/ Blog

August 21, 2024

Heritage Winnipeg Award Winner: Matthew Jacobi’s Historic Edwardian Home

Each year, at the Annual Preservation Awards, Heritage Winnipeg recognizes the people, organizations and building projects that go above and beyond in the conservation and advancement of Winnipeg’s built heritage. Among the award recipients for residential conservation projects in 2024 was Matthew Jacobi, who restored their 1905 home to its original appearance.

Matthew Jacobi, owner of the historic home at 153 Burrows Ave., accepting a 2024 Annual Preservation Award at the ceremony in April, 2023. Heritage Winnipeg.

While many would assume that a house of that era would be found in areas such as Crescentwood or West Broadway, Jacobi’s historic home sits quite literally on the other side of the tracks; Point Douglas. Technically speaking, the area in which Jacobi’s home at 153 Burrows Avenue is found, is in the neighborhood of North Point Douglas, although it is often labelled under the umbrella of the North End. The home, Burrows House, is not alone in its historic value. The area has many heritage properties, some of which are even designated, such as Luxton School (111 Polson Avenue) and St. John’s Church (250 Cathedral Avenue).

The exterior of 153 Burrows in August, 2024. Heritage Winnipeg.

Before we take a closer look at Burrows House, it is important to explore the history of Point Douglas and the North End in order to gain more context.

A Brief History of Point Douglas and the North End

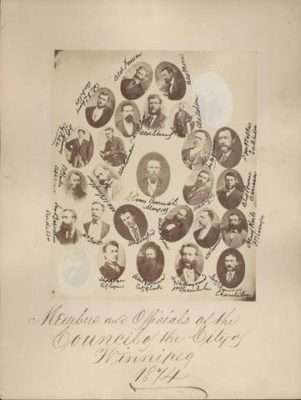

Members and Officials of the Council of the City of Winnipeg, 1874, one of whom was Alderman James Ashdown, seen on the right of the second row from the top. Source: City of Winnipeg Archives, Public Domain.

In Winnipeg’s early days, Point Douglas was filled with houses built for well-to-do families and prominent businessmen. Notably, prominent businessman and politician James H. Ashdown had a home built in Point Douglas for himself and his family in 1877. Point Douglas was chosen as a residential area because of its sufficient distance from the busy commercial area that was growing in what is now the Exchange District, and its proximity to the Red River. Many others followed the Ashdowns, and Point Douglas soon became a bustling neighbourhood.

Postcard image of C.P.R. Yards looking west from overhead bridge, Heritage Winnipeg Collection.

This era was short lived. In 1884, the Canadian Pacific Railroad (CPR) completed their rail yards in the section of land that sat between Point Douglas and the rest of the city. This became a problem for the residents of the area, bothered both by the noise and the inability to easily reach downtown. Those who could afford to, such as the Ashdowns, moved to the quickly developing neighbourhoods in the south end of the city.

The plethora of well-built homes that were left behind by wealthy families did not go to waste. Point Douglas became an affordable living option for immigrant and working class families, and by 1906 the North End contained 43% of the city’s population with only one-third of the geographical area. While Point Douglas’ population grew immensely, the quality of life continued to decline. The proximity to the rail yards made it the perfect place for flour mills, iron manufacturers, saw mills, and other factories that contributed noise and pollution. With only one railway crossing, making the trek into downtown was quite challenging.

The North End market behind Dufferin Avenue and Derby Street, c. 1914. City of Winnipeg Archives, Public Domain.

An additional barrier was that of language. Many of the North End’s residents had immigrated from central and eastern Europe and did not speak English. This made finding work in the city quite difficult, in addition to the racial discrimination they experienced. The alienation and segregation of non-Anglo-Saxon Winnipeggers led to the rise of diasporic communities in Point Douglas. Immigrants began creating spaces in which they could speak their languages, practice their religions, and celebrate their cultures without receiving criticism.

