/ Blog

May 1, 2020

Victoria Hall: Finding a Piece of The Past

Victoria Hall, a theatre dating from the late 1800s, created a much different experience from the ones we know and love today, such as the Park Theatre or Burton Cummings Theatre. Safety features, building materials, and forms of entertainment have all been dramatically changed and upgraded. But one thing has not changed and that is the theatre’s history. A history that has helped pave the way for the future of entertainment and the safety of all those in attendance.

In the late 1800s, Winnipeg’s population was growing at a drastic rate with about 9,000 inhabitants in 1881 tripling in just a decade. As the city grew, so did the need for theatrical entertainment, with more opera houses and theatres gradually opening. Some of the remnants of these theatres can still be (and have been) found in Winnipeg today.

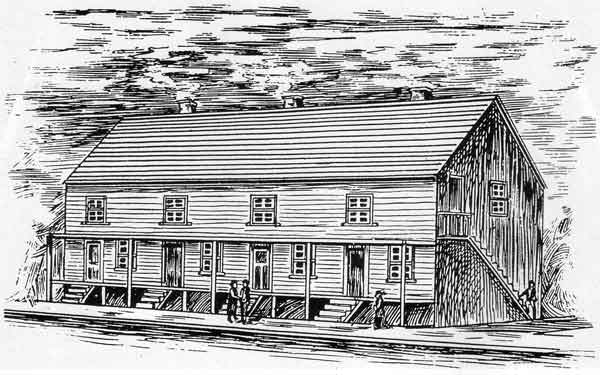

One of Winnipeg’s first recorded forms of theatrical buildings was the Red River Hall. A group of men who were a part of the Red River Settlement created a dramatic society near the end of 1867. The men used the space on the second floor from a pre-existing building that had shops on the main level. It was a small space and the building, made of wood, was unstable. Due to these issues, they instructed people not to clap or stamp their feet in the hall. They added benches, a miniature stage, and oil lamps that they used as footlights. Poles were added to the main floor to keep the unstable second floor from collapsing. But the building was by no means fireproof and in 1874, it caught fire and burnt down.

The Red River Hall (1867).

Source: Archives of Manitoba

While the Red River Hall did not last long, it set the stage for future theatres and opera houses in Winnipeg, like the Theatre Royal (1870), Lower Fort Garry (1870-71), Manitoba Hall (1872), and the Garrison Theatre (1871-72). During this time, these theatres would host comic songs and presentations like The Child of Circumstances at the Theatre Royal, dramas like Barney and the Baron at the Lower Fort Garry, and comedies and farces like The Artful Dodger and Boots at the Swan at the Garrison Theatre.

One of Winnipeg’s earliest purpose-built theatres was Victoria Hall. The hall was built in 1883 by Winnipeg businessman Thomas McCrossan, at a time when Winnipeg’s real estate was booming due to the arrival of the transcontinental railroad the previous year. Located on the western side of the intersection of Notre Dame Avenue and Adelaide Street, it was in the midst of the theatre district, about two blocks from the later Walker Theatre (now known as the Burton Cummings Theatre). Today, the lot is home to the Manitoba Hydro substation called Adelaide Station.

A newspaper clip from the Winnipeg Free Press on July 6, 1883, announces the opening of the Victoria Hall:

Victoria Hall, on Notre Dame street will be formally opened by a grand concert next Tuesday evening on the 10th inst., given by the united choirs of Knox and the Congregational churches, under the leadership of Mr. Hecker.

Shortly after the news, the sacred concert was postponed because of building delays, with the opening rescheduled for Friday the 13th. Perhaps this ominous opening date was a foreshadowing of things to come?

The exterior of the Victoria Hall was made of brick with a wooden interior. Inside the hall had a fine stage with dressing rooms and a box office. A magnificent organ rested on a platform for concert purposes. One of the Victoria Hall’s most memorable characteristics was the drop curtain which would come down at the end of a performance with such a large thud, it caused the entire building to shake!

While the theatre went through plenty of name changes over the years, it would go on to host dances, music shows, concerts, lectures, comedies, and even church congregations for the time it stood.

The first name for the Victoria Hall did not last for long, as it was soon called the Bijou Opera House in 1890 when Confederation Life took over. Bijou translates to “jewel” in French — a fancy name to match the fancy new theatre, which went through a number of renovations at this time. The centre stage of the theatre was raised and the gallery was expanded to fit 800 people.

Times were tough for theatre in the early 1890s due to a declining interest in dramatics. People began to turn to larger theatres with music and more extravagant plays. During this period the Winnipeg Operatic Society resided in the Bijou, with members of the society staging plays and comedies like Merciful Powers and Quits. One of the more well-known plays produced at the Bijou Opera House in 1892 was Romeo and Juliet. The Bijou hosted classics like this as well as many other plays and comedies.

