/ Blog

August 7, 2019

The Making of a Memorable Millennium: The Canadian Bank of Commerce

Grandiose is the word that best describes the Canadian Bank of Commerce, now known as the Millennium Center. Although it rises only six storeys above the sidewalk, a person standing in front of the building cannot help but feel its dominating presence. An early 20th century bank reborn as a 21st century event space, it is a monument to the power of the people who refused to let their heritage be demolished. Having been a bank for nearly six decades before a tumultuous transition into an event space, those entrusted with its care are looking to build on what started as a millennium project, rejuvenating the heritage building through adaptive reuse to ensure its viability of the next 100 years.

Canadian Bank of Commerce at 389 Main Street in 1913 or 1914.

Source: Martin Berman Postcard Collection (public domain via Winnipeg Public Library)

By 1883, only a decade after Winnipeg was incorporated as a city, “Bankers’ Row” had been firmly established on the east side of Main Street, just north of Portage Avenue. It has been suggested that the east side of Main Street was preferable as it was the same side as the post office, therefore minimizing the number of trips that needed to be taken across the notoriously muddy Main Street. Banks from across Canada were opening branches in Winnipeg as the young city prospered, buoyed by the arrival of the new transcontinental railway. Just setting up shop and struggling to survive, many of the banks rented space in preexisting Italianate buildings along Main Street. With dense ornamentation, exaggerated cornices, arched windows and pronounced molding, the flamboyant style of the building was of little concern to the tenants.

The Canadian Bank of Commerce followed this trend, arriving in Winnipeg in 1893. The bank was founded in 1867 by Irish businessman and philanthropist William McMaster, and went on to become the largest bank in Ontario by 1874. Specializing in small scale ventures, President George Cox is credited with the expansion of the bank starting in 1890, both in breadth of portfolio and geography. Initially the bank had been somewhat hesitant to expand westward, as boom and bust cycles in the region made for turbulent investments. Eventually the prospect of riches was too tempting, and eastern customers pushed the bank to take the risk. Considered somewhat of a late arrival in Winnipeg, the bank rented space in the Bannatyne Block, located on the east side of Main Street between McDermot Avenue and Lombard Avenue.

The bank’s new Winnipeg branch quickly found success, outgrowing its rented space in the Bannatyne Block by 1899. The bank’s solution was to buy the building, demolish it and replace it with something larger. But by this time banks were becoming more discerning about their accommodations, no longer satisfied by their initial Italianate rentals. Conscious of their image, banks wanted their buildings to make a statement about their established wealth and success, their trustworthiness and timelessness, all in an effort to attract commercial clients. Banks chose a neoclassical style of architecture to communicate this message to the public, drawing on religious designs from the seemingly golden era of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Money became the new religion, banks the new temples, and bankers the new high priests of finance.

The bank hired architects Darling and Pearson of Toronto, who were helped by local architect Charles H. Wheeler, to design their new building at 389 Main Street. Darling and Pearson, although preeminent architects in Canada, felt no need to break the mold, embracing the popular neoclassical style. They chose a Beaux-Arts approach, embellishing the building with attractive ornamentation. Set back from the street, the building’s blue Amherst sandstone facade featured four tall Corinthian columns supporting a bold inscription reading “THE CANADIAN BANK OF COMMERCE”, capped by a classical pediment. The final product was a predictable, yet elegant addition to the booming young city.

The interior of the building was no less grand than the exterior, outfitted with all the modern amenities, including electric lighting and the most up to date heating system. A large 2000+ square foot banking hall was 26 feet tall, with a marble floor, decorative plaster walls and ceiling, large windows and a mahogany counter with copper grills. Oak mantles, paneling and staircase further embellished the building, with well furnished living quarters for unmarried male staff upstairs, that even included a library.

Winnipeg continued to boom, with more and more banks taking up residence on Bankers’ Row. In 1905 Eaton’s, an iconic Canadian department store, established its Winnipeg store on Portage Avenue. This drew retail stores away from Main Street, leaving more room for new banks, which soon filled up both sides of the street with neoclassical grandeur, from Portage Avenue all the way north to City Hall. The Ontario Bank, Bank of Ottawa, Merchants Bank, Union Bank, Imperial Bank, Bank of Hamilton, Banque d’Hochelaga, Bank of Montreal, Bank of British North America, Molson Bank, Quebec Bank, Dominion Bank, Toronto Bank, Royal Bank, Bank of Nova Scotia, Eastern Townships Bank, Traders Bank and Home Bank all had a branch on Bankers’ Row.

