/ Blog

October 22, 2020

Hard Times for Henderson House

Locked away behind a chain link fence at the back of St. Norbert Provincial Heritage Park sits Henderson House. Once a pristine example of Red River frame architecture and one of the oldest houses in Winnipeg, it has been left to rot, history turning to dust right before our eyes. Built by a family whose name is now found throughout North Kildonan, this house is home to both mystery and resilience. Saved from a brush with demolition because people could see its historic value, it was moved across the city until the time was right for it to return home. But out of sight and out of mind, Henderson House has been left to decay into obscurity. A victim of demolition by neglect, it is trapped in purgatory far from its community, crumbling more each day, wasting all opportunities to share its rich past and inspire a new generation.

Henderson House was already in a sad state in August 2010, a forgotten project locked away and left to deteriorate at St. Norbert Provincial Heritage Park.

Source: Jim Smith

Samuel Robert Henderson was a 17 year old from the Orkney Islands of Scotland when he arrived in the Red River Colony in Manitoba to work for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 1807. By 1826, Henderson had married Flora Livingstone (a relation of famed British explorer and missionary David Livingstone), became a father and was ready to settle into family life. Flora had arrived in the colony with the second party of Selkirk Settlers, and would go on to have ten children with Henderson. Henderson retired from the HBC, which in turn granted him a 100 acres to settle on as per the HBC’s arrangement with Lord Selkirk for retired servants. It was an inauspicious year to start farming along the Red River, which experienced its largest spring flood in the settlements history, many times bigger than the “Flood of the Century” that took place in 1997.

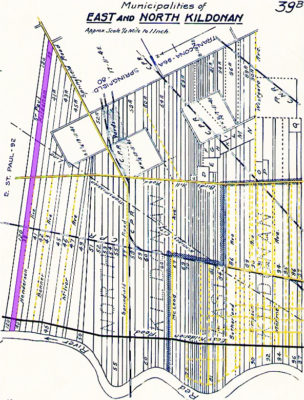

Undeterred, Henderson settled on land on the west side of the Red River, in the modern day Seven Oaks area, where many of the Selkirk Settlers had established themselves. In just over 20 years of farming, Henderson became one of the wealthiest in the area, boasting a house, three stables and a barn along with numerous livestock. His success on this lot makes it all the more perplexing as to why in 1854 he uprooted his family and moved across the river to the mostly uninhabited east shore. What mysterious forces were driving this decision? One might think that the devastating flood of 1852 drove Henderson to seek out higher land, but the east side of the Red River had not been spared by the flooding. Was it an urge to take on a new challenge, expand further than the bounds of the already settled west bank would allow? But in his mid 60s, Henderson was no longer a young man full of youthful vigor and ready to take on the world. Perhaps Henderson was simply tired of the world, seeking a quite place to spend his final years in solitude. Whatever the reason, his new river lot on the east bank of the Red River would eventually be numbered 39 in the Municipality of Kildonan, just inside the modern boundary of the City of Winnipeg.

Henderson House was built near the Red River on Lot 39 (highlighted in purple) in North Kildonan, right along the boundary with East St. Paul.

Source: Archives of Manitoba

On their new lot granted by Lord Selkirk, the Henderson’s first built a little log cabin, which they named “Lord Selkirk Place”. With ten children it would have been rather cozy, so it is not surprising that it was eventually be replaced by a larger house built in the Red River frame style. There are conflicting accounts as to when the house was built, with dates ranging from 1826 to 1873. Erected long before building permits were in use, dendrocronology, the use of tree rings to determine the year a tree was felled, would be the best way to accurately date they structure, but this is unlikely to happen. The earliest date corresponds with Henderson’s retirement and subsequent land grant on the west side of the river, so it could be the result of Henderson’s first house being mistaken for his later house on the east side of the river. Other early dates also seem unlikely as the major flood of 1952, which was almost as bad as the 1826 flood, would have likely washed away any earlier buildings. There are written records placing the Hendersons on the east side of the river in 1854, but it is hard to say if the family built their new house the same year they moved. Grandchildren of Henderson date the house’s construction back to 1873, but this would have the house being constructed almost ten years after the death of Henderson and at a time when the Red River frame style was falling out of fashion, making it unlikely to be correct. A best guess would date the house to the second half of the 1850s, giving the Hendersons sufficient time to move across the river, get the lay of the land and undertake construction. Whatever the exact year it was built, it is indisputable that the house is exceptionally old for the City of Winnipeg.

