/ Blog

January 26, 2023

Part One: Sound The Alarm! Winnipeg’s Heritage Is Burning Down

Ever since Winnipeg started building up, fires have been burning the city down. Some fires are small, with the structure quickly rebuilt even grander than before, while some fires are huge, leaving a gap in the streetscape that persists for a century or more. And some fires are tragic, far worse than just a building being lost, people are lost, lives that cannot be replaced. In this winter season, Winnipeg has seen a number of factors converging with destructive and sometimes deadly results. How do we save our heritage buildings from going up in flames? How do we keep our city safe?

One of the worst fires in Winnipeg’s history started on the night of October 11th, 1904 in the basement of the Bulman Block at 218 Bannatyne Avenue. It is suspected that a stray spark from the furnace ignited paper and started the fire, but no one will ever know for sure. In no time, the building, full of highly-flammable chemicals used for the lithography and print business it housed, was a complete loss. But the fire did not stop there – a strong breeze would cause a cascade of disasters. Only 25 minutes after the initial fire had been spotted in the Bulman Block, the flames leapt across Bannatyne Avenue to the Ashdown Hardware Store at 211 Bannatyne Avenue (now the McKim Building), setting it ablaze. Little could be done to dampen this fire as the store was full of kerosene, gun cartridges and gun powder cans, all haphazardly exploding, keeping firefighters at bay.

Chaos erupted as more buildings caught fire, including the Woodbine Hotel at 466 Main Street, a refreshment stand at the corner of Arthur Street and Albert Street, a small Italian restaurant just north of the Ashdown Hardware Store and the Maw Block at 280 William Avenue. People scrambled to gather their belongings and escape the many buildings – including Fire Hall No. 1 at 110 Albert Street – that were threatened by the flames while others joined fire fighters in the battle. Walls began to collapse, shaking the ground as all of Winnipeg seemed to have arrived to gawk in awe at the ever growing inferno. Only lasting about two hours, the fire caused hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage, with four structures (Bulman Block, Ashdown Hardware Store, the refreshment stand and the Italian restaurant) being a complete loss and countless other buildings sustaining damage. Later, Ashdown’s was rebuilt bigger and better, while the Bulman Block sadly became a surface parking lot!

The Ashdown Hardware Store, see here around 1929, was rebuilt so quickly after the October 1904 fire, the first two floors were open for Christmas 1904. The final four storeys were added later in 1905, making the building two storeys tall than the one that burned down.

Source: Province of Manitoba Archives (City of Winnipeg Report)

Although no lives had been lost in the fire itself, later that year 133 people died of typhoid fever from contaminated river water, pumped into Winnipeg’s domestic water system as water pressure was failing during the Bulman Block fire. The lack of high pressure water available had also almost resulted in the tower of Fire Hall No. 1 at 110 Albert Street catching fire as the stream from the hydrant did not have enough strength to reach the top. This would become the catalyst for the construction of the 1906 James Avenue Pumping Station at 109 James Avenue, a world class facility that was capable of pumping over 9000 gallons of water a minute at 300 pounds per square inch. Equipment upgrades for the fire department were also made at this time, as the 1904 fire had demonstrated the existing equipment was simply not sufficient to effectively extinguish such large flames.

Winnipeg’s improved fire fighting infrastructure and equipment worked, with fires becoming less destructive over time. But buildings still burned down, and more lives were lost. The 1922 St. Boniface College fire is thought to be the deadliest fire in Winnipeg’s history, with ten people losing their lives. The 1926 Winnipeg Theatre fire takes the undesirable title of most firefighters lost, when a falling wall killed four of them. The Times Building fire in 1954 saw no lives lost, but is a fierce contender for the worst fire in Winnipeg’s history with the Time Building, Dismorr Block and Edwards Block completely destroyed, and the Affleck Block and Norlyn Building severely damaged.

