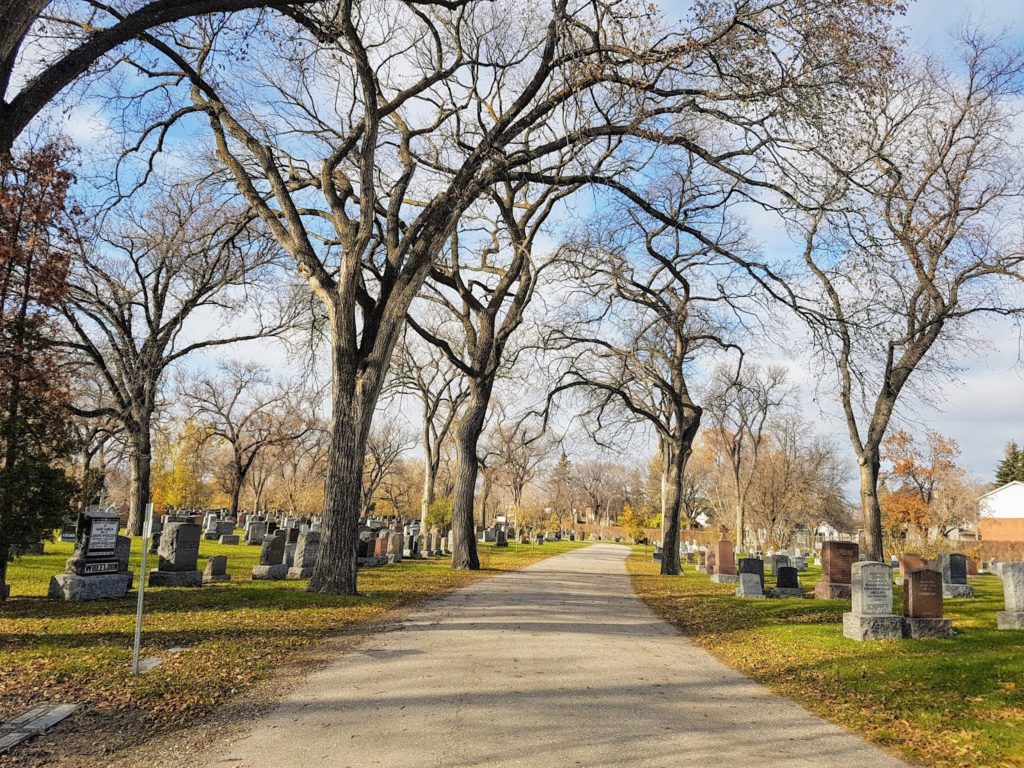

Plans for the cemetery were meant to maintain as many of the surrounding trees as possible. It was these old hardwood trees, including ash, maple, and elm that led to the cemeteries name of Elmwood. To add new greenery, such as shrubs and flowerbeds, a nursery with a greenhouse was added to the lot. In the early years of the cemetery, it was possible to purchase flowers and shrubs as well as a burial plot.

The gates to Elmwood Cemetery off of Henderson Highway.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

One of the mausoleum’s at Elmwood Cemetery. This one belongs to the Campbell and Bathgate families.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Frank Nutter, a landscape architect from Minneapolis, was responsible for designing the winding gravel pathways and park-like spaces of Elmwood Cemetery. The landscaping, and the quieter location away from the hustle and bustle of downtown Winnipeg, made Elmwood Cemetery an attractive spot for burials. The Morning Telegram claimed that Elmwood would be “The most desirable place of its kind in the country” (1902-06-28, 32).

A bench sits in the middle of Elmwood Cemetery, one of many park-like details that can be found around the area.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Issues arose, however, because the cemetery was being built in the Municipality of Kildonan and not in the City of Winnipeg proper. The municipality had not been consulted, and local property owners were worried about their property values decreasing if the cemetery were too open. There were protests and letters of concern sent to the Manitoba Legislature, but the Province of Manitoba ignored the complaints and authorized the cemeteries opening. Later, in 1906, when the Municipality of Kildonan was incorporated into the City of Winnipeg – the neighbourhood surrounding the cemetery adopted the Elmwood name.