But this second home to the Canadian Bank of Commerce in Winnipeg would not last long. Only eleven years after being built, the bank had outgrown the building. Not wanting to move from its prominent location near the “Wall Street” of Winnipeg (Lombard Avenue), the bank decided to replace the building instead of moving. Surrounding properties were quietly purchased to make room for expansion and the 1899 building was dismantled and shipped to Regina, Saskatchewan.

Architects Darling and Pearson returned to deliver another quintessential neoclassical bank, only larger and more refined, with all the most desirable features of their previous designs, making it their finest example of Beaux-Arts classicism on the prairies. Seemingly based on their 1909 Canadian Bank of Commerce in Montreal, Quebec, the Winnipeg bank had a facade of Stanstead Granite from Quebec, forming eight fluted Doric columns capped by a cornice and decorative baluster, towering 92 feet above the street. Visitors approaching the six storey building were greeted by massive bronze doors, featuring lions heads, classical individuals engaged in banking and exchanging grain, with the words “BANKING” on the north door and “COMMERCE” on the south. Costing approximately $750,000 to build, 2000 cubic yards of concrete and 2 million bricks were used for its construction. It was truly a sight to behold when it opened at 389 Main Street in October of 1912.

The bronze front doors of the 1912 Bank of Commerce in Winnipeg, made even more imposing due to the three steps leading up to them.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

Inside the new bank no expense was spared. Visitors entered the lobby to find themselves surrounded in marble, with a decorative arched plaster ceiling rising 14 feet above the marble floor. Passing through a pair of Doric columns into the 7000+ square foot banking hall, ones attention was immediately drawn 50 feet upwards to the stained glass dome lit by the sky. At 52 feet in diameter, the dome was set between four shields representing the Canadian Bank of Commerce, Great Britain, Canada and Manitoba, surrounded by decorative plaster and supported by 20 fluted Doric columns along the walls. A vast marble floor supported a U shaped marble counter, further embellished with marble columns topped with bronze sculptures. Behind the counter a great vault sat on enormous hinges, all while a five stained glass windows rose up above the 15 foot marble cladding on the lower section of the walls. These windows were mirrored on the opposite side of the banking hall by windows opening up to the second floor of the bank.

The lobby of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The banking hall of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2015.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The banking hall of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, looking towards the entrance in 2015.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The managers office featured an anteroom with eight foot walnut paneling and plaster ceiling, which led into the large main office. The office walls were covered in tapestry and accented in walnut, with a grand walnut fireplace at the north end and crowned with a plaster ceiling and ornate light fixture. On the opposite side of the lobby, across from the managers office, was the savings bank, once again beautifully clad in marble.

The managers office in the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2015.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

Access to the upper floors of the building was by way of a marble staircase or an elevator with a bronze cage. The second floor looked out over the banking hall while the third floor was home to the regional superintendent’s office. Undoubtedly the finest room in the building, it was lavishly decorated with a breath taking gilded plaster ceiling, grand fireplace and quarter-cut oak paneled walls. The fourth and fifth floors were used as office space running along the north, west and south sides of the dome, which resided on the fourth floor, while the sixth floor had washrooms and a caretaker suite. Below the banking hall was the basement, where two vaults, washrooms and lockers were located. Even further below was the sub basement, with the building’s mechanical installations.

The elevator shaft of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The third floor office of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

The third floor office of the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

A building design to stand the test of time and last as long as its counterparts from antiquity, few changes have been made to the building since it was erected by the bank. Mechanical systems have been updated, a roof and artificial lighting installed over the dome and washrooms moved. Yet despite the soundness of the building, in 1968 the bank, which had merged to become the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, decided to leave its flagship location.

With the building empty, plans were made to demolish it, along the with Bank of Hamilton building next door at 395 Main Street, to be replaced with the bane of vibrant cities – a surface parking lot. Fortunately, Winnipegger’s who had suffered through the 1960s and 1970s ideas of urban renewal, which involved demolishing everything to start anew, had had enough. In 1978, people took to the streets in protest of the planned demolition, demanding that Winnipeg’s built heritage be saved. The result of their efforts was the passing of Winnipeg’s first heritage bylaw and the designation of the two banks in November of 1979. This protected the buildings from demolition and prevented the alteration of their character defining elements.