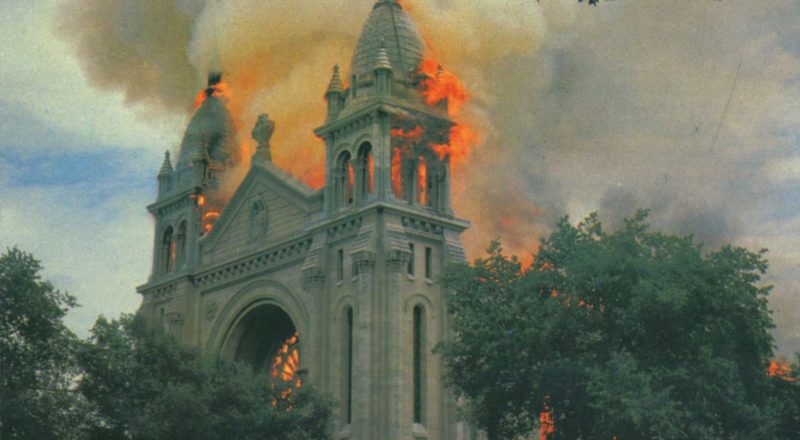

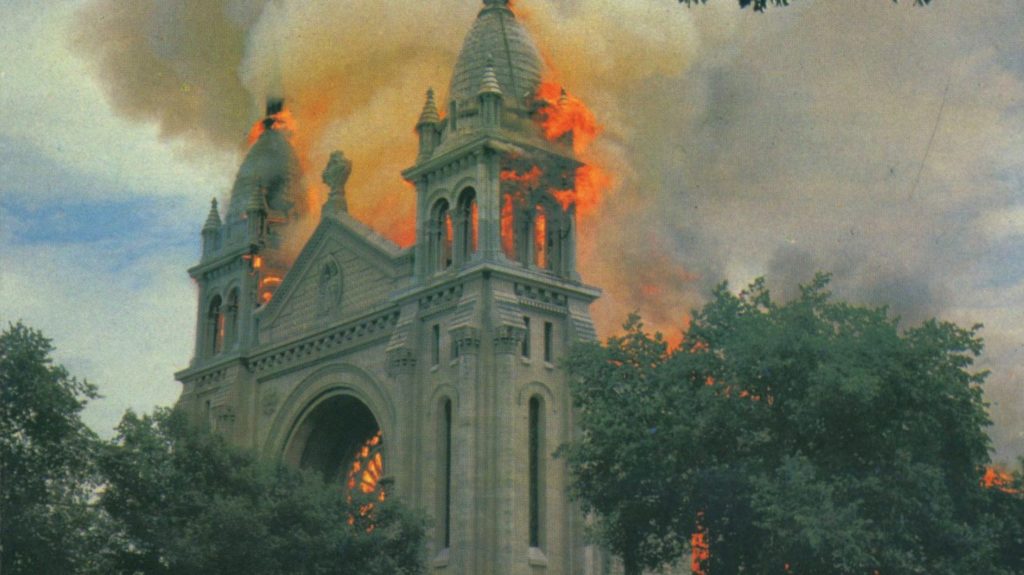

The 1968 St. Boniface Cathedral fire saw one of the grandest buildings in Winnipeg erupt in flames, its towering facade with empty rose window still standing today, keeping the memory of the disaster fresh in the minds of Winnipeggers. The Leland Hotel, an enduring relic from 1884, escaped the wrath of the 1904 Bulman Block fire and was repaired after a 1913 fire, before it was supposed to be demolished by the city at the end of the 20th century. Instead, suspected arsonists beat the wrecking ball to the Leland Hotel, burning down the contentious landmark in 1999.

The list of heritage buildings lost to fire seems nearly unending, with the recent Warwick Apartments (366 Qu’Appelle Avenue) fire caused by suspected arson on December 25th, 2022 resulting in two people losing their lives. Are these tragedies preventable? Why do so many heritage buildings burn down? Why do more fires seem to take place in the winter? Is it just an inevitability that if a building is standing long enough some sort of disaster will befall it? How do we save our built heritage and the people who call it home?

There are many factors that put a building at risk for fire, with some playing a bigger role in heritage buildings than others. First, heritage buildings are old. Parks Canada suggests a building must be 40 years old to be considered heritage, putting structures built as recently as 1983 in the heritage category. This means that heritage buildings were designed to meet safety standards and building codes that are at least 40 years out of date, if not 140 years. While some buildings have been updated over time to improve their safety and conform to modern building codes, it is often the features we cherish the most in heritage buildings and wish to conserve that put them at greatest risk, such as grand, open staircases. Additionally, modern safety measures tend to focus on saving lives, which is undoubtedly most important, but have little regard for saving buildings, meaning even updated heritage buildings can be lost.