Walking along these winding pathways, today, you can find the names of many prominent locals who are buried here. Among the recognizable names are two Free Press employees: Ella Cora Hind and John W. Dafoe.

One of the tree-lined pathways. The many trees found in Elmwood Cemetery helped name both the cemetery and the surrounding neighbourhood of Elmwood.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Though she was born and raised on an Ontario farm, Hind had a keen eye for journalism. In 1882, shortly after her arrival in Winnipeg, she applied for a job with the Winnipeg Free Press. They’d been in print for just ten years, and then-editor William Luxton turned Hind away with the curt explanation that the newspaper business was “no place for a woman”. Undeterred, Hind took up work as a typist in Winnipeg and kept pushing. By 1901, she’d earned a place as the agricultural correspondent for the Free Press – a job she’d hold for decades to come. At age 75, Hind traveled to 25 different wheat producing countries and chronicled her travels through letters in the Winnipeg Free Press. She’d become such a mainstay of the agricultural community that upon her death in 1942 the Grain Exchange stopped trading for two minutes in her honour.

Ella Cora Hind (1861-1942) seen here investigating a field for her role as agricultural reporter for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Source: Province of Manitoba Archives

John W. Dafoe, much like Hind, was a journalist through and through. Throughout the 1870s-90s, Dafoe worked a variety of editorial and reporting jobs at such places as the Manitoba Free Press (1886-1892), The Montreal Herald (1892-95) and the Montreal Star (1895-1901). In 1901, he would return to Manitoba and took the job of Editor in Chief of the Winnipeg Free Press. Under Dafoe, the Free Press could grow significantly and became a source of both Canadian and international news. Dafoe would remain in this position until his death in 1944.

Also buried within Elmwood Cemetery are two victims of Earl Nelson, who is considered to be one of North America’s earliest serial killers. Beginning in 1926 with the murder of landlady Clara Newman in San Francisco, Nelson’s year-long murder spree was widely followed by papers across North America. Before his identity was discovered, American papers gave Nelson a variety of nicknames, including “The Dark Strangler” and “Gorilla Hands”.

In June of 1927, Nelson began hitchhiking to Winnipeg from Chicago; he arrived in the city on June 8th, visiting a tailor to obtain a new suit (the one he’d arrived in he been stolen from one of his previous victims) and renting a room from landlady Mrs. Hill in Winnipeg’s North End.