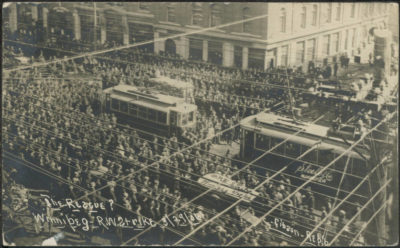

In addition to cultural differences, Point Douglas residents were separated from the rest of their city by their income. The majority of the area’s population were working class; men, women, and children alike working endlessly to make ends meet. This made the ownership of land as well as running for government positions nearly impossible, as alderman positions paid very little for the time that was required. Those who could afford to be in positions of power did not favour the needs of the working class, and this was one of many components that led to the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. Many of the organizers and participants of the strike were North End residents and Point Douglas played a large role in the labour movement.

Photo of crowds gathered around halted streetcars during the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. Source: Martin Berman Postcard Collection accessed via Winnipeg Public Library

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the North End continued to grow as a multicultural community. In the 1950s, members of the Indigenous population began to move into the city from the surrounding areas. Most came with very little, making the North End their new home.

While the North End continues to be characterized by poverty and crime, many community organizations have worked hard to combat the negativity towards the area and celebrate the cultural and historic significance that it holds. Non-profits continue to work towards creating a safe environment through community action and impact, and by providing support for those inflicted by systemic poverty.

Point Douglas’ built heritage has the potential to benefit this cause as well. As seen with the repurposing of the CPR Station in Point Douglas (181 Higgins Ave.) as Neeginan Centre, heritage buildings are often well suited to be adaptively reused as commercial and residential spaces. In these cases, the reuse also serves as a way to conserve the building and preserve its history while conserving the time, energy, and resources needed for demolition and new development.

The historic C.P.R. station at 181 Higgins Avenue, which has been renamed Neeginan Centre. Heritage Winnipeg.

Unfortunately, this is not the case for many of the historic homes in Point Douglas. They are often purchased by landlords who charge egregious rent prices for very small spaces and provide little maintenance, knowing full well that the tenants have few other options. In other cases where they are vacant, they are at risk of fire or they are left to face demolition by neglect.

In the rarest case, someone like Matthew Jacobi comes along and sees the beauty in a historic Point Douglas home.

An Interview and Tea for Two

Earlier this month, Heritage Winnipeg staff had the pleasure of speaking with Jacobi in their historic home at 153 Burrows Avenue. The surrounding neighbourhood was peaceful and picturesque, a stark contrast from the loud and busy atmosphere of nearby Main Street. Homes of various styles and sizes lined the streets, connected by many riverside parks and playgrounds. Geese gathered in a patch of grass that sits at the end of Burrows. The street itself ends in a tight loop, making it one of the quietest strips in the area.

A picturesque path that runs along the river in Point Douglas. Heritage Winnipeg.

Jacobi’s house sits near the middle of that block. While it may blend in at first with the similarly shaped homes at its sides, a closer look reveals a level of careful authenticity that truly honours its Queen Anne Revival roots. An oak door welcomes guests into the enclosed front porch and eyes are drawn to the restored stained glass in the windows on either side of the front door, the painted white brick, and the original wood that makes up the space.

The door to the front porch at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

A rocking chair sits on the porch at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

An oval stained-glass window to the right of the front door at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