The Red River frame style was the popular choice for settlers’ homes in the Red River Colony. The building technology was brought from Quebec by the HCB, where the original French pièce-sur-pièce technique was the inspiration. Influenced by the Georgian style of architecture, Red River frame houses were simple, symmetrical buildings with a rectangular floor plan, small windows and a gable or hipped roof. They featured distinctive squared off log construction, with horizontal logs being stacked between vertical uprights. This style of architecture was a good fit for the prairies, where small timber was locally available. The Red River frame style was used for about 50 years, falling out of favour in the 1870s. Manitoba became a province in 1870, which was followed by the arrival of the transcontinental railway in 1881, bringing with it an influx of immigrants with their own building styles. The economy boomed with stone quarries, brickyards and sawmills opening, further contributing to the rise of new and refined styles of architecture and the end of Red River frame. As there had never been a vast number of Red River frame houses in Winnipeg and most were built on desirable river front property that was redeveloped, very few have survived the past century and a half.

Lord Selkirk Place was renamed Henderson House in 1928, residing at 2112 Henderson Highway, where the highway intersects with Knowles Avenue, which was known as Henderson Avenue until 1963. Surprisingly, neither of the streets were named after Henderson! The highway named after the Henderson’s grandson, another Samuel Robert Henderson, a local politician and the first president of the Manitoba Goods Roads Association while the avenue was named after an unrelated Henderson family. Designed to face the river, Henderson House stood a storey and a half tall, built of hand hewn logs and chinked with clay from the riverbank. The addition of a kitchen around 1900 made for a total of nine rooms in the house. The living room was wrapped in tall wainscoting and one inch wide boards were used to finish the ceiling, creating a picture perfect middle class settler’s home. It must have felt like a mansion to the Henderson family after living in the log cabin described as a hut!

Unfortunately, Henderson did not get to enjoy his new home for many years. The 4th of July in 1864 was remembered as a hot day, with nothing out of the ordinary happening when Henderson went outside to tend to his cows. What transpired next is unknown, but Henderson was never seen again, alive or deceased. The man who seemed to be purposely moving farther and farther away from the world left it for once and for all, though if it was by choice, accident or force we shall never know. A tombstone was erected in his memory in the Kildonan Presbyterian Cemetery, next to the church he had help dig the foundation for.

After the passing of Henderson the family remained in the house, with their youngest child, John, being the last of the family to live in the home. A farmer, importer, local politician and school board trustee, John Henderson married Ann Munroe in 1869 and fathered five children. Both John Henderson Junior High School and Henderson Library in Winnipeg are named after him. John retired from farming in 1905 and built a new house at 606 Henderson Highway in 1906, but sources indicate he retained ownership of Henderson House.

The next known inhabitants of Henderson House were Bartel and Martje Hoving, Dutch immigrants who came to Canada in 1911. The Hovings moved into the house in 1926, seeming to have first rented it and later purchased the property. Having only four children the home would have seemed rather empty compared to when the Henderson’s had lived there, especially with the later addition of the kitchen. Like the Hendersons, the Hovings farmed on the property around the house, supporting themselves as market gardeners. Their three daughters, Martha, Dean and Mary, would marry and move away but their son Peter stayed and helped with the family business. The Hovings left Henderson House in 1954, but they did not go far, building a new house along Henderson Highway just in front of the old Henderson House. Peter would go on to marry Marion Baird, have a daughter, Elizabeth, and continued farming on the property well into his old age.

