/ Blog

January 27, 2021

Borrowed Buildings: Treating The 1918 Influenza Epidemic

Influenza came to Winnipeg by train.

On September 30th, 1918, a train of returned soldiers arrived in Winnipeg carrying three men infected with the “Spanish Flu”. City officials, aware of the risks influenza posed, were quick to act and the three soldiers were whisked away to an isolated convalescent home. Still, the damage had been done. By October 3rd, two of the men were dead and the first civilian death had been reported.

Despite what the name suggests, the “Spanish Flu” was not Spanish in origin. The disease is a particularly deadly strain of influenza that originated in Europe in 1917 and began to spread through the soldiers stationed in the trenches during the First World War. Unhygienic conditions and close quarters made it an ideal starting point for a new disease. Spain was not involved in the war, and thus not subject to the same wartime censorship as other countries. The press, then, could report freely the effects of the epidemic in Spain and the “Spanish Flu” moniker was coined. The Spanish coined it the “French Flu” as they believed it came from France.

By the time the disease reached Winnipeg in late 1918, stories of its high mortality rate were well known. The average annual flu, generally, kills mostly the very young, the very old, and those with compromised immune systems. In the case of the Spanish Flu, there was a much higher mortality rate for young adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of pandemic influenza deaths in the United States occurred in people under 65, and nearly half of deaths were in young adults, 20 to 40 years old.

Despite the knowledge of the dangers the disease posed, the City of Winnipeg quickly found itself overwhelmed with rising cases, having to use all manner of buildings to manage and treat the sick.

The convalescent home which the first influenza victims were whisked away to was the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) Home at the Tuxedo Military Hospital. The IODE, a women’s charitable organization, opened five branches in Manitoba in 1909 and provided a variety of services to Canadian veterans. This included establishing a 20 bed cottage at the Ninette Sanitarium, and the creation of a convalescent home in Winnipeg at the corner of Broadway and Donald Street in 1915. They also provided nursing care at the Tuxedo Military Hospital, at 123 Doncaster Street. For civilians who fell ill, their homes would be promptly quarantined and marked by a sign. At the time there was no known easy treatment to the Spanish Flu. Antibiotics had yet to be discovered, so complications such as pneumonia posed a serious (and often fatal) risk. Once you were sick, you were advised to stay home, stay warm, and drink plenty of fluids and wait.

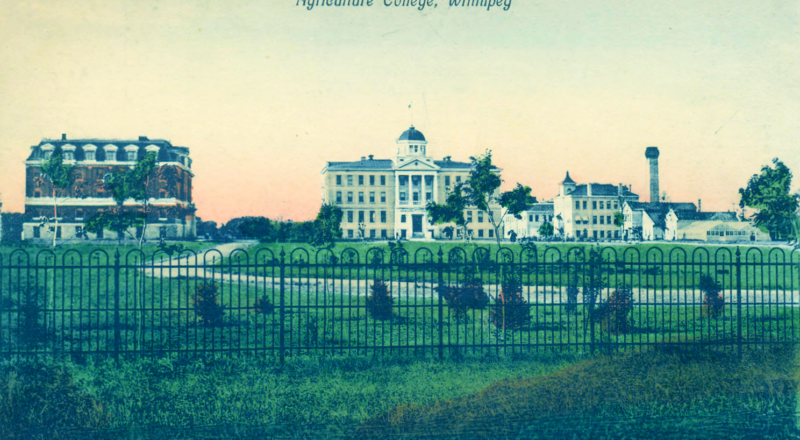

The Agricultural College at 123 Doncaster Street in 1906. It would later become part of the Fort Osborne Barracks and would help treat influenza patients in 1918.

Source: Robert McInnes Postcard Collection

By October 12th, just over two weeks after the first cases were reported, the City of Winnipeg issued a ban on public gatherings which led to the closure of pools and dance halls, theatres, churches, lodges, and public meetings. Authorities were also permitted to order the isolation of infected persons, and to enforce the disinfection or destruction of infected items such as bedding. A few days later, Winnipeg would report 79 cases.

Even with the public health orders, cases continue to rise – and hospitals quickly found themselves strained. A number of Winnipeg hospitals admitted Spanish Flu patients, among them King George Hospital, the Winnipeg General Hospital, the St. Boniface Hospital, Grace Hospital and Victoria Hospital. As cases rose, additional hospitals opened up beds for patients including the North Winnipeg Hospital (known earlier as the People’s Dispensary) and the Children’s Hospital on Aberdeen Avenue. In the first few weeks, cases rose steadily but hospitals stayed quiet. By the end of October, there were nearly a hundred new cases reported each day.