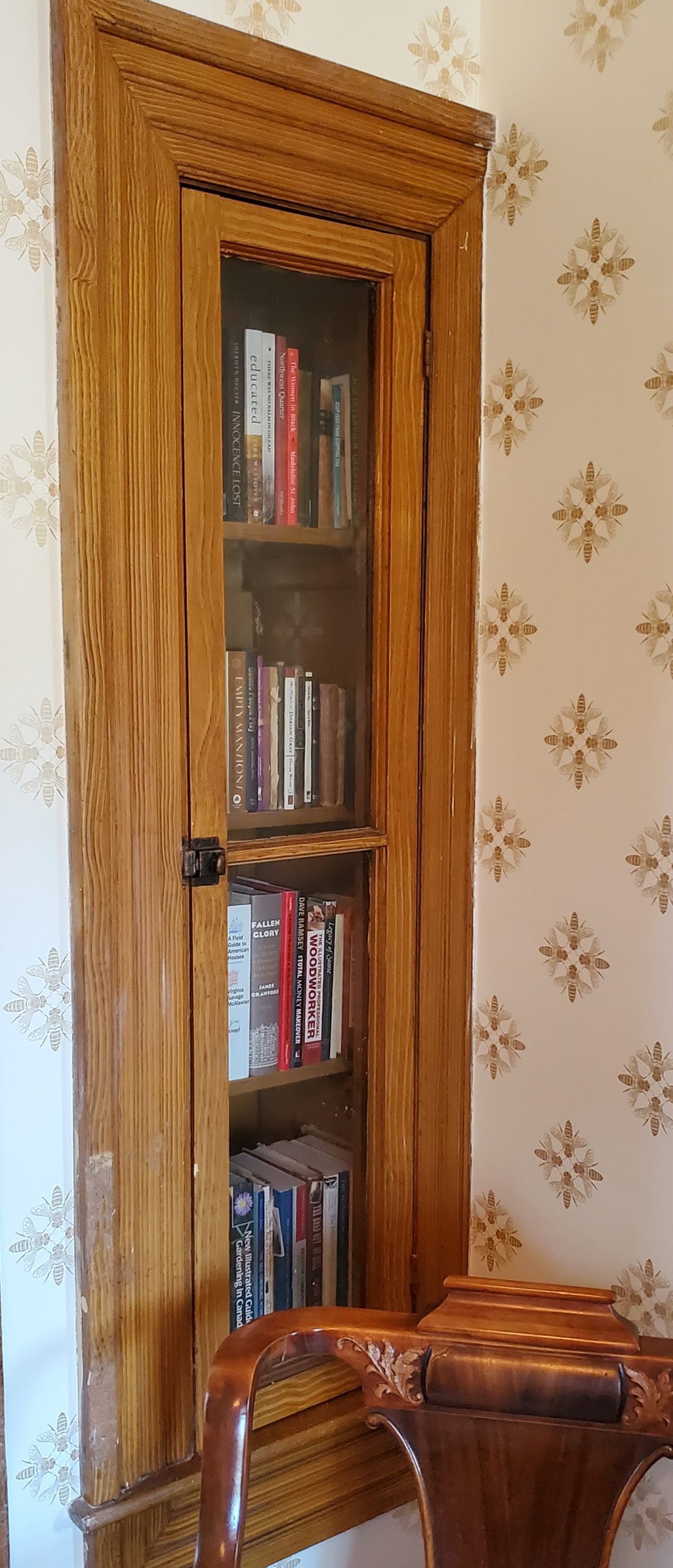

Entering the fully-restored ground floor of the house is somewhat like stepping into an old photograph. The staircase on the right is accompanied by its original bannister and spandrel (the small room below the stairs). The wall on the left holds Jacobi’s 2024 Annual Preservation Award from Heritage Winnipeg. A doorway leads to the front parlour, meant for entertaining guests, and many of the rooms on the first floor have built-in cabinets, used for books and china. Beyond the front parlour is the back parlour, meant for more casual visits. The dining room sits at the end of the hall, with large windows and its original plate rail. A doorway leads to the kitchen, with its original servants staircase and a large pantry where the maid would have eaten dinner.

Jacobi’s 2024 Annual Preservation Award hanging on the wall of 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

Each room is decorated in Edwardian fashion with furniture from this time period, recreating what a middle class, 1905 home in Winnipeg would have felt like. Jacobi’s collection includes a china cabinet with multiple tea sets, a cottage sized piano, an 1850s parlour set, and a 1920s stove, among many other beautiful pieces. Jacobi also re-papered the walls with historically correct reproduction wallpaper.

Reproduction of historically accurate wallpaper at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

Reproduction of historically accurate ceiling paper at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

In the dining room, Jacobi had prepared tea and dainties for the visiting Heritage Winnipeg staff member. The two of them enjoyed a tea service perfectly fit for a historic home as they spoke about its heritage and restoration.