After the Hovings sold Henderson House in 1954, it was lived in until 1976. The area around the house was being developed in the 1970s and the the final owner of the house, Jack Seitz, wanted a piece of the action. But his request to subdivide his property was denied, so he instead decided to build one large new house. A shrewd businessman, Seitz offered the historic house to the City of Winnipeg in 1977 in return for a tax credit, instead of just demolishing it. Looking at pictures of Henderson House from the 1970s, it is not surprising that the Manitoba Historic Sites Advisory Board believed the house was not worth saving as it had been too altered. Faux brick siding and later addition makes the Red River frame building unrecognizable on the exterior, with changes having also been made to the interior. But Seitz suggested some further investigation, which resulted in the original house being found intact under the cosmetic alterations. In much better shape than other Red River frame houses of the same era, the building was “heralded as one of the oldest and most historically significant buildings Manitoba” (Winnipeg Free Press , April 26, 1978, page 159).

Henderson House in 1978, with the lean-to addition on the right most likely being the 1900s kitchen and the addition on the left with white siding being much later.

Source: Jim Smith

Inside Henderson House in 1978, where the finishes were removed to reveal the original structure was still intact.

Source: Jim Smith

While it was easy to agree that the historic house should be saved, going about saving it was another matter. Where the house would go, who would pay for the costs and how Seitz would be compensated all caused the rescue effort to drag on for years. Over time Seitz was growing impatient, demanding the issue be resolved or he would demolish the house. Seitz wanted a $5000 credit applied to his income tax for the next 11 years, $16,000 to cover the costs of maintaining the house during the delay and for the hassle caused by people visiting the house, the basement of the house to be demolished and filled in, and acknowledgement of his generous donation of the house. With the historic house being hard to place a value on, Seitz finally settled for a $2,200 credit towards his income tax and the city demolishing the old basement and fixing any damage done to the yard while moving the house. The city officially accepted the donation of Henderson House on May 3rd, 1978.

The acceptance of a donation of what has been heralded as one of the oldest and most historically significant buildings Manitoba was recommend for city council approval by Winnipeg’s civic parks and recreation committee…Councillors unanimously applauded the project during the meeting, saying it represent a budding and long-overdue awareness of the city’s historical identity… While acknowledging the restoration by the provincial government of the historic Riel and Turenne houses in St. Norbert, Coun. Joe Zuken (Labor Election Committee – Norquay) commented he was “very much afraid the Henderson house will be much older before they make their decision to contribute” towards its costs.

-Winnipeg Free Press , April 26, 1978, page 159

The City of Winnipeg originally planned to move Henderson House about 600 meters south to 1940 Henderson Highway. This was the location of Ross House, the 1922 home of politician Donald Ross. The city already owned Ross House and it seemed ideal to have the two historic homes together in a park where the public could visit them. The plan was for the city to spend $10,000 to move the house and the Province would spend $120,000 to $150,000 to restore the house. But Ross House was in the process of becoming home to Special People in Kildonan East (SPIKE), a non profit organization that provides permanent and respite care for community members with physical and intellectual disabilities. City Councillor and then president of SPIKE Harold Piercy rebuked the idea of moving Henderson House next to Ross House, not wanting the public wandering around the grounds and disrupting the residents of SPIKE who where trying to live normal lives.

Fortunately, the province stepped in and saved the day, offering St. Norbert Provincial Heritage Park as a new home for the resilient Henderson House. Established in 1976, the seven hectare park tucked in a corner of land at the junction of the La Salle and Red Rivers was intended to “protect and promote public awareness and appreciation of an area representative of 19th century Métis and French culture” (Province of Manitoba). Although Henderson House did not exactly fit in with the theme of the park, it was a safe place to land for a year or two until it could be returned to North Kildonan. And so in September of 1979, with the additions removed, Henderson House was loaded onto a flatbed truck and spent 15 hours travelling just over 25 kilometres south to its new home.

Henderson House moving to its new home in St. Norbert Heritage Park in September 1979.