One of many theatres in Winnipeg during the late 1800s was the Princess Opera House, built in 1883 to seated 1,300 people. While the beautiful brick covered wooden structure was seen as one of the finest opera houses, rumours spread about its unsafe design, with people calling it a “death trap.” There was a high risk of fire at the Princess Opera House due to the kerosene lamps and a hot-air furnace used during cold weather. Despite complaints, the building did not add better safety measures and in May 1892, the Princess Opera House met its inevitable fate. The building burned down, taking a whole block of approximately 19 buildings with it.

In 1897, the new manager of the Bijou, Corliss Powers Walker renamed the Bijou Opera House the Winnipeg Theatre and Opera House. It is possible the frequent name changes to the theatre was a part of a marketing or rebranding tactic. With the new name came new renovations which brought in galleries, a stage and dressing rooms — all to create the building as a “modern playhouse.” The expanded theatre could now seat up to 1,000 people in the auditorium on the second floor. Still made of wood, the second floor of the theatre would host all sorts of productions including operas and public lectures on a grand scale, with a variety of shops on the main floor.

Walker was a theatrical impresario, someone who organizes and finances concerts, plays, or operas. An impresario’s role in stage arts is comparable to a film producer today. Walker also developed the iconic Walker Theatre in 1906. The Walker Theatre was announced as the “finest play-house in the Dominion” and “absolutely fireproof.” The theatre had a contemporary design with sixty feet high vaulted ceilings and a decorated interior with silk curtains, murals, velvet carpets, and crystal chandeliers. The theatre hosted university dramas and groups, social and political events, and operas to name a few. The Walker Theatre (now known as the Burton Cummings Theatre) was named after Walker and still stands today in Winnipeg.

While the Walker Theatre was known as one of the safest theatres, the Winnipeg Theatre and Opera House was almost the opposite. The foundation of the Winnipeg Theatre and Opera House was already quite old by the time Walker owned it and many people questioned if the building should still be up. That was not the only issue. With the new renovations to the Winnipeg Theatre and Opera House came new concerns. People were worried about potential fire hazards of the building —particularly the placement of the second floor over the main floor’s variety of shops. At the time theatre fires were a frighteningly common occurrence in the country, with the similarly built Princess Opera Theatre having just been destroyed by fire 1892.

Despite repeated fires, there had been no fire-related theatre deaths in Winnipeg in the early 1900s. But news about the devastating and deadly Iroquois Theater fire that happened in Chicago, Illinois on December 30, 1903, rightly fueled concerns. The five-week-old theatre claimed to be fireproof at the time, yet it would go down in history as the deadliest single-building fire in the United States with just over 600 deaths.

The horrendous death toll was a result of Iroquois Theater not having proper safety measures in place. Reports said that curtains blocked the exits, so people did not know where to go to escape the flames and smoke. Metal gates placed to keep people in the top levels from getting fancier seats on the main floor ended up trapping them in the burning building. Unfamiliar door locks and no ladders to higher exits on the second floor made it near impossible for patrons to flee the raging flames.

After an investigation, the source of the Iroquois Theatre tragedy was found — an oil lamp. The lamp caught a curtain on fire and panic had spread though the people in the theatre as quickly as the fire. Unfortunately, back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, these type of theatre fires were common because of non-fireproof materials being used. Some buildings were made mostly of wood which would quickly catch fire and many did not have proper exits or escape routes either.

After the devastating news about the Iroquois Theatre, cities around the world began upgrading building bylaws to avoid the same events being repeated in the 1900s. In 1926, Winnipeg upgraded the bylaw for theatres, requiring them to add new fire-protection measures such as hose stations, sprinkler systems, and a fire alarm. In January 1927, Winnipeg City Council passed amendments for panic bars on doors that eventually led to today’s emergency exits. Theatre exits had to be properly marked and doors had to be designed to allow people from the inside of the building to push the doors open.

While many of the other major theatres in the area complied, the Winnipeg Theatre had refused to renovate because it claimed it did not host events frequently enough, and as such should not have to comply with the bylaw. The theatre’s wooden structure with a brick veneer failed to meet the requirement of the city’s bylaw that called for buildings to be made of fireproof solid brick or stone. The safety concerns regarding the flame-resistant capability of the older building became reality shortly after when the Winnipeg Theatre tragically caught fire on December 23, 1926.