A mid-day tea setting in the dining room of 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

Jacobi purchased the home in December of 2022 and began the larger parts of the project in the summer of 2023, completing the bulk of it during the winter of 2023. Burrows House was not their first restoration project. In fact, Jacobi had restored three homes from different eras before reaching Point Douglas.

“I’ve always been passionate about heritage preservation and restoration. This is my fourth restoration project on a residential home. I really developed and realized my passion, I suppose, through a Victorian Italianate house that my grandparents owned in Moosomin, Saskatchewan, where I was born and raised. I just remember being awe-struck by the hinges, and the doorknobs, and the stained glass, and all the detail. So, I started by restoring and working on that house and it got to a point where it was fully restored back to its original 1894 appearance. I restored another 1920’s home in Moosomin as well, and then upon moving to Winnipeg I found a beautiful late-craftsman bungalow in North River Heights. I restored that house back to its 1931 appearance, and finally, this house here at 153 Burrows, 1905 Queen Anne. I’ve been able to restore this house almost fully back to its original appearance as well.”

A framed professional drawing of the first home Jacobi restored in Moosomin, SK, hanging on the wall of 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

While many would associate Winnipeg heritage homes with areas such as Armstrong’s Point and Crescentwood, Jacobi’s search for his next project led them to the North End.

“I was really looking for a house that had a lot of original detail intact, and I find that in some of the areas in the city now, most of the inventory of available homes have been stripped of all character. Especially the service areas, like the kitchen, servant’s quarters, things like that, have been removed, so I had to look in Point Douglas and I started really narrowing down the area, and I found this home, which had its original servant’s quarters, maid’s staircase and woodwork.

“I think [this project]’s important for our local heritage and our local history. I wanted to be able to be a part of preserving it and providing people with an example of what a typical middle-class home in the Edwardian era, 1905, would have been like in Winnipeg.”

In addition to recreating a 1905 Winnipeg home, Jacobi did some background research on the house’s history.

“It was built by a prominent Jewish family and remained in the family until the mid-1950s. The original owner did live his entire life in this home, and he actually passed away in the house in the 1950s. I noticed a newspaper article from 1931 where they were advertising for a maid for this house. Looking through old newspapers I found some write-ups of weddings that were celebrated here, in the home. Lots of interesting details, as any house like this has.”

The family had one live-in servant, the maid, who would have had her own bedroom on the second floor. There are a total of eight bedrooms in the house, five on the second floor and three on the third floor. Is it possible that the excessiveness of the bedrooms was to accommodate for visiting family members?

The maid’s staircase in 153 Burrows Avenue. The staircase leads from the kitchen to the second floor. It is narrow and curved with no handrail, a typical design for servants staircases of the era as staff comfort was a low priority. Heritage Winnipeg.

With as much knowledge about the house’s past as he could gather, Jacobi began work on the restoration. Through their previous experience, they had acquired a list of tradespeople and suppliers required for the job. Jacobi focused on using natural materials for the project, not only for the sake of eco-friendliness, but also for authenticity. Resourcefulness was a key component of the Edwardian era. While contractors and tradespeople came in handy for a large portion of the project, Jacobi completed 50% of the hands-on work himself.

“For this house, all of the main things that need to be replaced on a house were at the end of their lifespan, so I replaced the roof on the house; I replaced the mechanicals, the wiring, the plumbing; all the plaster on the main floor was repaired, and the ceilings were all replaced with gauging plaster again as it would have had; all the floors were sanded and refinished throughout the house; all the exterior wood was stripped down to the original wood, primed with linseed oil primer and linseed oil paint just like it would have had in the beginning; all the soffit boards, fascia boards and ledger board were all replaced with cedar, exactly like it had; all of the third floor dormers were reclad with cedar shingle again, diamond cut cedar shingle; a lot of the windows needed to remade, the sashes were rotted, all of the stained and leaded glass was damaged and broken so it all had to be taken apart piece by piece and re-leaded, rebuilt, and put back into place. That’s a brief summary of my time,” said Jacobi.

Restoration work, like all work, is easier said than done, and Burrows House did not come without its challenges.