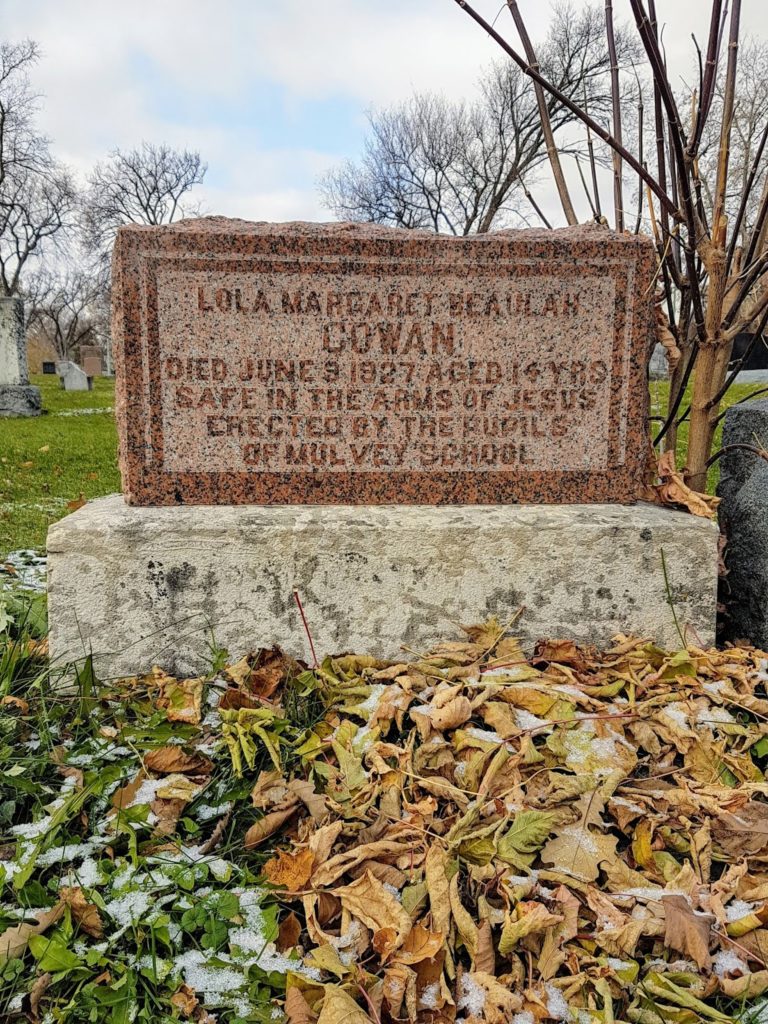

It was here that he would encounter 14-year-old Lola Cowan. For much of the evening on June 8th, Cowan had been out selling artificial flowers on Winnipeg’s streets. It’s believed that Nelson offered to buy one of Cowan’s flowers, if she would follow him to his room so he could grab the money required. After luring her to his room Nelson assaulted and murdered Cowan, hiding her body under the bed and fleeing with her belongings. Her body would not be discovered until the next week, on June 13th.

By the time both Cowan and Patterson’s bodies had been discovered, Nelson was hiding out in Headingly. Local and provincial police were working overtime to apprehend Nelson, covering border stops and watching major highways in the hopes Nelson may pass by in an attempt to escape back to the United States.

On June 16th, Nelson was finally captured by police in Killarney and locked up in the local jail; Nelson managed to escape using a rusty nail file. Within twelve hours, though, he had been recaptured. Unfortunately for the Nelson, the train he’d attempted to use to escape was also being used to transport Winnipeg Police Officers. He was quickly noticed by the officers on board and re-apprehended.

Lola Cowan, and Emily Patterson, are now buried next to each other in Elmwood Cemetery. Separate funeral services took place for the victims on June 15th, 1927, and scores of floral tributes arrived for both of their graves.

Classmates of Cowan from Mulvey School visited to make wreathes, and some of the stronger children in her school acted as pallbearers. They would also help pay to erect her tombstone.

Emily Patterson’s funeral was well-attended by members of the St. Andrews Church, where she was an active member of the Ladies Aid Group and where her husband sang in the choir. Around 130 members of the local Mother’s Club also attended.

The tombstone for Lola Cowan, erected by her classmates at Mulvey School.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

One of the Winnipeg Coroner’s photographers can also be found in the Elmwood Cemetery. Lewis B. Foote was one of Winnipeg’s most prolific photographers, and publishing books include many of his more popular photos. Foote is responsible for taking some of the more well-known photographs of the Winnipeg 1919 General Strike, including the infamous picture of a tipping streetcar.

Lewis Benjamin Foote.

Source: Province of Manitoba Archives

Another more tragic story in the cemetery is tied into four separate graves – that of firefighters Donald Melville, Arthur Smith, Robert Stewart and Robert S. Shearer. The Winnipeg Theatre was a nice enough theatre when it first opened in 1883, but by the 1920s it was largely considered a fire hazard. The building accommodated a 1,000-seat auditorium on the 2nd floor, above a main floor of retail shops. The brick-veneered wooden walls were hardly stable and when the wall facing Adelaide Street collapsed four fighters were trapped underneath the rubble and subsequently killed. Following the funerals, all four fire fighters were buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

Elmwood Cemetery in October 2019.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Further along the path is the Field of Honour, a nationally designated zone that commemorates the veterans buried in Elmwood Cemetery.

The Field of Honour in Elmwood Cemetery.

Source: Sabrina Janke for Heritage Winnipeg

Elmwood Cemetery was built for just 25,000 internments in 1902. Now, as of 2014, there are over 52,000 people buried in this historic graveyard. In wandering old cemeteries today, locals can visit the final resting places of significant Manitobans and new stories about our cities history.

SOURCES:

Elmwood Cemetery History

Bill Redekop, Headstones and History, Winnipeg Free Press

Winnipeg Police History

Manitoba Historical Society

Winnipeg Tribune

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.