Along with their design, the materials used to construct and finish heritage buildings, like timber trusses and wooden flooring, put them at a higher risk of fire. Add to that a century of accumulated dust, oil and people’s stuff, some heritage buildings have a “fire load” that is through the roof. But this should not be misinterpreted as all heritage buildings being a potential death trap. Even a century ago, people were concerned about fire safety and Winnipeg was taking steps to keep its citizens safe. Progressive legislation from 1909 vastly improved the safety of apartment blocks with new building standards, taking what was often considered dangerous, dilapidated housing and elevating it to elegant and desirable homes. As a result, many sturdy, turn of the century apartment blocks are still scattered throughout Winnipeg, safely housing our community.

Winnipeg was also on the cutting edge of many technologies in the early 20th century, becoming an early adopter of steel frame buildings that are less combustible than their wooden counterparts. With this technology, Western Canada’s oldest skyscraper, the Union Bank Building at 504 Main Street, is still standing nearly 120 years after opening. Ironically, even though the timber structures of heritage buildings are combustible, they tend to burn much slower than some of the pressed wood I-beams used in modern construction. The fast burning I-beams end up giving way three times faster in a fire, causing unsuspecting firefighters to crash through the floor to their death.

Another big risk factor for heritage buildings is owners that simply do not install fire prevention and detection equipment. Sometimes seen as ugly and detracting from the beauty of a heritage building, there is the concern that systems such as sprinklers will malfunction, causing tremendous damage and the cost of such systems is always a detriment. And even if a system is installed, it will only save the building if it is functioning well. After the Leland Hotel burned down in 1999, a report noted that the only operational fire alarm in the building was located in the basement, and was far too slow at recognizing and alerting anyone to the fire, which was instead reported by a bus driver. Further compounding the issue, there was no working sprinkler system in the building, making the Leland Hotel doomed the moment the first spark was ignited. Research suggests working sprinklers can control if not extinguish 99% of fires with far less water than a firefighter’s hose and when well maintained, they rarely malfunction. Today sprinklers do not need to be unsightly, while a burned down heritage building is not only very unattractive and completely worthless.

And the list of fire risks facing heritage buildings goes on, although many of them are not exclusive to heritage buildings. From renovations and holidays to arson and vacancy, there are steps that every building owner can take to make their structure safer. Be sure to join us next month for part two of this blog, where we will further discuss the fire risks faced by built heritage but also consider some of the solutions. In a city where a lack of affordable housing is a huge problem, buildings sitting vacant and eventually burning down not only put the community at risk but are a horrible waste of resources. How can Winnipeg use these buildings to ignite vibrant, thriving communities instead of letting problem properties smolder until everything goes down in flames?

St. Boniface Cathedral on fire on July 22nd, 1968.

Source: Past Forward (Winnipeg Public Library)

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Arson Prevention | Red River Mutual

Better alarm, sprinkler system could have saved Leland: report | Keith McArthur - Winnipeg Free Press - April 9, 1999, page A6

Council presses ahead with downtown initiative | David O’Brien - Winnipeg Free Press - May 27, 1999, page A8

Heritage evaluation | Parks Canada - Government of Canada - November 19, 2022

Holidays Most Dangerous Time for House Fires | Enjoli Francis - ABC News - December 20, 2011

How Cities Are Using Innovation To Combat Vacant Properties | GovPilot

Modern homes burn 8 times faster than 50 years ago | CBC News - Sepember 13, 2013

Put A Freeze on Winter Fires | National Fire Protection Association

Reducing Arson at Vacant and Abandoned Buildings | U.S. Fire Administration

Reducing arson risk | London Fire Brigade

Strategies for Vacant and Abandoned Property Reuse | PD&R Edge

Why historic buildings are at risk of burning down | Adam Šapić - Wedding Insurance Group

Winnipeg's 5 Deadliest Fires | Christian Cassidy - West End Dumplings - February 8, 2013