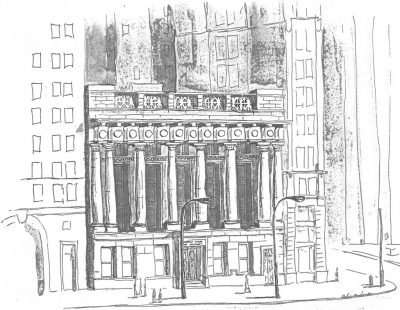

A sketch of the Millennium Centre at 389 Main Street by Robert Sweeney in 2007.

Source: Robert Sweeney (via Heritage Winnipeg)

Though saved, the bank now sat empty, closed to the public, a sad reminder of the bustling financial district that once was. Money was spent on restorations over the years, including restoring the ceiling of the banking hall by Marwest Managment, but no tenants could be found. By 1999 a group of volunteers decided to take action, forming the Winnipeg Millennium Council, with plans to conserve and reopen the building. In 2000, the owners of the bank, coaxed by a generous donation from philanthropist Bill Loewen, kindly donated the building to the 389 Main Street Heritage Corporation, a non profit organization. Work on upgrading and revitalizing the building began in earnest, with the doors opening to the newly renamed Millennium Centre in 2004. A catering company hosting private events in the banking hall provided revenue, critical to the maintenance of the building. Once again, there was life in the grand old bank.

A sketch of the Canadian Bank of Commerce.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg files

Music at the Millennium in the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

Since accepting the responsibility for conserving and revitalizing the bank, 389 Main Street has undertaken numerous projects to ensure the building’s functionality, maintenance and preservation. The mechanicals have been upgraded, plaster repaired in the banking hall, the roof replaced, tapestry conserved and lighting added to the basement. Work will continue in fall 2019, with repointing on the stonework, more plaster repairs and replacing some of the windows. Owning a large heritage building is no small task, as along with regular ongoing maintenance, conservation work must also be done in a sensitive manner to ensure the building’s historical integrity is preserved. Fortunately, through the generosity of the Winnipeg Foundation and the Parks Canada cost sharing program, this invaluable work has been possible.The building is now open for various public events such as Doors Open Winnipeg and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra’s Music at the Millennium, and has been used as the set for numerous films, hosted yoga, pop up restaurants, photographers and more. In 2016 WOW Hospitality became the building’s primary tenant, hosting everything from corporate events to lavish weddings, all while collaborating with Heritage Winnipeg to ensure the building is maintained and preserved.The Canadian Bank of Commerce is a memorable, vibrant, flexible and much loved space, that is widely recognized by Winnipeggers. Moving forward, Heritage Winnipeg is working to redevelop the upper floors of the building, creating a community hub. In partnership with arts and cultural organizations, the building could become a destination in the Exchange District National Historic Site, welcoming Winnipeggers and tourists alike. It is a bank filled with potential, a budding example of how buildings can be successfully revitalized through vision and adaptive reuse, serving its community well into the new millennium.

The Canadian Bank of Commerce, now known as the Millennium Centre, in 2019.

Source: Heritage Winnipeg

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Architectural Styles | Heritage Manitoba

The banks of Montréal: A rich architectural heritage | Richard Burnett - Tourisme Montréal

Beaux Arts Classicism / American Renaissance | Buffalo as an Architectural Museum

Discover the Beauty of Beaux Arts | Jackie Craven - November 10, 2019 - ThoughtCo

The Glorious Parthenon | January 28, 2008 - NOVA

Monuments to Finance: Three Winnipeg Banks | Historical Buildings Committee - City of Winnipeg

Monuments to Finance: Volume II | Historical Buildings Committee - City of Winnipeg

Regina | Architectural Heritage Society of Saskatchewan

Scenes from Regina, Saskatchewan | Scenes from Regina

Step back in history and discover the Parthenon in Greece | North South Travel

Use Them of Lose Them | Kip Park - Construction Manitoba - March 2, 1996

William McMaster | C.M. Johnston - June 4, 2008 - The Canadian Encyclopedia