Source: Jim Smith

This is where the happy story ends for Henderson House. City Councillor Joe Zuken’s fears that the house would be waiting a long time for the province to commit any funding to its restoration have been proven warranted. Now the owners of the house, the province’s promises of spending over $100,000 to conserve it have demonstrated to be empty. The once pristine house has been left to rot behind bars for over 40 years, with only a weathered wooden sign announcing its name. Two other historic houses in the park, Bohémier and Turenne, have both been beautifully restored and opened to the public. But Henderson House and its neighbour Delorme House have been ignored, locked away and deemed unsafe for anyone to enter. The North East Winnipeg Historical Society has not forgotten Henderson House, with president Jim Smith continuing to draw attention to its plight. The group continues to lobby the provincial government to conserve the house, but are always told there are no funds available. In 2015 they succeeded in convincing the province to do work on part of the roof which was leaking, but a new leak in another area has gone unaddressed. Having the original Henderson family on board to lobby the government could be helpful, but as the name Henderson is quite common in Winnipeg it has been impossible to track them down. After years of neglect it is now estimated the it would cost at least $100,00 to just stabilize the house, never mind conserve it.

Henderson House has become a prime example of demolition by neglect, when an historic structure’s basic maintenance is deferred to the point that it must be torn down in the name of public safety. Time is a cruel mistress, and when coupled with Winnipeg’s harsh weather it will lay waste to the sturdiest of buildings, reducing stone to dust when people turn their backs. The decay of Henderson House is a horrible loss for the community, an irreplaceable piece of the past that was once in ideal condition, ready to be celebrated. What will it take for the province to step up take responsibility? Another Red River frame house, Barber House, was nearly burned to the ground before anything was done to conserve it. What will it take for Henderson House? Does it have to actually collapse before anyone will care? The province should be a leader in the fight against demolition by neglect, demonstrating how basic maintenance can go a long ways in preserving a building until it is ready to be redeveloped and minimizing future restoration costs. It is the financial and environmentally responsible way to conserve our heritage. Instead the province has become a leader in neglect, seemingly hoping that everyone will forget about Henderson House so when it finally falls down the rubble can be cleared away without anyone noticing. Like the man who built it over 150 years ago, it will simply vanish one day, never having said goodbye, leaving a hole in our hearts forever.

Special thanks to Jim Smith for his insights and resource material on Henderson House!

Interested in the heritage of Elmwood, East Kildonan and North Kildonan? Check out the North East Winnipeg Area History!

All three volumes are available to purchase through the North East Winnipeg Historical Society for $20.

Visit their Facebook page for more information!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Acceptance of historic dwelling recommended to city council | Winnipeg Free Press, April 26, 1978, page 159

Bartel Hoving | Winnipeg Tribune, August 22, 1964, page 29

Building Traditions and Types | Heritage Manitoba

City could lose old log building | Steve Pona in the Winnipeg Free Press, July 5, 1978 , page 44

Demolition of historic house forestalled | Winnipeg Free Press, July 19, 1978, page 105

Donald Andrew Ross (1856-1938) | Manitoba Historical Society

Early Red River Homes | Lillian Gibbons in MHS Transactions, Series 3, 1945-46 season

Henderson House (2112 Henderson Highway, Winnipeg) | Manitoba Historical Society

History in Winnipeg Streets | Manitoba Historical Society

Identifying Architectural Styles in Manitoba | Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Citizenship

John Henderson (1841-1922) | Manitoba Historical Society

"Lord Selkirk Place," Lot 39, North Kildonan | Lillian Gibbons in the Winnipeg Tribune, February 22, 1941, page 16

Marion Susan Hoving | Winnipeg Free Press Passages

Memories of 38 years in Henderson house | Winnipeg Free Press, Septembers 11, 1979, page 3

New location sought for Henderson House | July 1979

Owners attaches conditions to donation | April 26, 1978

Peter John Hoving | Cropo Funeral Chapel

Province to restore old Henderson House | July 1979

Province to Restore Old Henderson House | Manitoba Information Services Branch, July 6, 1979

Restoration plan revealed | Winnipeg Free Press, July 7, 1979, page 5

Ross House (1940 Henderson Highway, Winnipeg) | Manitoba Historical Society

Samuel Robert Henderson (c1790-1864) | Manitoba Historical Society

Samuel Robert Henderson (1863-1928) | Manitoba Historical Society

A System Plan for Manitoba's Provincial Parks | Province of Manitoba

What a wonderful story! I just have to point out one spelling mistake. On the fourth line of the first paragraph, the word “who’s” should be “whose”.

Thanks for catching that!