“I think the most challenging part of the project was finding someone competent in plastering an entire ceiling, or plastering entire sections of walls. Another thing was actually re-attaching the front porch, because it had actually come away from the building proper, so we had to bolt the porch roof back into the house and level and reattach it, so that was really challenging. It included opening up the inside of the wall and putting bolts all the way through from the outside to the inside.

The front porch of 153 Burrows Avenue, which was falling off of the house when Jacobi took ownership and has since been bolted back on. Heritage Winnipeg.

Jacobi continued “…one of the highlights was seeing all of the new soffit, fascia and ledger board going on the house, because the eavestrough had failed for probably 50 years and had rotted all of those wooden components to a point where it really affected the curb appeal of the house, so seeing brand new wooden components exactly how they were, it was very very rewarding to see that go back on the house.”

The exterior of 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

Once the dirty work was done, Jacobi set out to put the finishing touches on the house.

“I think my favourite part of the process was the wallpaper, as we all get excited about the finishes. Finding period appropriate wallpapers and ceiling paper was really a highlight, as well as the reproduction push-button mother-of-pearl light switches.”

Reproduction push-button light switches with real mother-of-pearl awaiting covers at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

While the exterior and first floor of the house are completely restored, the only restoration work that has been done on the second and third floors is the refinishing of the hardwood floors. Jacobi continues to add to the first floor and hopes to one day reach the upper two levels.

Each room on the first floor is unique in its shape, design and purpose.

“I think my favourite room is the dining room because it has the original plate rail and the original built in china cabinet, as well as beautiful big windows, the maple flooring, and the grass-cloth wallpaper that I had installed really lends itself nicely to the space, and the unusual shaped wall. There’s sort of a curve to the one wall which adds some interest and accommodates the maids staircase on the other side.”

A china cabinet in the dining room of 153 Burrows Avenue, with the homes original plate rail sitting just above it. Heritage Winnipeg.

While living a modern life in a historic home does come with its own challenges, Jacobi finds it to be an exciting and energizing experience.

“When people come to visit, they say that it’s like stepping back in time, or like a museum, or they ask me if everything was like this and if I’ve done anything to the house, like if all the furniture was included with the house, and I find that to be a great compliment. I find that it’s just noticing the reactions from people and being able to share what life was like with people, and give them a taste of that.”

A view of the hallway from the dining room in 153 Burrows Avenue. Heritage Winnipeg.

The Future of Point Douglas’ Heritage Homes

For Winnipeg’s heritage community, it is comforting to see people like Matthew Jacobi taking the initiative to protect our city’s historic homes. For those hoping to pursue similar projects, Jacobi had a few words of advice:

“I think just to stay motivated to the task and really to look at the architectural features of the house that are still existing, look at the character that’s still there, and really enjoy that character and let that motivate you to carry on with the project and really see the beauty that’s in the house already. We really do need to look at these examples of homes that have been restored and really see what can be done, and really encourage others to preserve these homes and buildings, because once they’re lost they cannot be replicated.”

A collection of modern and antique cookbooks in the pantry at 153 Burrows Avenue. Heirtage Winnipeg.

An important aspect of heritage buildings that is often overlooked is their environmental contributions. Homes from this era were built with natural materials and were built to last. Over the past few decades, we have continuously seen these buildings torn down and replaced with new structures that are often poorly constructed. When heritage buildings are lost, we also lose the embodied energy that was needed to construct the building and more energy is spent to build something in its place. Heritage homes in Point Douglas have the potential to be used for affordable housing when they are well maintained, and conserving them helps preserve the community’s history. Projects such as Jacobi’s honour the families and individuals who built a strong community in the North End, despite the neglect and negative treatment they faced. Throughout its peril, Point Douglas has remained a beautiful and significant area. It is part of Heritage Winnipeg’s mandate to work with the community to help ensure that our built heritage is protected and not forgotten.

Thank you Matthew Jacobi for the lovely interview and for inviting Heritage Winnipeg into your beautiful home and allowing us to take photos.

Click through the slides below to see photos of 153 Burrows Avenue before and after the restoration project.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

Gibbons, Lillian. Stories Houses Tell, Hyperion Press, 1978.