At 10:00 a.m., the fire department received a call about smoke coming out of the Winnipeg Theatre. The crew from Fire Hall No. 2 was the first to respond followed by firefighters from Fire Hall No. 1. When they arrived on the scene 30 minutes later, reports say the fire was large but manageable. Firefighters pulled out hoses and tried to battle the flames despite the freezing conditions. At one point, a fire truck became encased in ice, showing just how cold the weather the firefighters were working in was.

Overcome by the flames, a part of the theatre’s wall collapsed. Photographer for the Winnipeg Tribune, C. P. Dettloff, caught the moment the theatre wall fell. According to the Manitoba Historical Society, Dettloff said that this photo would be his most powerful:

Although I consider it the best news picture I’ve ever taken, there was no pleasure in it then, nor since.

Four firefighters from Fire Hall No. 2 were killed when the wall collapsed. Arthur Smith, Donald Melville, Robert Stewart, and Robert S. Shearer died that day. December 23, 1926, would be known as the worst fire in the Winnipeg Fire Department’s history.

Speculation about the cause of the Winnipeg Theatre fire led to three investigations: the provincial fire commissioner, a coroner’s inquest, and an operational review by the city. Many argued about who or what was to blame for the fire. Some believe it was the result of a secret party in the basement of the theatre, while others wonder if an oil lamp sparked the flames much like the Chicago fire. However, despite investigations, no one was ever able to fully determine the cause of the Winnipeg Theatre fire.

In the early 1900s, it was common for interior and exterior doors to be locked as a way of keeping non-paying people from entering the building. But this also kept paying people from exiting through these doors in the case of an emergency, trapping them inside. Carl Prinzler, a salesman in Chicago, was supposed to be in the building during the Iroquois Theatre fire, but did not go due to business matters. Along with architectural engineer Henry H. DuPont, he created the panic hardware in Chicago in 1908, allowing people to easily exit buildings during emergencies. The creation led the way for emergency devices and while the panic bar has gone through plenty of alteration over the years, we still use them to this day.

Years later, people have not forgotten the Winnipeg Theatre and Opera House and the events that took place. In 2017, Manitoba Hydro workers excavated the site for a new substation and found remnants (also known as shards) of the foundation and stonework from the building. They thoughtfully donated these shards to Heritage Winnipeg.

The large shard from the theatre provided by Heritage Winnipeg (2017).

Source: Heritage Winnipeg files

Our city was built on thousands of years of history starting with the Indigenous People. Despite the theatre fire tragedies from the late 1800s, finding the shards from Victoria Hall shows us that every time we put a shovel in the ground, we are bound to dig up a piece of the past. Even though fires caused these theatres to burn down, we can be assured that the history of these buildings will live on, whether through remnants we find or through documentation of the past.

Had the excavation workers not realized the importance of these shards, we may have never seen them again. It is possible the shards would be another addition to our landfills instead of being reused as a way to preserve our history. To receive these precious pieces of theatre history to share with the rest of Winnipeg is a wonderfully rare opportunity.

Heritage Winnipeg is currently selling the 135-year-old shard found from the Victoria Theatre excavation site in 2017. The stone shard is about 5 feet long by 2.5 feet wide and weighs roughly 300 pounds. This is a great chance for you to own a valuable piece of history and display it in your home or garden! You could use this shard as a garden bench or a mantel for your fireplace, making your home beautiful all while helping preserve a piece of history!

You can view the listing for the shard here. Heritage Winnipeg also has many smaller shards from the Thomson and Pope Building available —just give us a call at (204) 942-2663! It is incredible to think about how history from over a century ago can live on today and help enrich our lives as a functional and beautiful addition to our homes and gardens.

Special thank you to Greg Agnew (Heritage Winnipeg Board Member) for his insights as a historian about Winnipeg theatre buildings.

THANK YOU TO THE SPONSOR OF THIS BLOG POST:

Written by Georgia Wiebe on behalf of Heritage Winnipeg.

SOURCES:

CBC News | Pieces of 19th-century Winnipeg Theatre dug up last year now for sale on Kijiji

Chicagology | Iroquois Theatre Fire

Chicago Tribune | The Iroquois Theater Fire

Dance bob | Theatres of Winnipeg 1900 to Present

Library and Archives Canada (LAC)| Manitoba (1870)

Manitoba Historical Society | Events in Manitoba History: Winnipeg Theatre Fire (23 December 1926)

Manitoba Historical Society | On Stage: Theatre and Theatres in Early Winnipeg

Smithsonian Magazine | The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever

Statistics Canada | The Census: One hundred years ago

The Canadian Encyclopedia | Music in Winnipeg

Winnipeg Free Press | Fallen firefighters not forgotten

Winnipeg Free Press | Tragic Theatre: Building’s collapse killed four firefighters