Upper left: King George Hospital (Robert McInnes Postcard Collection)

Upper right: Winnipeg General Hospital (University of Manitoba Faculty of Medicine)

Bottom left: St. Boniface Hospital (Robert McInnes Postcard Collection)

Bottom right: Grace Hospital (Robert McInnes Postcard Collection)

As hospital beds began to fill up, emergency provisions had to be made. This was not the first time the City of Winnipeg had relied on temporary facilities to deal with a disease outbreak (notably, in 1910, an old building at the Exhibition Grounds was used to house scarlet fever victims), and borrowing buildings had become widespread during the First World War to help convalescing soldiers. St. John’s College became a temporary hospital, as did the La Salle Hotel (346 Nairn Avenue) in Elmwood. One of the larger buildings co-opted for influenza treatment was the Old Coffee House, which once sat on the corner of Main Street and Logan Avenue. Two hundred beds were opened in the Old Coffee House, which became known as the Logan Annex. Poor ventilation and overcrowding made work difficult for healthcare workers. The Old Coffee House was likely one of the hardest buildings to work in. It was a three story building with no elevator and a dumb waiter that could be almost impossible to move. The City of Winnipeg reallocated funds from a crematory operating account and hospital funds, to upgrade the Old Coffee House and to create two smaller emergency hospitals in the North End.

Volunteer nurses were called upon to help tend to the sick, at both of Winnipeg’s major hospitals and at their makeshift ones. Over 650 women answered the call (nursing, at the time, was a predominantly female occupation). The job was both physically and emotionally demanding, not to mention dangerous. More than one third of Winnipeg General Hospital’s nursing staff, and twenty percent of its nursing students, contracted influenza while on the job.

Other nurses were required to provide community support. The majority of influenza patients did not visit hospitals, and instead remained in their own homes. This could provide its own unique complications, especially for those living in cramped housing in Winnipeg’s poorer neighbourhoods. Many homes in Winnipeg’s North End lacked bath tubs, and some were shared by multiple families. Some only owned one set of linens, or one outfit, so frequent sanitization was difficult if not outright impossible. And, if one influenza case was reported, the entire family was expected to isolate – meaning simple errands like grocery shopping were off the table.

The Margaret Scott Nursing Mission performed nearly 2,000 home visits throughout the epidemic, assisted by thirty to forty volunteer doctors. Another organization, the Emergency Nursing Bureau, operated food distribution centres across the city. These Emergency Diet Kitchens prepared and sent out meals to flu stricken homes. Most of the supplies were donated, and those that were able were expected to pay for the meals. For those that could not, meals were delivered free. Meals often consisted of some variation of custards, soups, bread and pressed chicken.

The primary location for the Emergency Diet Kitchen was the now-demolished Alexandra School on Edmonton Street, which was demolished in 1969. Due to high demand, a second kitchen was opened at the Broadway Methodist Church and the Grace Methodist Church. The Emergency Diet Kitchen served 500 people on a single day in early November, and continued to feed high numbers of people throughout the month.

The end of the November marked the end of the first, and worst, wave of the epidemic. Public restrictions ended on November 27th and Winnipeggers, eager for a taste of normal life, flocked back to theatres and meeting halls. Diet kitchens continued to operate as the fall wave of influenza did not subside until February of 1919.

It did, eventually, subside. The death toll worldwide was somewhere between 20-50 million, and in Winnipeg there were just over 1,000 deaths. Due to the amount of cases treated at home, it is likely the number is actually higher.

As the pandemic waned and ebbed, life in Winnipeg returned to normal. The dead were mourned, and buried, and missed. Theatres, now reopened, brought new and exciting performances to an audience desperate for entertainment. Diet kitchens were closed, and volunteer nurses returned to other occupations. And Winnipeg’s buildings, from homes and coffee houses turned into hospices, or schools to soup kitchens, were reverted back to their original usage.

Special thanks to Jim Smith, President and Historian/Archivist North East Winnipeg Historical Society, for his help with the research material!

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Sabrina Janke on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Research by Jim Smith

Military Maneuvers: Remembering the Fort Osborne Barracks

Hospital Histories: The Winnipeg Municipal Hospital

Influenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg By Esyllt W. Jones

No Room at the Inn: Death and Burial in Winnipeg, Defining Moments Canada

The Great Pandemic, Wave Magazine

Influenza, Manitoba Historical Society